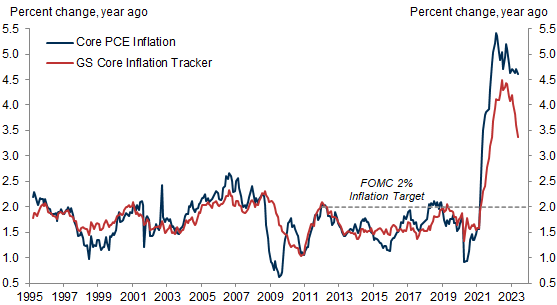

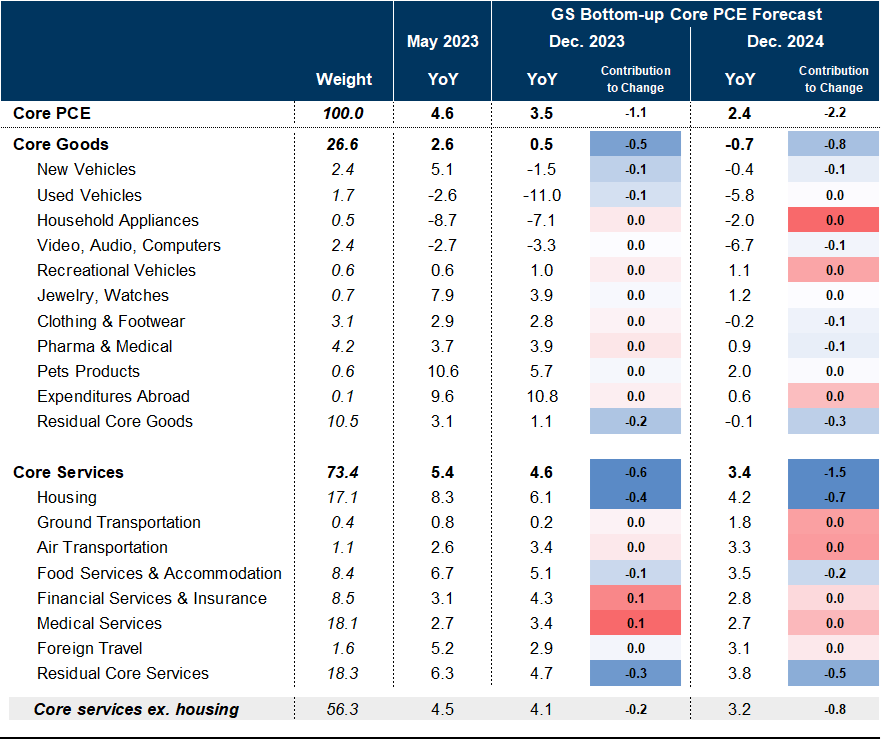

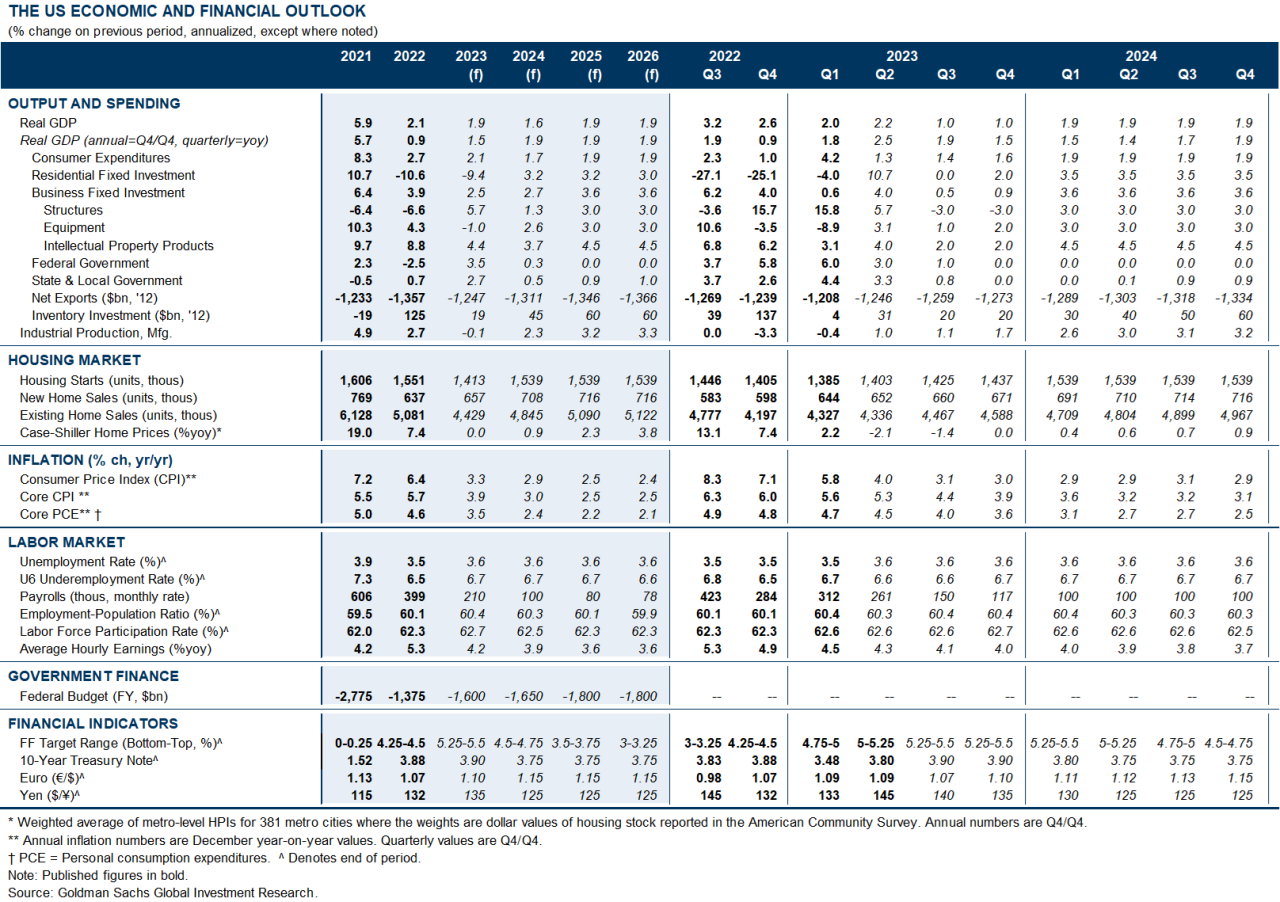

Core inflation stopped falling in the first half of the year, and the FOMC now projects the core PCE measure to end the year at nearly double its 2% target. However, we see four reasons to expect renewed declines in inflation this summer and beyond: 1) the 9% pullback in used car auction prices that we believe is only halfway done, 2) negative residual seasonality in the summer for CPI and PCE prices, 3) the sharp deceleration in apartment rent list prices and diminished upward pressure from lease renewals, and 4) significant progress on labor market rebalancing.

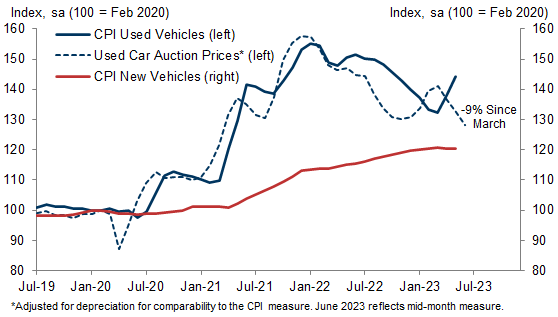

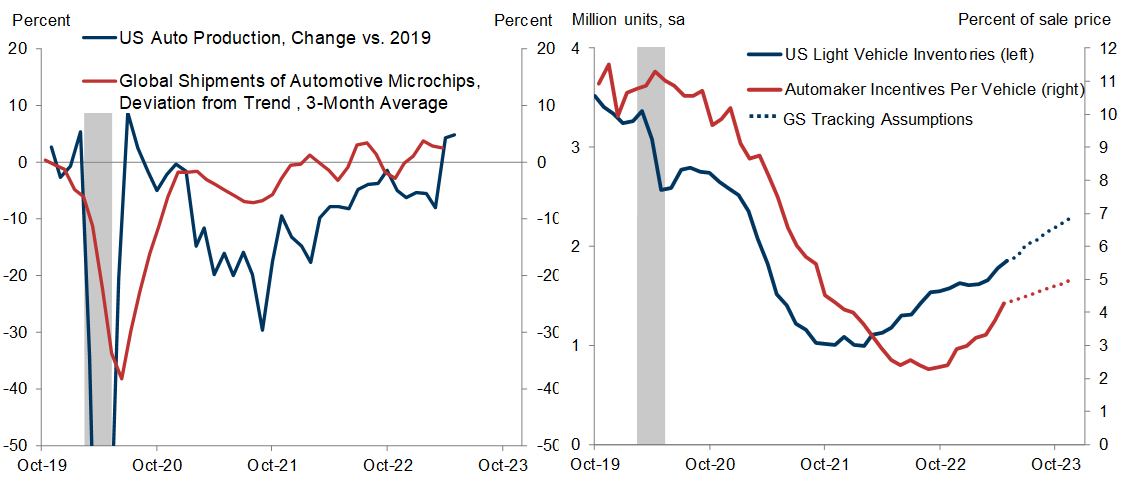

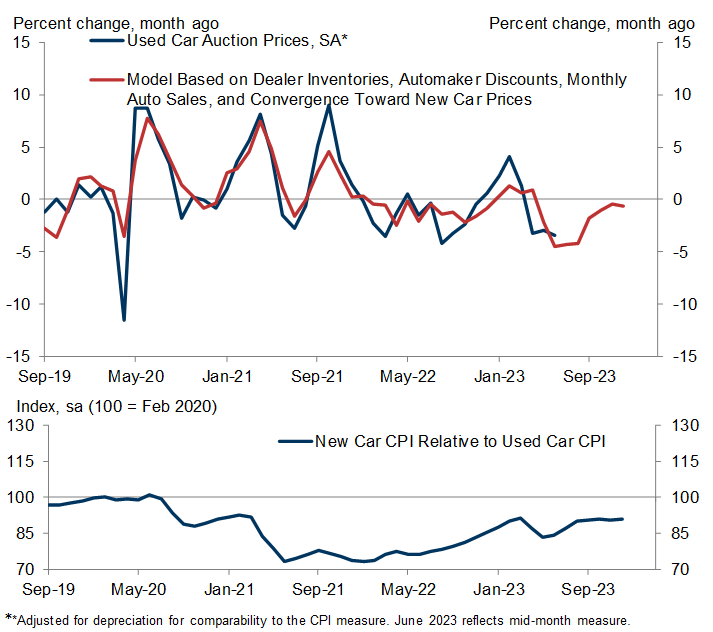

Used car prices surprised to the upside in the first half of the year due to China’s Covid wave and a lull in global microchip production. But looking ahead, the three strongest predictors of used car prices—new vehicle inventories, new vehicle incentives, and the new-versus-used price differential—all point to significant declines. Used car auction prices have already pulled back 9%, and our model suggests another 9% drop this summer and fall. And importantly, these declines will begin flowing through to consumer prices with the June CPI data in two weeks.

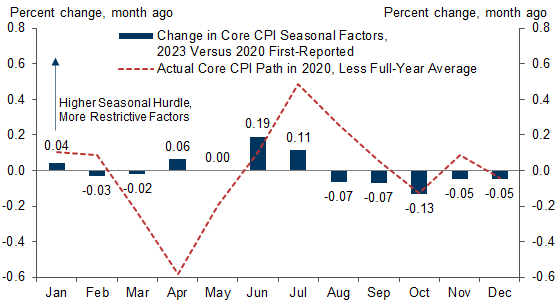

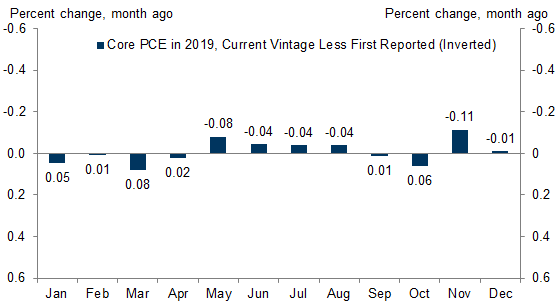

The second reason to expect lower inflation this summer is residual seasonality. We find that both the CPI and PCE seasonal factors are spuriously fitting to the sharp in rebound in travel and transportation categories in mid-2020, following the end of the initial Covid lockdowns. We estimate seasonal headwinds of 10-15bp (mom sa) in both of the next two core CPI readings (June and July) and of 5bp in each of the next three core PCE readings (June, July, and August).[1]

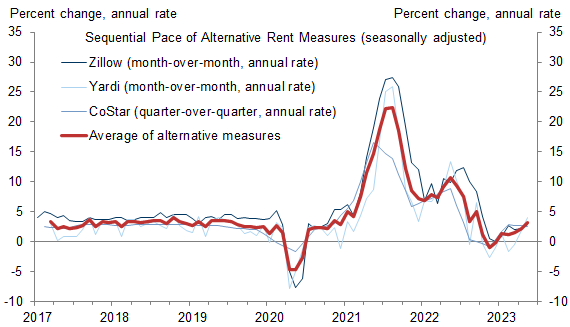

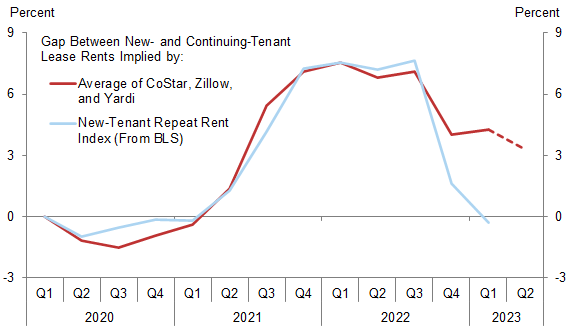

We also continue to expect a further decline in shelter inflation. The best alternative rent measures have slowed from a +20% annualized pace in mid-2021 to just over +1% annualized in last 8 months. Additionally, Cleveland Fed research and our own analysis using alternative rent data reveal that at least half of the post-pandemic premium on new rental units has unwound—which will reduce upward pressure on lease renewals. These findings validate the spring stepdown in monthly shelter inflation and argue for additional slowing in coming quarters.

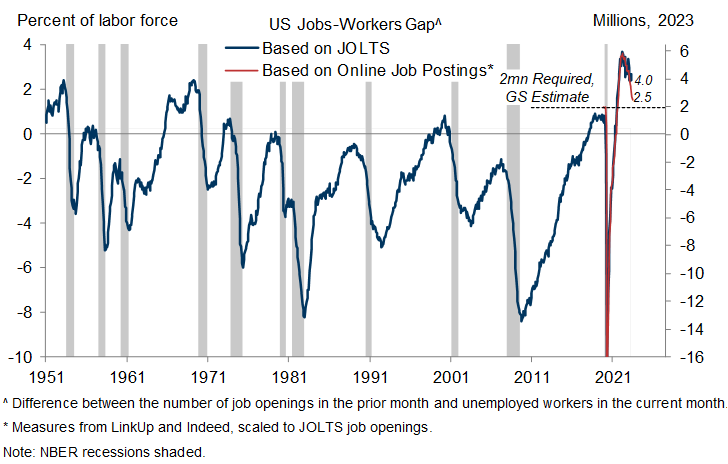

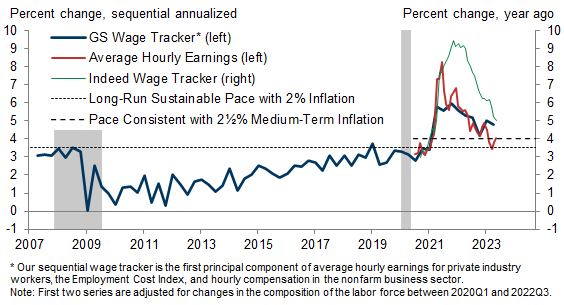

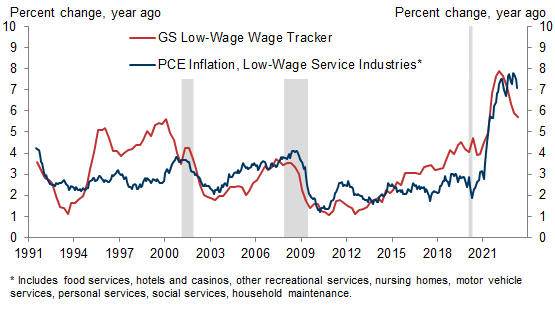

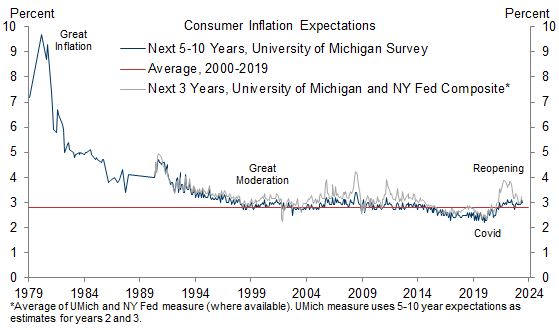

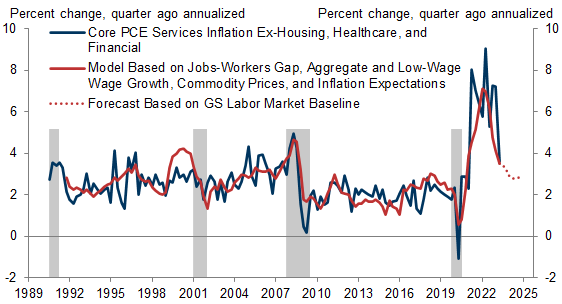

The final reason to expect lower inflation readings is also the most durable: the significant progress on labor market rebalancing. Our jobs-workers gap has roughly halved, and sequential growth in average hourly earnings has already slowed to the 4% pace we believe is necessary to bring medium-term inflation back into the Fed’s comfort zone. The normalization of commodity prices and inflation expectations—both beneficiaries of the more balanced labor market—also argue for a slower pace of inflation. We find that these four variables can explain all of the 2023 pullback in non-housing services inflation excluding the (lagging and idiosyncratic) healthcare and financial services categories—and they argue for further moderation ahead.

We are lowering our December 2023 core PCE inflation forecast by two tenths to 3.5% year-on-year, and we are now assuming a sizable slowdown in June for both core CPI (0.24% vs. 0.44% in May, mom sa) and core PCE (0.21% vs. 0.31%). Such an outcome would validate the Fed's plan of slowing the pace of monetary tightening and would further reduce the odds of back-to-back hikes in July and September, in our view.

The Case for Declining Core Inflation

Renewed Declines in Used Car Prices

Residual Seasonality Headwinds

A Further Gradual Decline in Shelter Inflation

The Fruits of Labor Market Rebalancing

Inflation Outlook and Fed Implications

Spencer Hill

Appendix

- 1 ^ Uncertainty around the magnitude of the PCE price bias is higher, because the BEA statistics can choose whether or not to use the CPI seasonal factors and because their own seasonal adjustment approach (contemporaneous seasonal adjustment) is relatively more likely to revise away some of the residual seasonality with each subsequent year of data.

- 2 ^ The reopening of the Chinese economy also likely contributed.

- 3 ^ We model auction prices as opposed to consumer prices, because the former are source data for the latter, and the latter suffer from issues related to changing methodologies and residual seasonality. We exclude lags of auction prices because we are interested forecasting the multi-quarter path based on the information in hand today.

- 4 ^ We find a smaller role for new car and used car unit sales (demand).

- 5 ^ We also estimate a model that includes the flow of used car supply from expiring leases and rental car company fleet dispositions. This model indicated a more moderate decline in used car auction prices (-12% peak-to-trough in 2023, compared to -18% for our baseline model). However, the coefficient on used car supply is not statistically significant, and we place more weight on the model shown.

- 6 ^ Uncertainty around the magnitude of the PCE price bias is higher, because the BEA statisticians can choose whether or not to use the CPI seasonal factors and because their own seasonal adjustment approach (contemporaneous seasonal adjustment) is more likely to revise away some of the residual seasonality with each subsequent year of data.

- 7 ^ We will update our estimates in the second week of July to reflect the nowcast information set.

- 8 ^ To 4% or slightly below by year-end on a seasonally adjusted sequential basis.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.