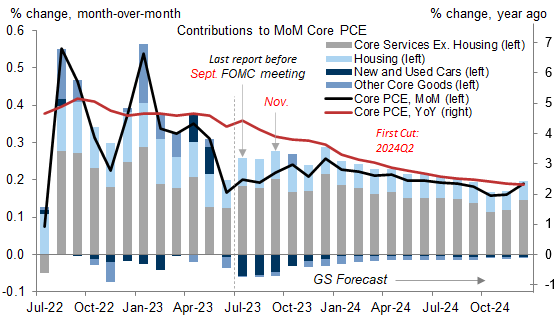

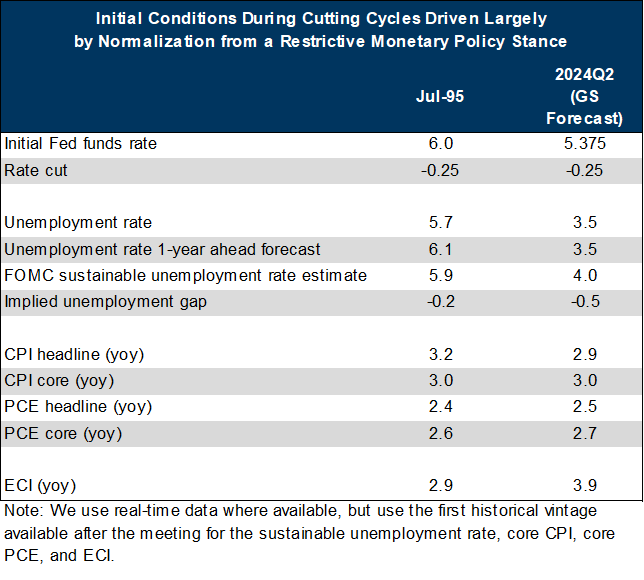

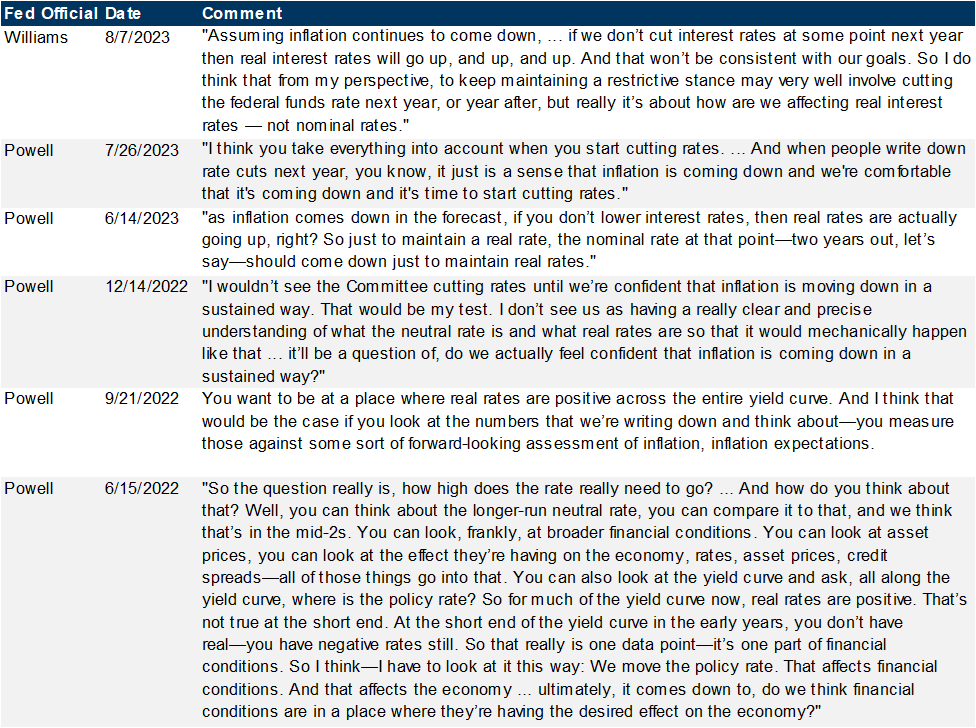

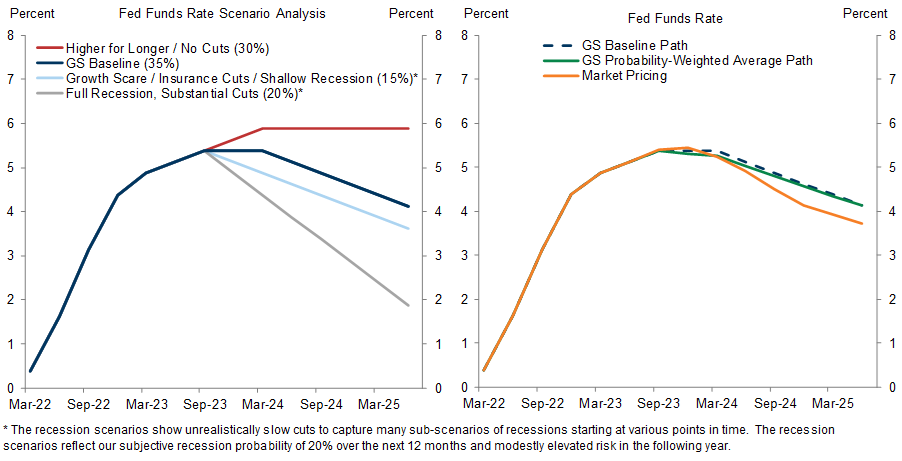

Our baseline forecast calls for the FOMC to start cutting the funds rate in 2024Q2. At that point, we expect core PCE inflation to have fallen below 3% year-on-year and below 2.5% on a monthly annualized basis. The motivation for cutting outside of a recession would be to normalize the funds rate from a restrictive level back toward neutral once inflation is closer to the target.

Normalization is not a particularly urgent motivation for cutting, and for that reason we also see a significant risk that the FOMC will instead hold steady. The FOMC might not cut because inflation might not fall enough or, even if it does, because solid growth, a tight labor market, and a further easing of financial conditions might make cutting seem like an unnecessary risk.

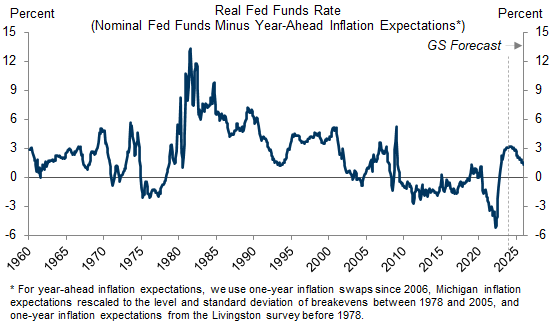

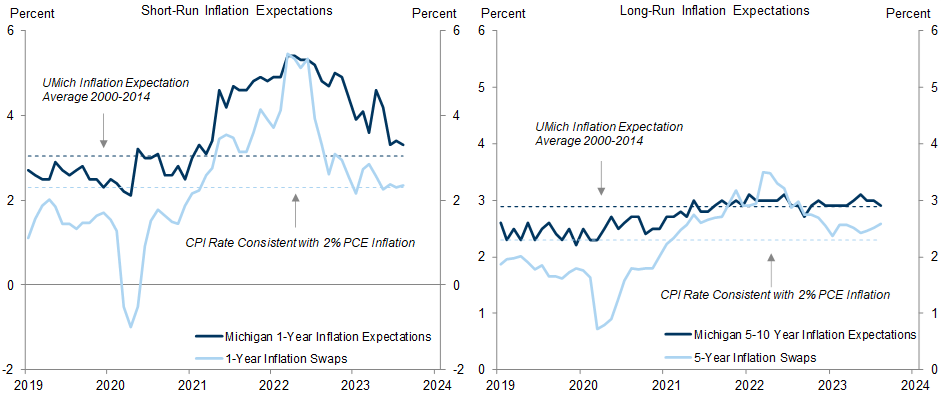

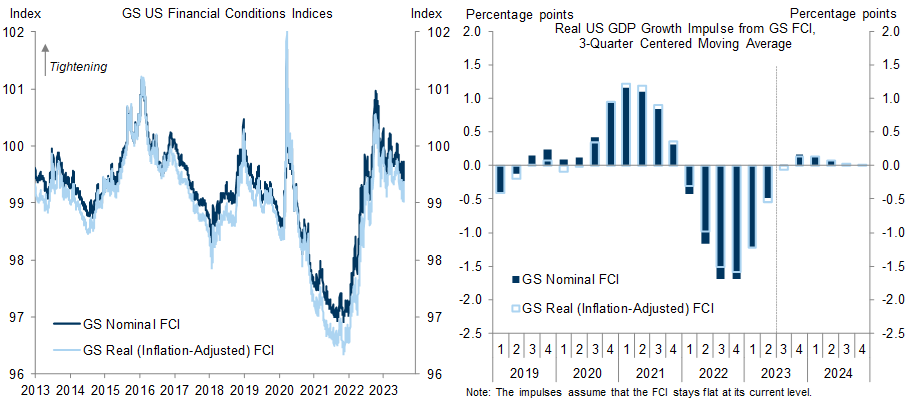

Some Fed officials and investors argue that the FOMC must cut as inflation falls to prevent real interest rates from rising and hurting the economy. We disagree with this logic. Real interest rates should be calculated by subtracting off forward-looking inflation expectations, not realized inflation, and inflation expectations have already fallen to or nearly to target-consistent levels. Moreover, adjusting our broader financial conditions index (FCI) for inflation rather than the funds rate has very little impact on the implied impulse to GDP growth, which is now modest.

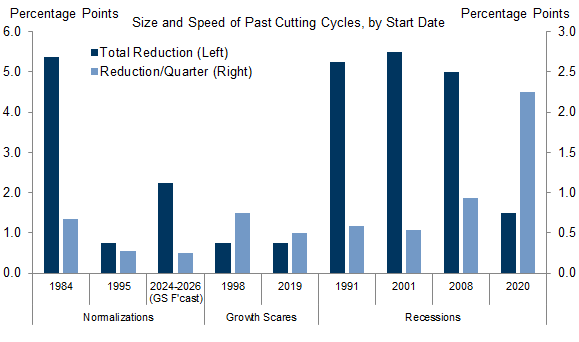

We are penciling in 25bp of cuts per quarter but are uncertain about the pace. The FOMC might move slowly if its desire to normalize is only lukewarm and it fears further boosting asset prices and strengthening an economy with an already-tight labor market, or it could cut more quickly from a high starting point if it is more confident that the inflation problem is unlikely to return.

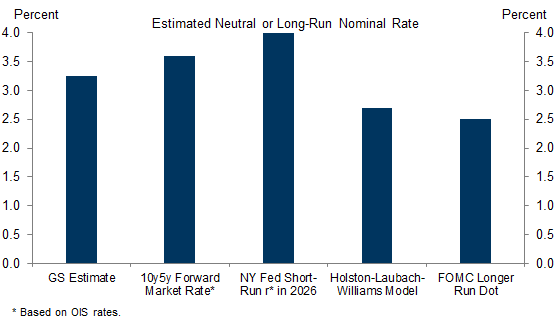

We expect the funds rate to eventually stabilize at 3-3.25%, above the FOMC’s 2.5% median longer run dot. We have long been skeptical that neutral was as low as widely thought last cycle, and larger fiscal deficits have arguably pushed it higher since. Fed officials could raise their longer run dots if the economy remains resilient with the funds rate at a much higher level or they could conclude—as a recent New York Fed blog post did—that the short-run neutral rate is elevated.

Our views have been more hawkish than market pricing this year because we have seen both a lower probability of recession than consensus and a relatively high threshold for rate cuts. This remains true, though the gap has narrowed as recessions fears have faded. We think it is appropriate for the yield curve to be inverted, but not quite as much as it is.

Rate Cuts

Exhibit 2: Our Baseline Forecast Calls for Rate Cuts Without a Recession Because Once Inflation Comes Down, the Funds Rate Will Not Need to Remain High Relative to Recent History and Estimates of Neutral

David Mericle

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.