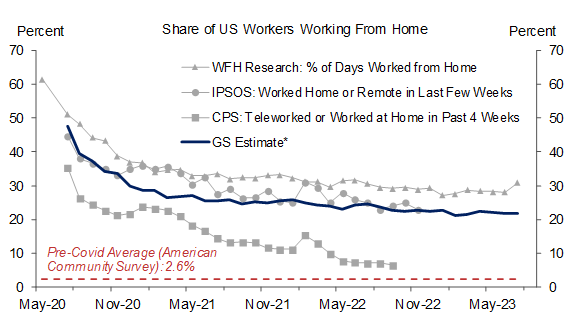

The share of US workers working from home (WFH) at least part of the week has stabilized at around 20-25%, below its peak of 47% at the height of the pandemic but well above the pre-pandemic average of 2.6%. In this US Daily, we discuss the implications of WFH for office demand, consumer spending, and productivity.

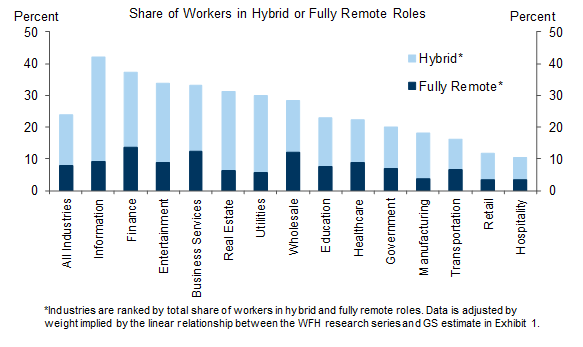

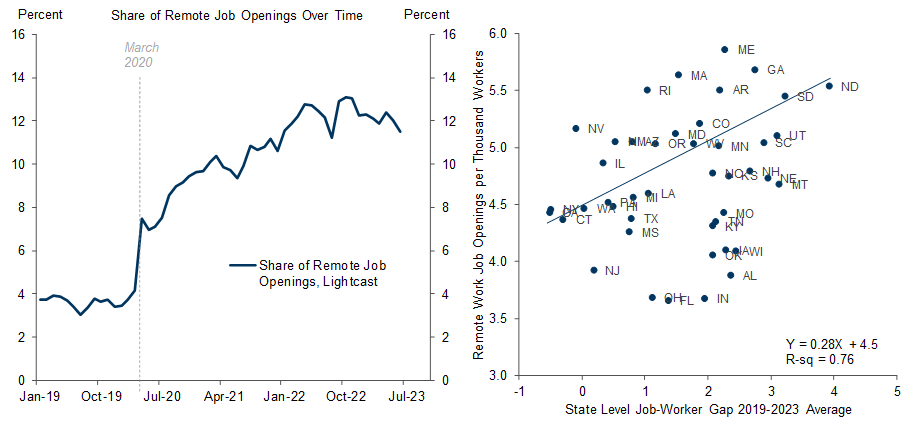

The persistence of WFH reflects both structural and cyclical factors. Structurally, the pandemic-related lockdowns spurred technological innovations that make teleworking easier, and surveys show that workers now place more value on being able to work from home. Cyclically, tight labor markets over the last two years have made employers more willing to allow employees to work remotely. Using state-level data, we find that a 1pp increase in the job-worker gap leads to a 0.3pp increase in the share of remote job postings. This implies that further labor market rebalancing should reduce the share of remote job postings from 11.5% to 10.8% in the next 3 years.

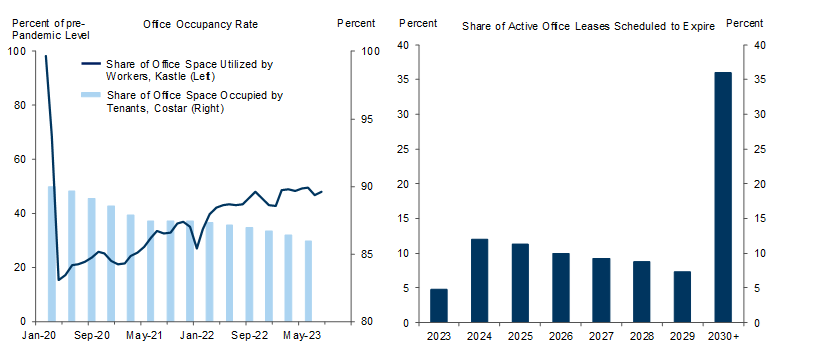

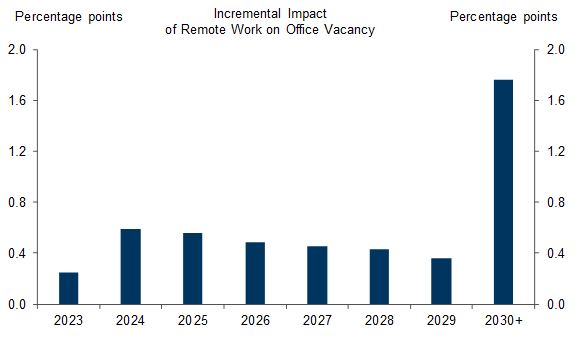

WFH has reduced office utilization rates but has not yet led to substantial declines in office occupancy rates because most firms are locked in long duration leases. Going forward, 17% of all office leases are scheduled to expire by the end of 2024, 47% between 2024-2029, and the rest after 2030. Our baseline estimates suggest that remote work will likely exert 0.8pp of upward pressure on the office vacancy rate by 2024, an additional 2.3pp over 2025-2029, and another 1.8pp in 2030 and beyond, though this is likely to be partially offset by a decline in new construction.

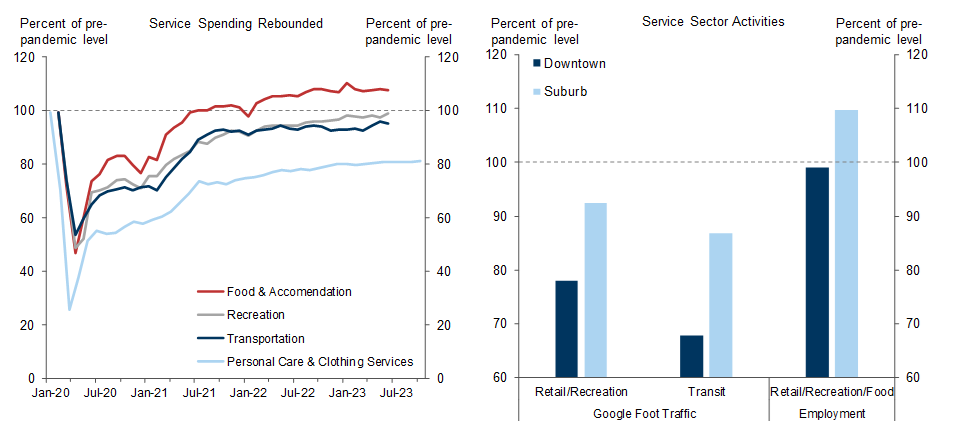

The shift to remote work has also changed the geographic distribution of retail spending and employment. While spending on services that require face-to-face contact has now fully recovered in the aggregate, the recovery has been skewed towards suburban areas and away from city centers where traditional office-related activities take place.

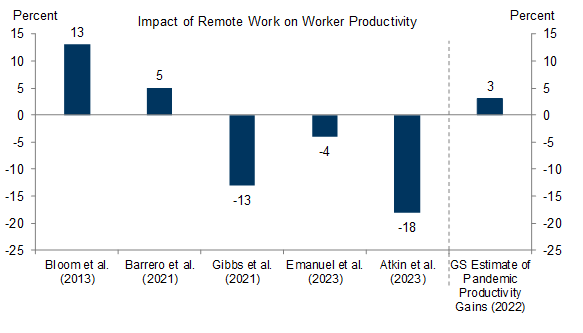

Economic studies disagree on the productivity effects of WFH, with estimates ranging from -19% to +13% and compared to our baseline of +3% for pandemic productivity gains more generally. The lack of consensus across these studies is likely driven by differences in how they measure productivity and the types of tasks and industries they study. More recent studies that measure productivity through complex performance metrics in industries involving high-cognitive tasks reveal more negative effects.

Remote Work, Three Years Later

Exhibit 1: The Share of Workers Working at Least Partly Remotely Has Declined by Roughly Half From Its Peak to Around 20-25%

Exhibit 5: Office Vacancy Rates Will Rise if WFH Rates Stay Elevated

Exhibit 6: Real Spending on Services Has Rebounded, but Recovery Is Skewed Away From Downtown Office Areas

- 1 ^ Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom, 2021 “The Donut Effect of Covid-19 on Cities”

- 2 ^ See Pew Research Center Survey, WFH Research, Flex Survey

- 3 ^ We estimate a 1% increase in office vacancy rate is associated with a $10.8 billion decline in fixed investment for office structures.

- 4 ^ Michael Gibbs, Friederike Mengel, and Christoph Siemroth, 2021 “Work from home and productivity: evidence from personnel and analytics data on IT professionals”David Atkin, M. Keith Chen, and Anton Popv, 2022 “The returns to face-to-face interactions: knowledge spillovers in Silicon Valley”Emanuel and Harrington 2023 “Working remotely? Selection, treatment, and the market for remote work”David Atkin, Antoinette Schoar, and Sumit Shinde 2023 “Working from home, worker sorting and development”

- 5 ^ Nicholas Bloom, James Liang, John Roberts, and Zhichun Jenny Ying, 2013 “Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment”

- 6 ^ Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis, 2021 “Why working from home will stick”

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.