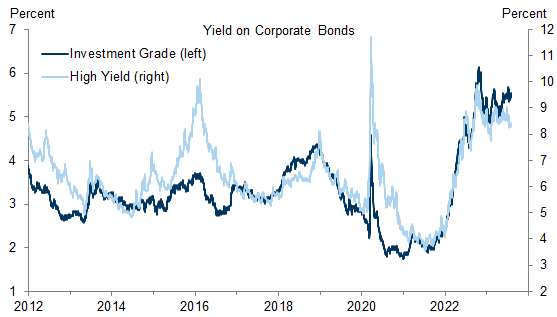

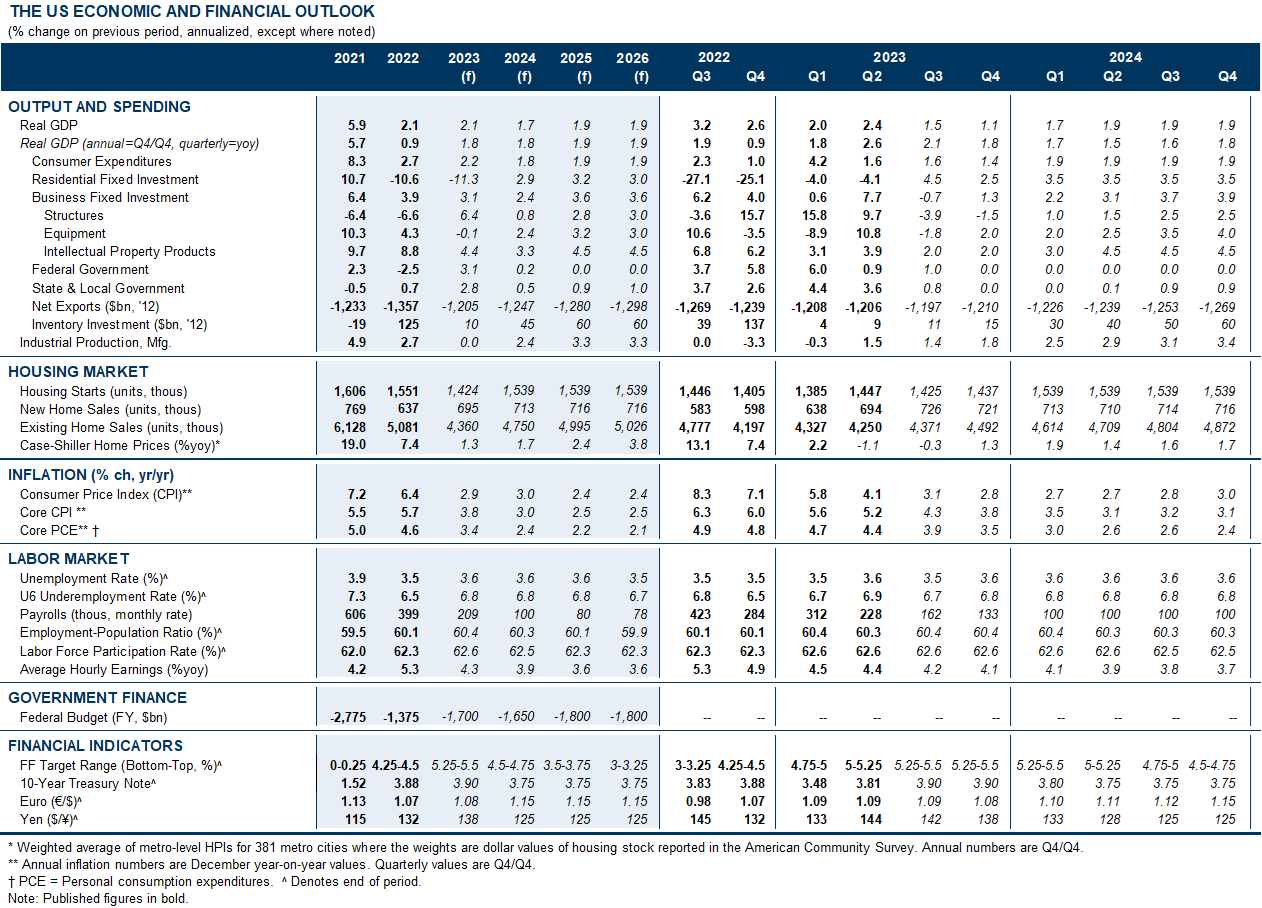

The Fed’s tightening cycle has pushed marginal funding costs for businesses sharply higher over the past couple of years, with yields jumping almost 5pp for high yield bonds. If interest rates remain high, companies will need to devote a greater share of their revenue to cover higher interest expense as they refinance their debt at higher rates. We explore the magnitude of this looming increase in interest expense and the potential impact on capital spending and hiring.

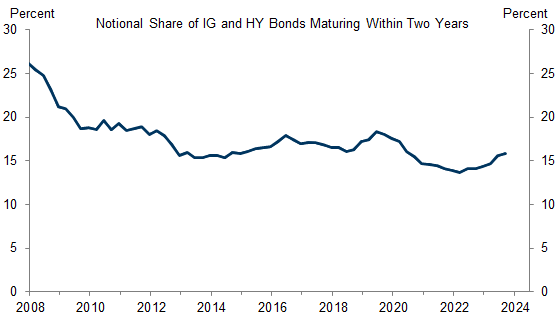

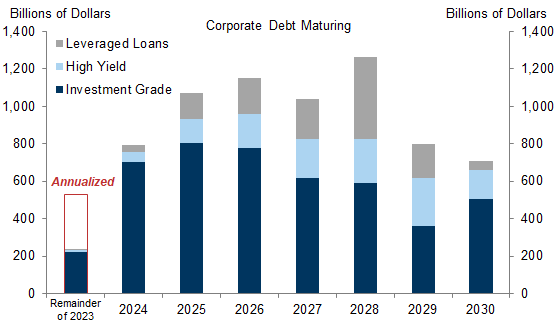

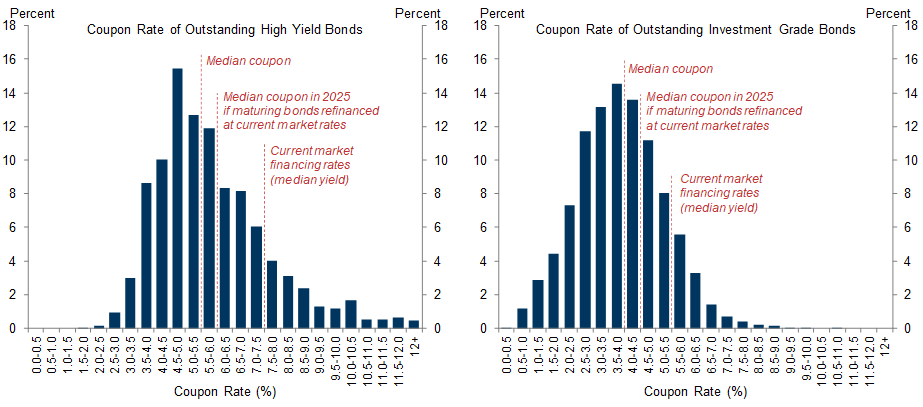

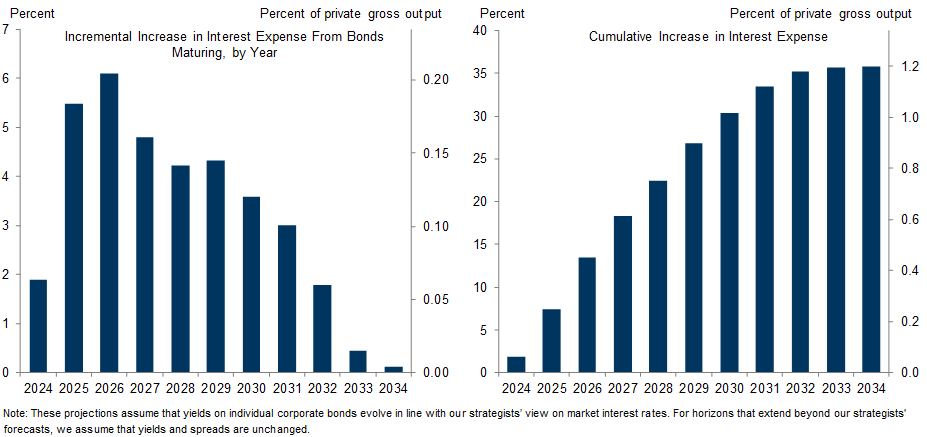

The path for interest expense depends on future refinancing needs and interest rates. Refinancing needs will remain historically low over the next two years—about 16% of corporate debt will mature over the next two years. The interest rate on refinanced corporate debt will increase substantially because current market rates are roughly 1½pp above the average rate that companies are paying on existing investment grade bonds and 2pp above the average rate on high yield bonds.

We estimate that the average interest rate on the current stock of corporate debt will rise from 4.20% in 2023 to 4.30% in 2024 and 4.50% in 2025, based on our assumptions about the future path of Fed policy and market interest rates. This would imply that private sector interest expense as a share of current private sector gross output will rise from 3.35% in 2023 to 3.40% in 2024 and 3.60% in 2025, an increase of 0.25pp from 2023 to 2025.

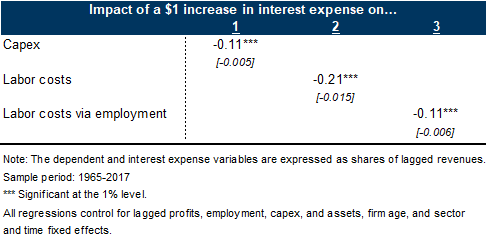

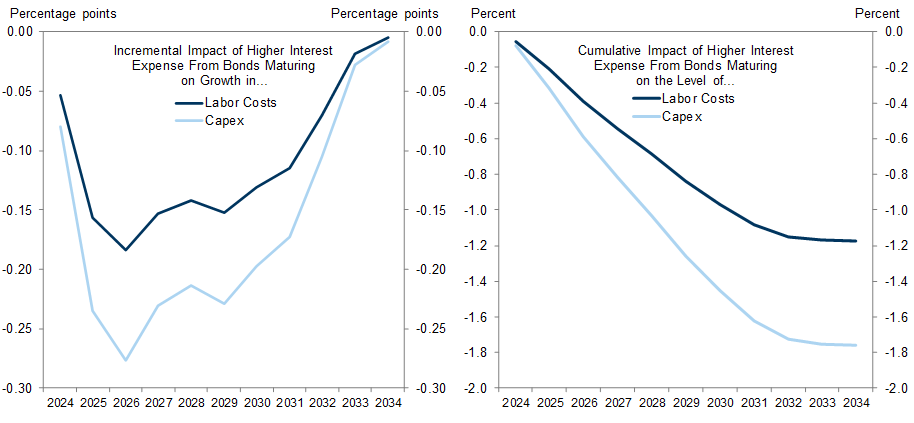

We find that for each additional dollar of interest expense, firms lower their capital expenditures by 10 cents and labor costs by 20 cents. The increase in interest expense that we estimate would therefore reduce capex growth by 0.10pp in 2024 and 0.25pp in 2025 and labor cost growth by 0.05pp in 2024 and 0.15pp in 2025. Our estimates suggest about half of the reduction in labor costs comes from reduced hiring and half from lower wage growth, implying a 5k drag on monthly payrolls growth in 2024 and a 10k drag in 2025.

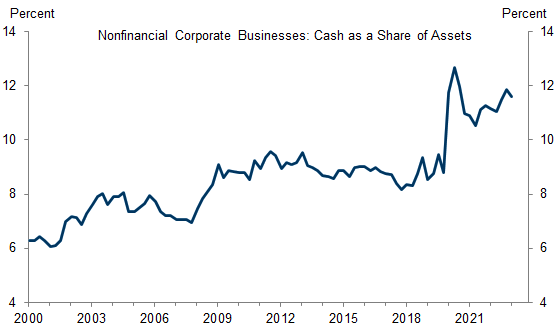

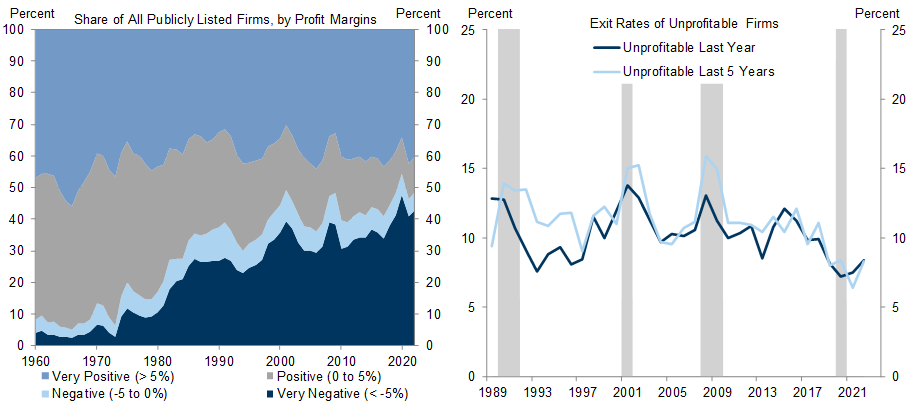

We see reasons why the hit from higher interest expense could be either smaller or larger than usual. On one hand, cash balances are historically high, which could help buffer the hit. On the other hand, the number of unprofitable firms has continued to proliferate, as the exit rate of unprofitable firms has declined since the start of the pandemic. In previous research, we have found that unprofitable firms disproportionately cut back on capex and employment when faced with margin pressure.

The Corporate Debt Maturity Wall: Implications for Capex and Employment

The Spillovers From Higher Interest Expense to Capex and Employment

Ronnie Walker

Sienna Mori

- 1 ^ Our equity strategists have flagged that larger firms tend to have less cash on hand, with cash as a share of assets having roughly returned to pre-pandemic levels for the S&P 500, suggesting that smaller firms have particularly large buffers.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.