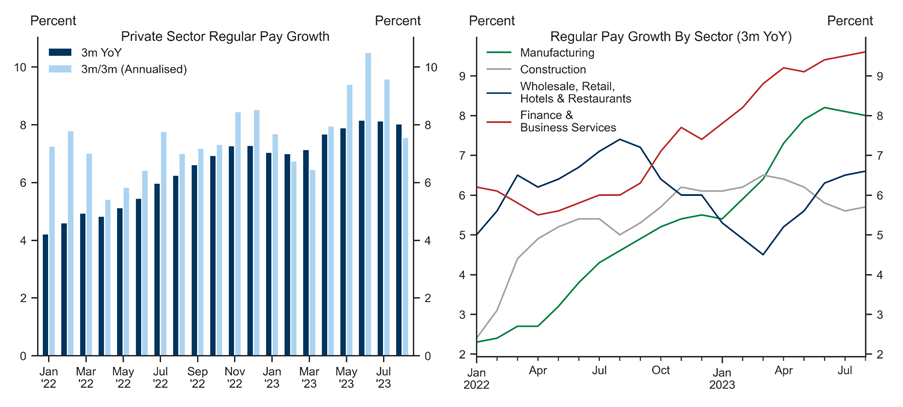

Elevated wage growth has been an important factor in pushing Bank Rate higher. The BoE has noted that wage growth has exceeded the predictions of standard models, and Deputy Governor Broadbent has suggested that higher structural unemployment could explain this disparity. In this Analyst, we assess whether the structural unemployment rate has risen, how to explain elevated wage growth, and the outlook for pay pressures.

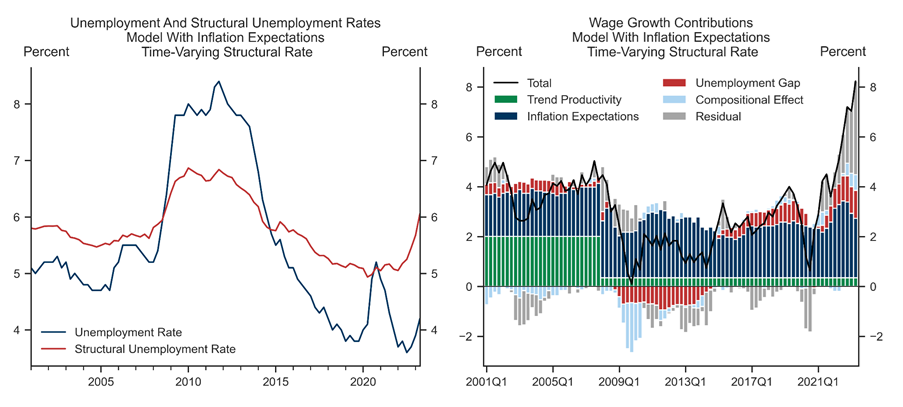

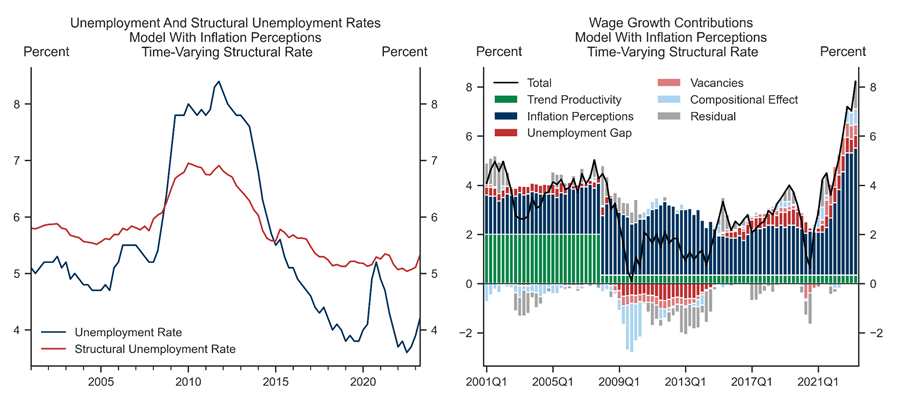

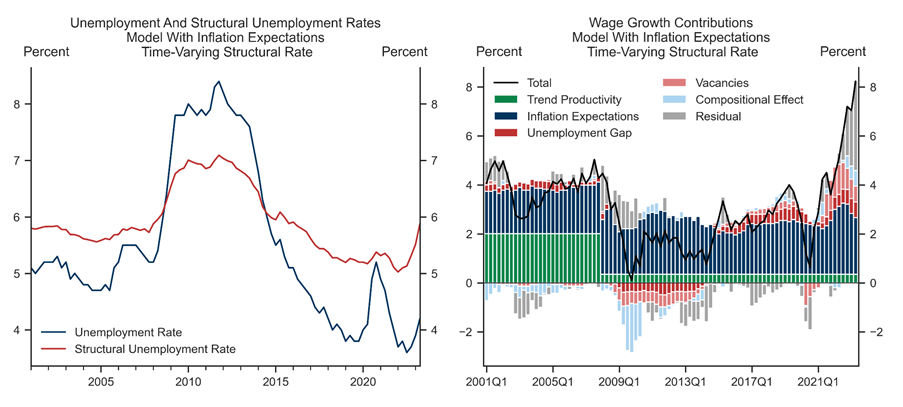

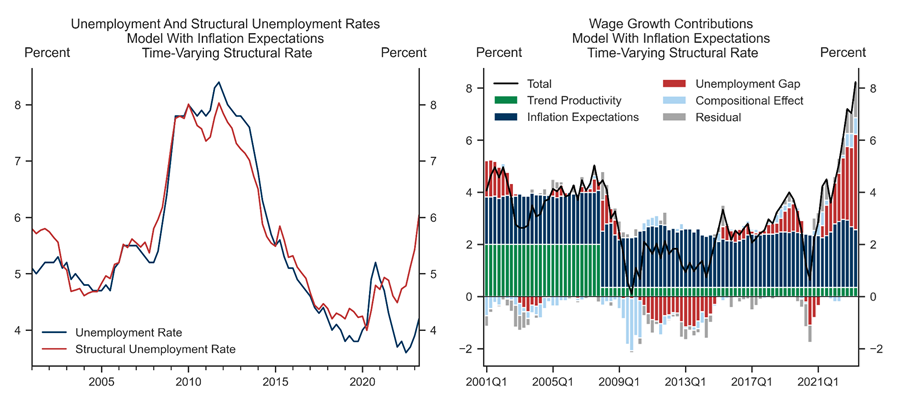

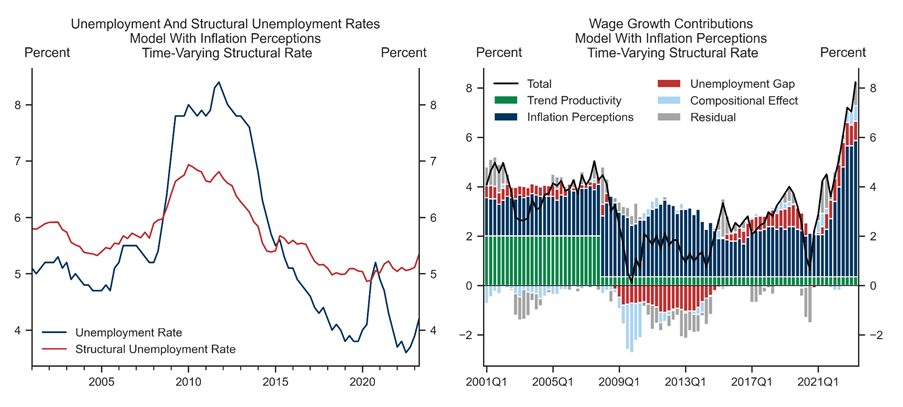

We begin by using statistical models to estimate the structural unemployment rate. Models based on unemployment and inflation expectations struggle to explain high wage inflation and so point to a steep rise in structural unemployment since the pandemic. However, models driven by consumers’ perceptions of past inflation rather than their expectations fit the recent data better and suggest that structural unemployment has risen very little since 2019.

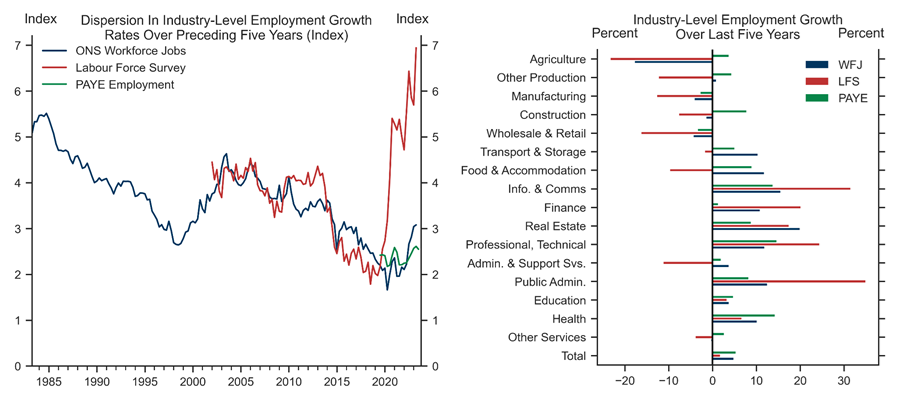

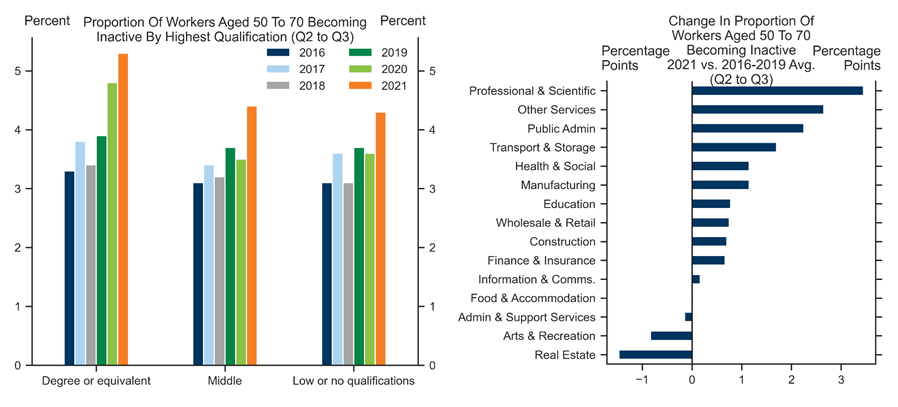

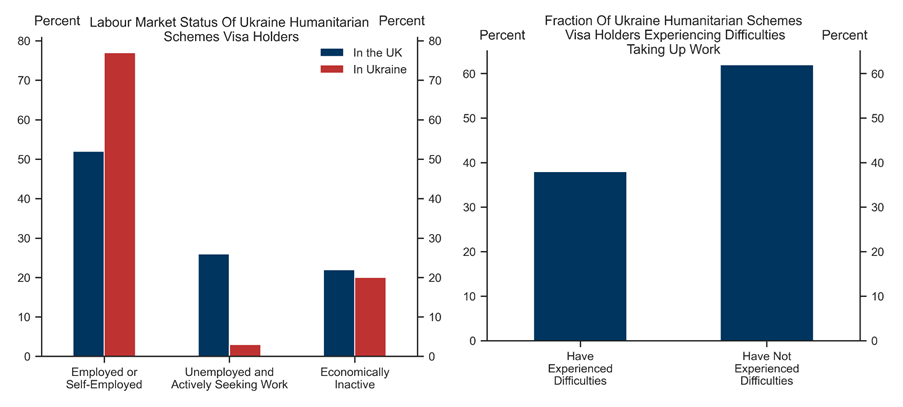

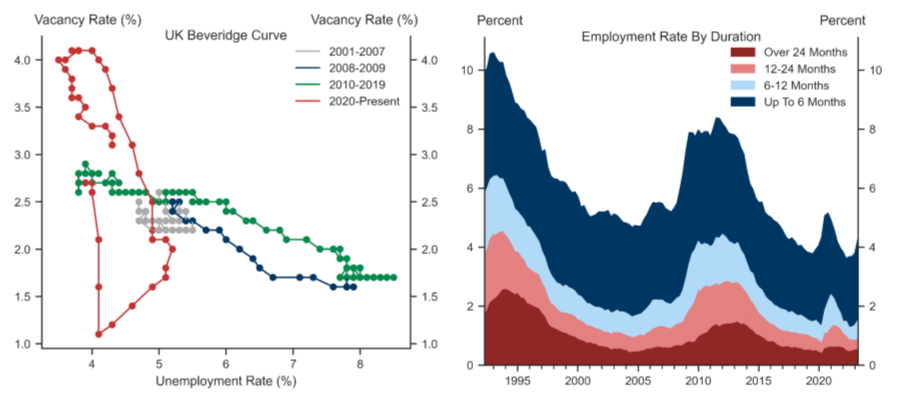

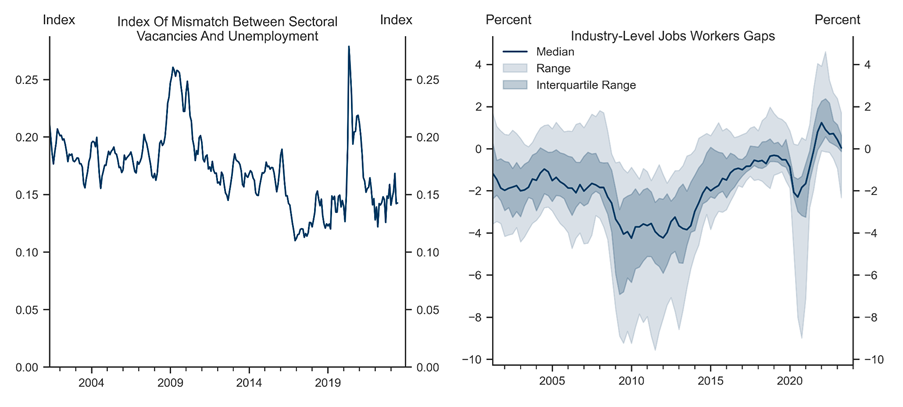

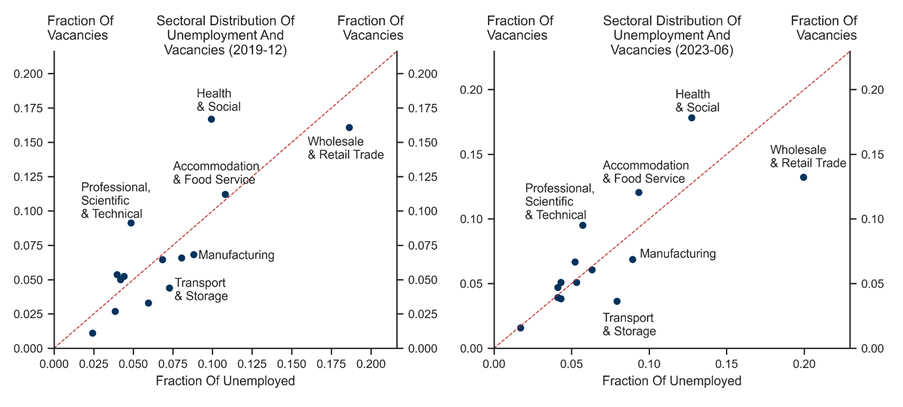

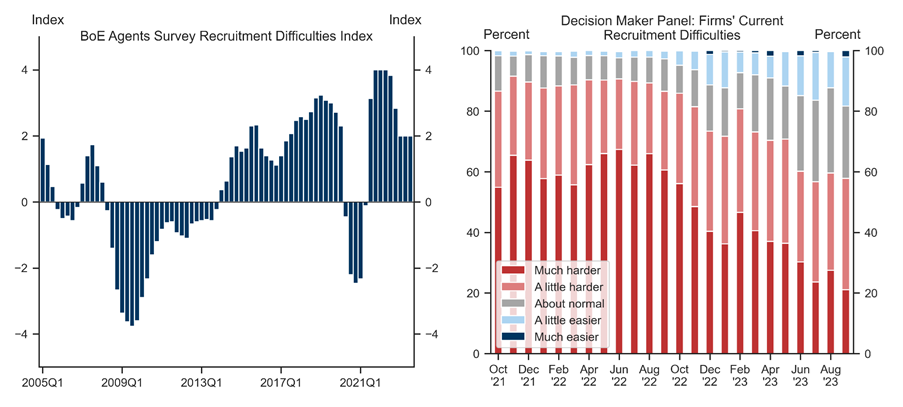

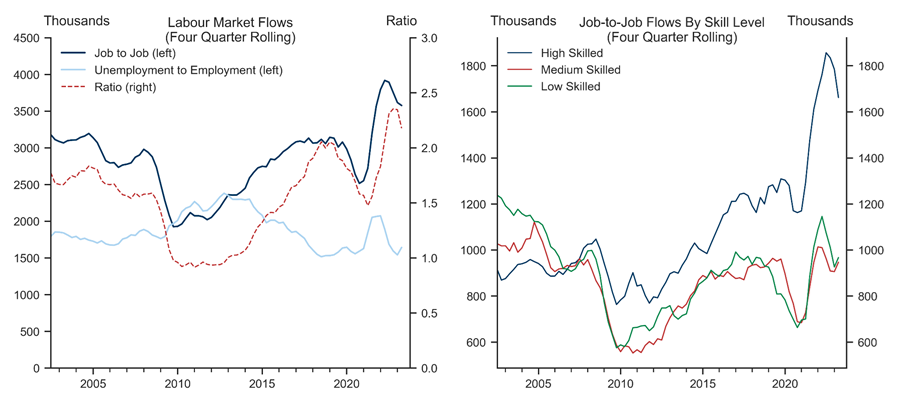

We then assess the bottom-up drivers of labour market mismatch. Several factors point to rising mismatch and hence structural unemployment during the pandemic, notably changing migration patterns and certain industries being disproportionately affected by early retirements. That said, quantitative measures of mismatch have fallen back from post-pandemic peaks and now stand close to 2019 levels.

In our view, the balance of evidence suggests that structural unemployment is likely only modestly higher than pre-pandemic levels. However, our models imply that the labour market was already tight before the pandemic. As such, even if the structural rate has not risen by much, we still find that it lies well above the current unemployment rate, indicating that the labour market remains tight in levels terms. Indeed, our models imply a structural rate that is notably higher than the BoE’s estimates.

Our models suggest that elevated labour market tightness has contributed to high wage growth, although the pass through of price inflation has been a more important driver. That said, our previous research suggests that the pass through from price inflation to wages may have been faster because the labour market is tight, an interaction effect that our models would not capture, potentially pointing to a more important role for slack.

We expect wage pressures to ease in the near-term given falling headline inflation and continued monetary policy drag pushing unemployment slightly higher. We expect that will allow the BoE to hold rates at 5.25%. However, we do see a possibility that wage growth normalisation could slow in 2024 as the labour market remains tighter than historical averages, pointing to risks that the BoE could need to hike further at that juncture.

UK—Can Higher Structural Unemployment Explain Pay Pressures?

A Statistical Approach

The Drivers of Mismatch

Quantitative Measures of Mismatch

Has Structural Unemployment Risen?

Explaining Pay Pressures

The Outlook for Wage Growth

Appendix

Model Description

Model With Vacancies And Inflation Expectations

Model With Looser Prior on Variability Of Structural Rate

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.