Given the focus on how the market may adjust to any conflict-related decline in Middle Eastern output and on the largest US upstream acquisition in 25 years, we answer questions on the world’s marginal producer, namely the US.

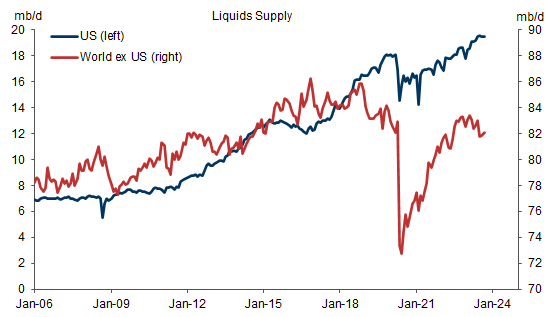

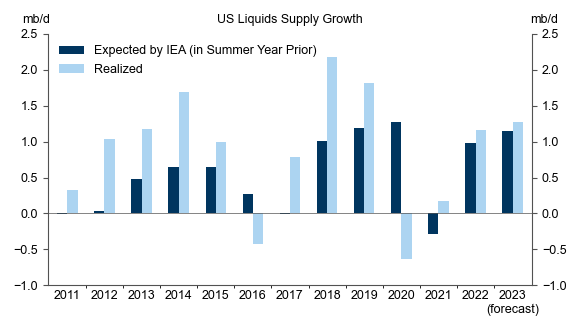

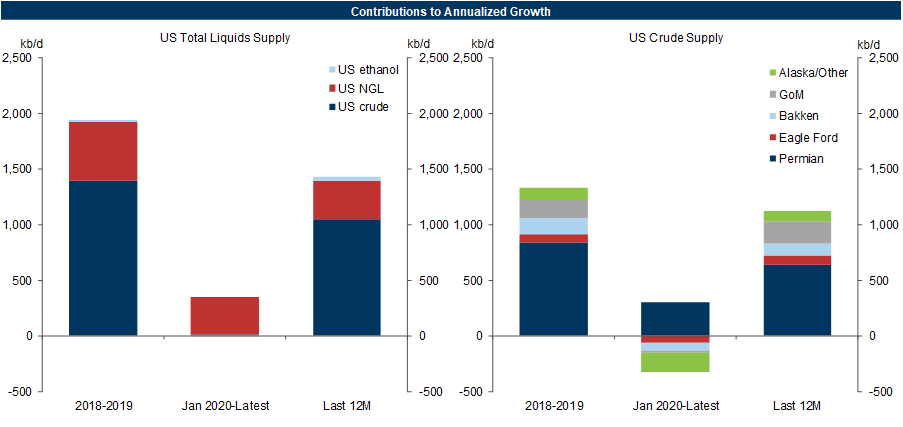

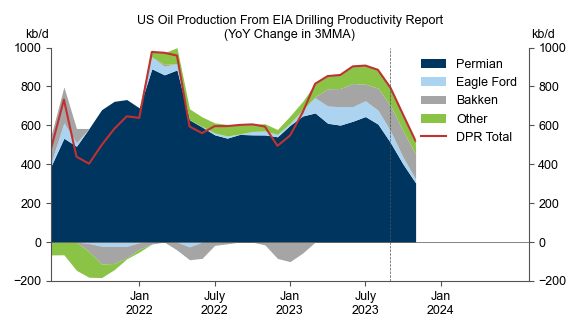

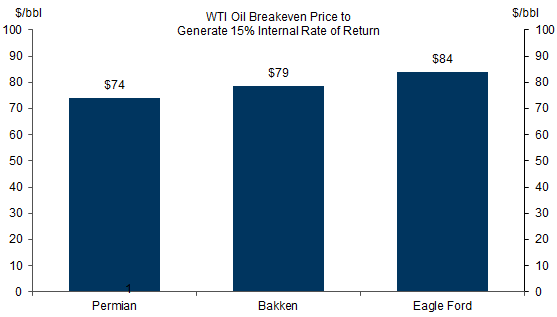

The US has driven all the growth in global oil supply over the past decade and the past year, and the Permian basin has driven all growth in US crude supply since early 2020. The US remains the key short-term marginal oil producer, where flexible short-cycle private producers sit high on the global cost curve.

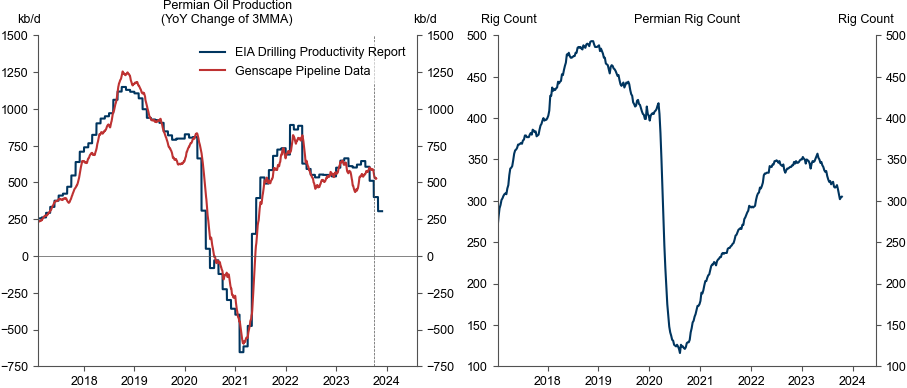

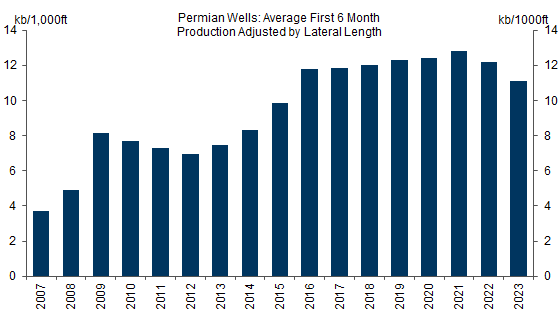

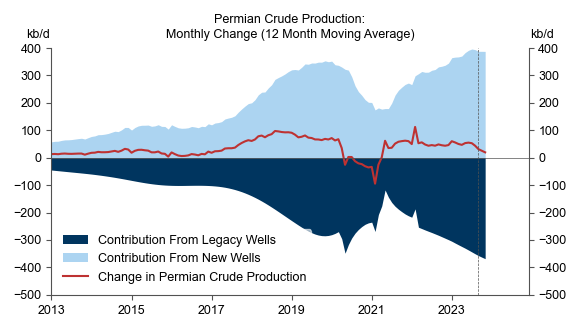

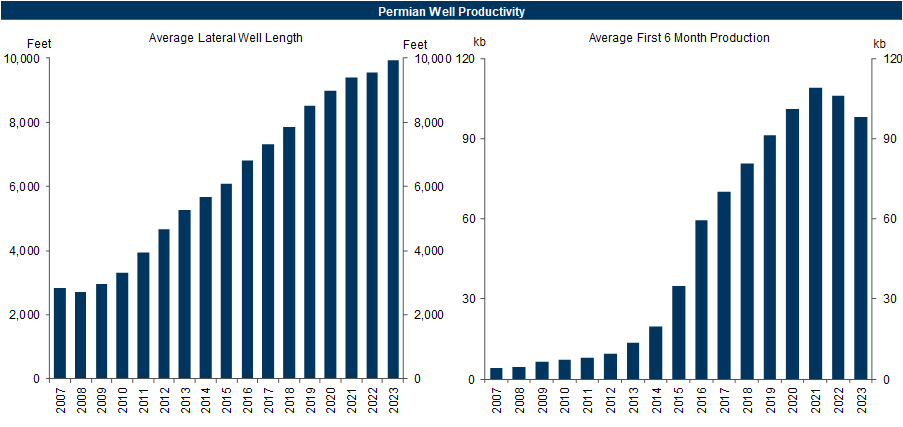

Crude output growth in the Permian has slowed from 1mb/d in 2019 to 0.5mb/d year-over-year in September given the drop in the rig count, and the stabilizing well productivity trend. Permian output, however, is still edging up because of rises in the number of drilled wells per rig and well length. The lack of well productivity growth (which reflects an offset between deteriorating rock quality and improving technology) suggest that Permian output growth will slow further.

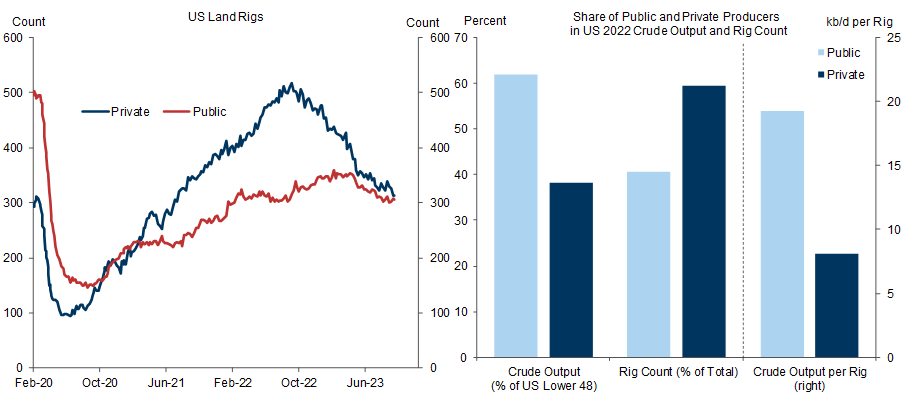

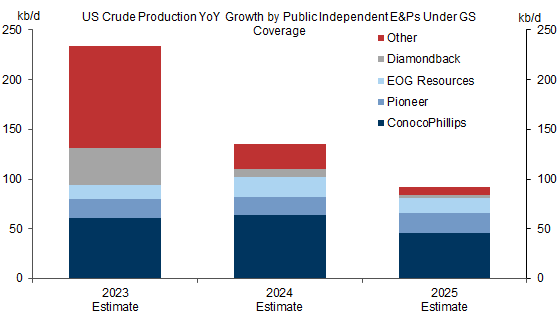

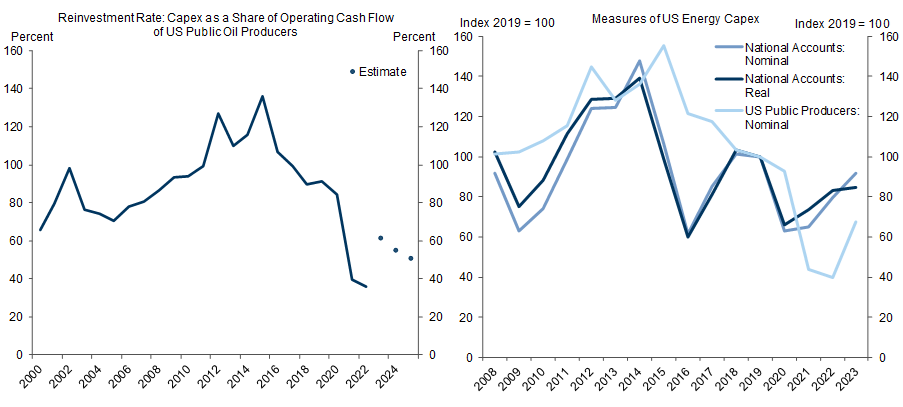

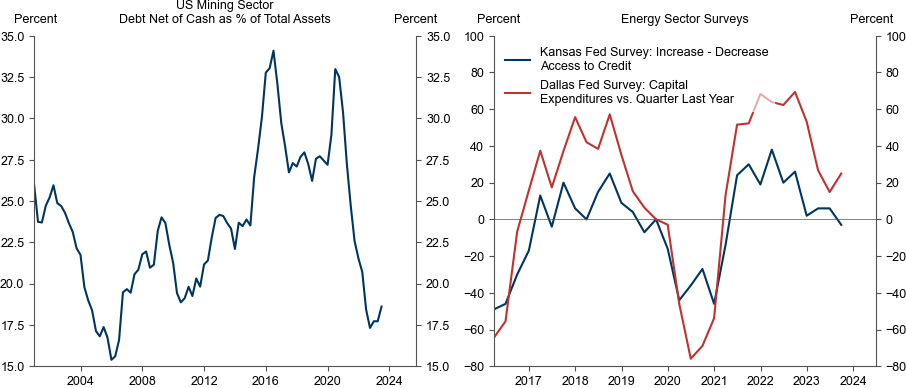

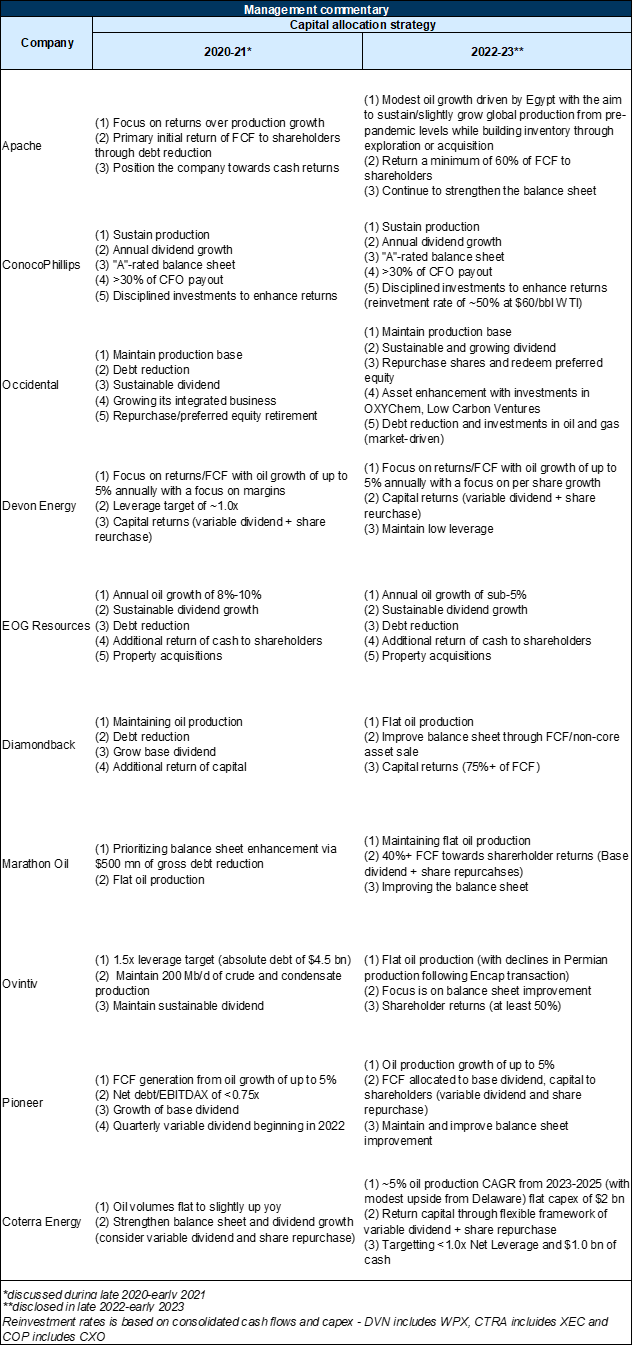

US oil producers remain capital disciplined. US public firms are sticking to their moderate and price insensitive growth targets, and capex has moved up only moderately from low levels. Consolidation and high interest rates only have a muted effect on aggregate production as investment is largely self-financed, and only small private firms report significant credit effects.

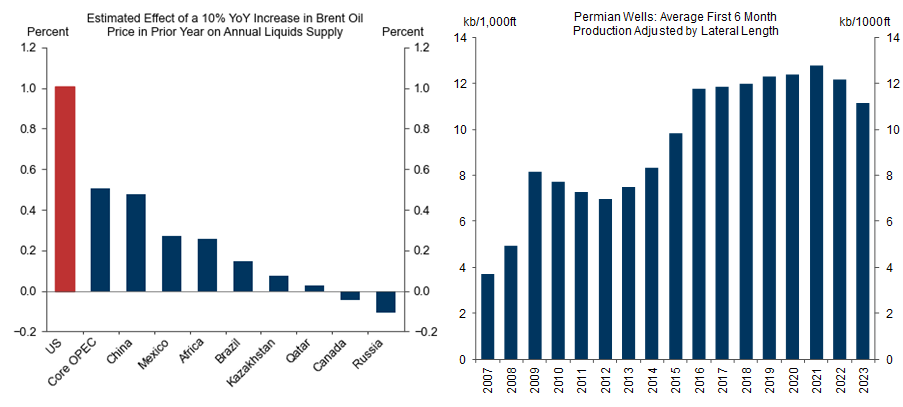

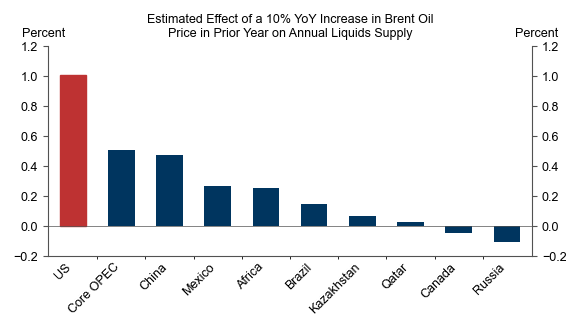

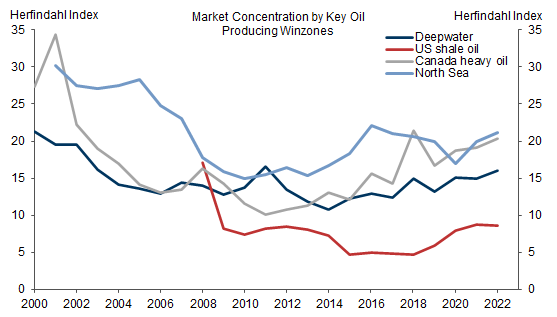

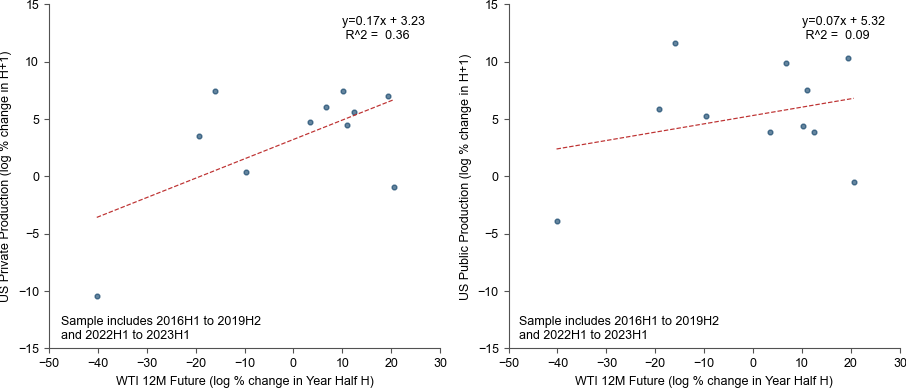

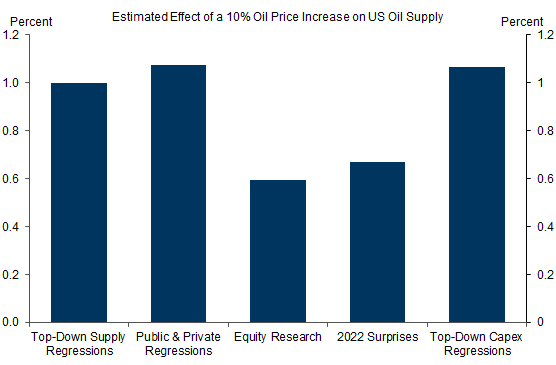

We find that the elasticity of US supply has fallen over time, and is much smaller for public producers than for privates. We estimate that a 10% oil price increase boosts US liquids supply by around 1% or 200kb/d. Consolidation is likely to further depress the supply elasticity as inelastic public producers gain market share, and efficiency gains push the US lower on the cost curve.

We see two takeways. First, the trends in the Permian and ongoing capital discipline support our forecasts that US liquids supply growth slows in 2024 to 0.6mb/d (vs.1.4mb/d in 2023), and that Brent reaches $100/bbl in June. Second, our estimates imply that the US supply response to higher prices—caused by any geopolitical supply shock—would offset only about 20-25% of the initial shock, which underscores OPEC’s key role in balancing the market. While core OPEC countries currently have nearly 4mb/d of spare capacity, physical or political barriers to deploying spare capacity are the key upside risk to oil prices.

US Shale: The Marginal Supplier Matures

US supply trends and whether the US remains the key marginal producer

Fundamentals in the Permian play (the key growth engine)

The impact of capital discipline, consolidation, and high rates on US supply

The elasticity of US supply and geopolitical shocks

US Supply Trends

Exhibit 5: Oil Supply Is More Price Elastic in the US

Permian Slowing Fundamentals

Exhibit 8: An Increasingly Negative Contribution to Permian Crude Growth From Legacy Wells

A rise in the number of drilled wells per rig given progress in multi-well pad technology

A structural rise in the average lateral well length to 10,000 feet[4] (Exhibit 9)

A boost to output per rig through a composition effect arising from the larger drop in less productive private rigs (“high grading”). The output per rig in 2022 was nearly 2.5 times greater for public rigs than for private rigs since public firms account for over 60% of production, but under 40% of rigs (Exhibit 10).

Capital Discipline, Consolidation, and Higher Rates

The US Supply Response to Oil Prices

Appendix

- 1 ^ The IEA defines total liquids as the sum of crude oil (including condensates), natural gas liquids, and nonconventional oils.

- 2 ^ Short-cycle fields are not limited to the US. There are also tight oil projects—which can be extracted from shale formations, sandstone and carbonates—in Canada, Argentina, and China.

- 3 ^ Canada’s Montney shale field has a low oil-to-gas ratio, and Argentina’s Vaca Muerta shale oil is pumped by larger producers with stickier output plans.

- 4 ^ ExxonMobil discussed drilling "industry-leading longer laterals (up to 4 miles)", which corresponds to 21,120 feet, in the October 11th presentation updating investors on the deal with Pioneer.

- 5 ^ Exxon believes it can drive $2 bn of synergies beginning in the second year post-closing, the bulk of which is through capital efficiency benefits (improved resource recovery driving 2/3 of the improvement and 1/3 from capex and opex synergies) as well as incremental G&A savings.

- 6 ^ The elasticity of large private producers is between the low elasticity of public producers and the high elasticity of small private producers. As public producers, large private producer want to preserve inventory to protect exit options.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.