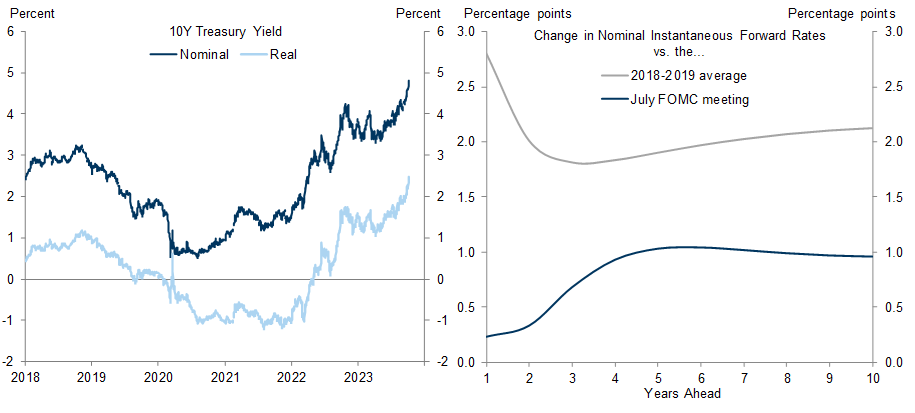

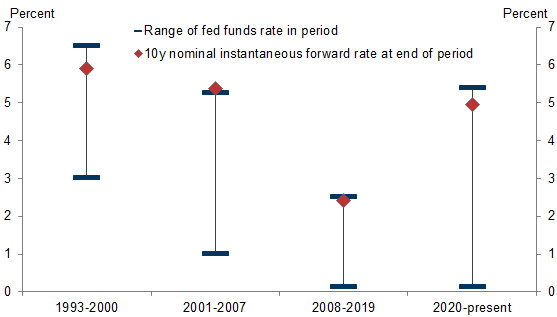

Interest rates have risen across the curve in recent months even as the hiking cycle has increasingly looked finished. Rates have risen moderately at the front end as it has become less clear whether falling inflation will be enough to prompt cuts anytime soon. And rates have risen sharply further out the curve as investors have inferred from the economy’s strong performance at a 5%+ fed funds rate that the neutral or equilibrium interest rate might be much higher than was widely assumed last cycle, when markets embraced the secular stagnation hypothesis.

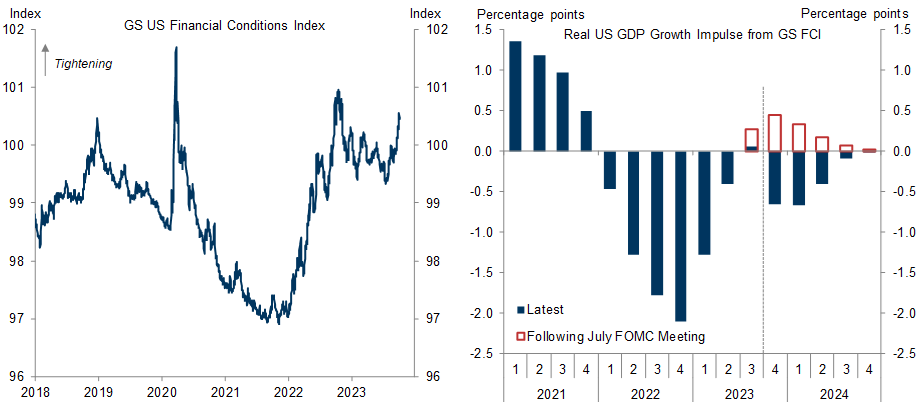

The main implication of the further tightening in financial conditions led by rising rates is that the drag on GDP growth will last longer. We now estimate a roughly -½pp hit to growth over the next year, meaningful but much less than last year and too small to threaten recession.

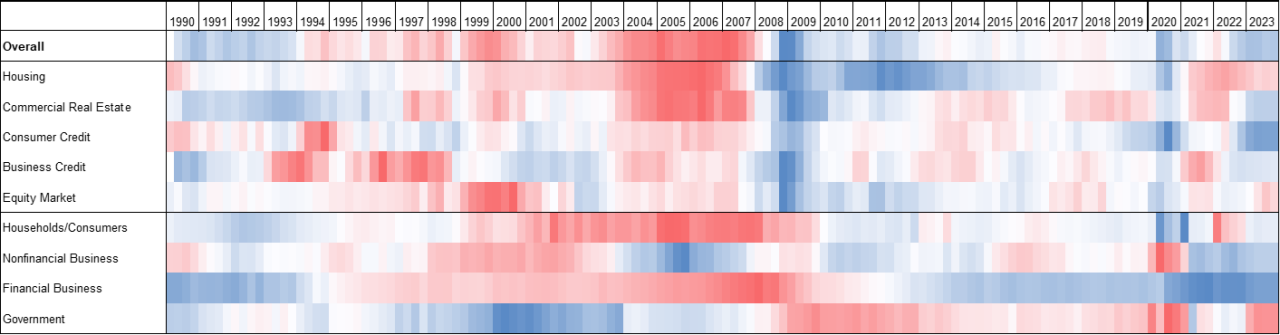

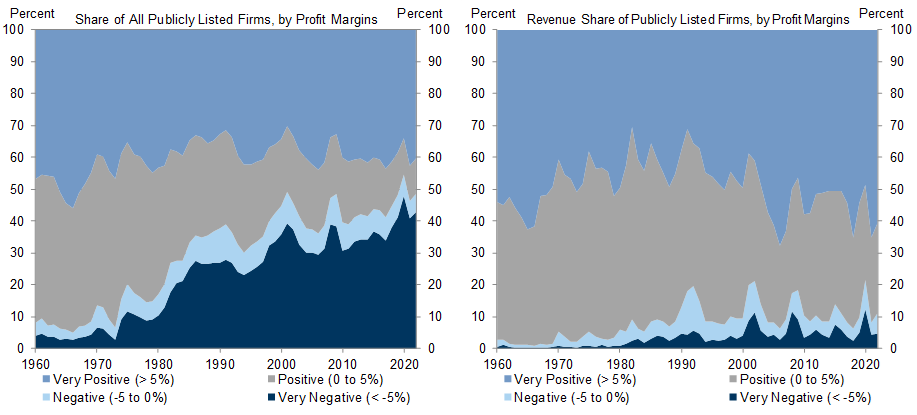

The move to a higher rate regime poses other risks too. Last cycle, the belief that real rates would remain close to zero in the future helped to rationalize a few major economic trends that would otherwise have looked more questionable: elevated valuations of risky assets in financial markets, the surprising survival of persistently unprofitable firms in the corporate sector, and wide deficits that added to an already historically large federal debt in the public sector. We explore what the economic consequences might be if these trends were to begin to unwind.

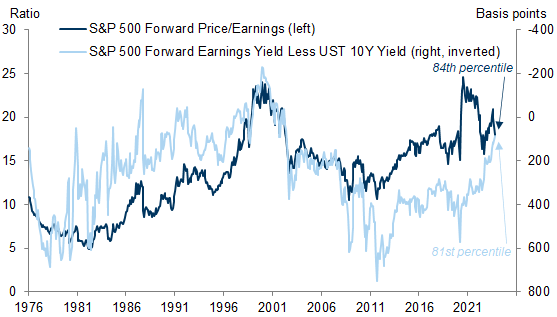

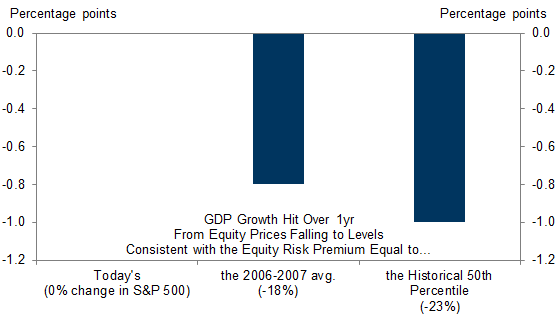

In financial markets, the key risk is that valuation measures that are benchmarked to interest rates are now higher for some assets, most importantly stocks. We estimate that if the equity risk premium fell to its 50th historical percentile, the hit to GDP growth over the following year would be 1pp. If it fell to its average level in the pre-GFC years, the hit would be 0.75pp.

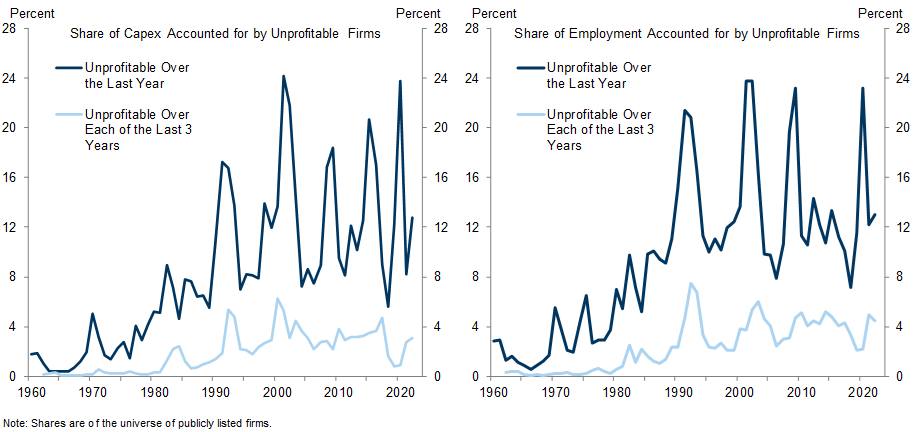

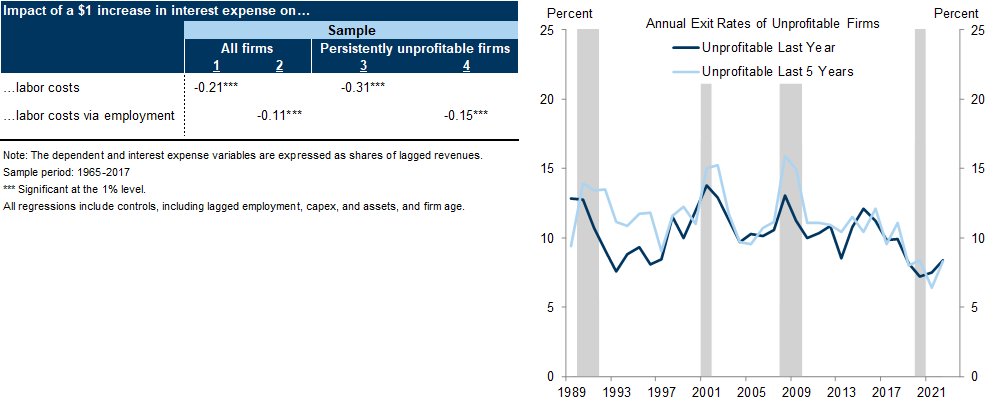

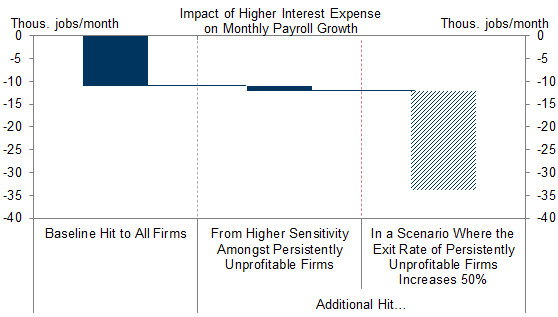

In the corporate sector, investors might hesitate to continue financing unprofitable companies that they hope will pay off well down the road now that the opportunity cost has risen. That could force these companies to close or cut labor costs more aggressively, as they have tended to do when hit with interest rate shocks in the past. A 50% increase in their exit rate would impose a roughly 20k drag on monthly payroll growth and a roughly 0.2pp hit to GDP growth.

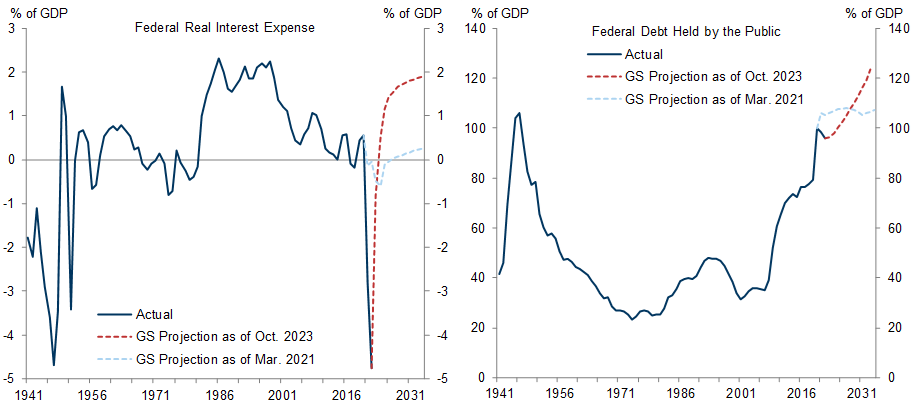

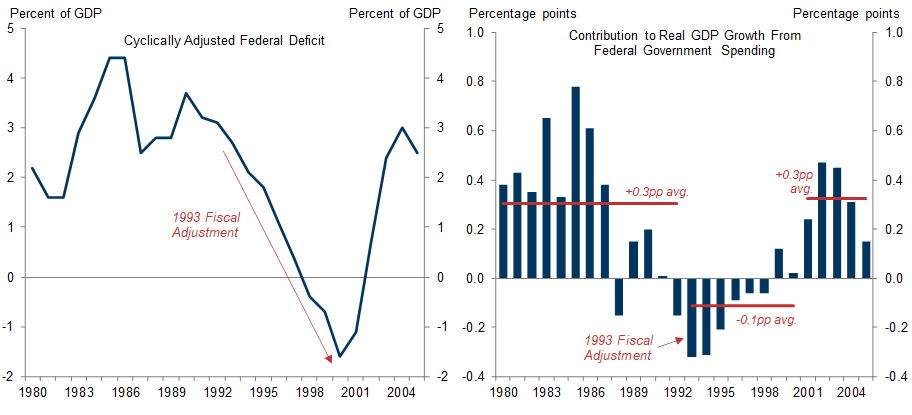

In the public sector, projections of real interest expense and the federal debt-to-GDP ratio look much worse than just a couple of years ago, when the interest rate on government debt (r) was expected to remain well below nominal GDP growth (g). We think it is unlikely that concern about debt sustainability will lead to a deficit reduction agreement anytime soon. But if it does happen eventually, an agreement similar in magnitude to the 1993 fiscal adjustment would imply a hit to GDP growth in the neighborhood of as much as ½pp per year for a number of years.

While these risks are significant, they are probably not large enough individually to trigger a recession unless they occur abruptly and aggressively or simultaneously. And in those scenarios, we think that the Fed would likely deliver rate cuts that would offset much of the impact.

The Risks of a Higher Rate Regime

The Risks of a Higher Rate Regime

The Risk from Financial Asset Valuations

The Risk from Unprofitable Firms

The Risk of a Fiscal Adjustment

Higher Rates Are a Moderate Headwind to Growth, Not a Recessionary Shock

David Mericle

Ronnie Walker

- 1 ^ Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul and Fabian Winkler, “The Natural Rate of Interest Through a Hall of Mirrors,” 2022.

- 2 ^ Samuel G. Hanson and Jeremy C. Stein, “Monetary policy and long-term real rates,” Journal of Financial Economics, 2015.

- 3 ^ Researchers at the OECD and BIS have noted that the increase in unprofitable firms has occurred across advanced economies and have linked the rise in part to lower interest rates. See Müge Adalet McGowan, Dan Andrews, and Valentine Millot, “The Walking Dead? Zombie Firms and Productivity Performance in OECD Countries,” 2017; Ryan Niladri Banerjee and Boris Hofmann, “The Rise of Zombie Firms: Causes and Consequences,” 2018.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.