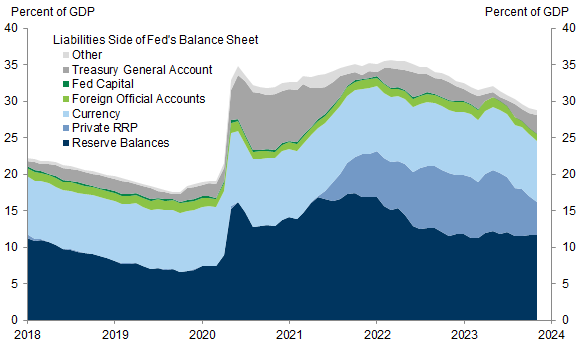

Since last year, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk by roughly $1.2tn to $7.8tn, and balance sheet runoff has proceeded smoothly so far. In today’s note, we provide an update of our Fed balance sheet projections and lay out a series of indicators we are watching to track conditions in money markets.

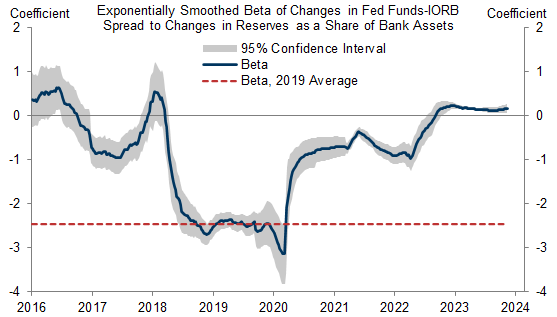

The FOMC will likely aim to stop balance sheet normalization when bank reserves go from “abundant” to “ample”—that is, when changes in the supply of reserves have a real but modest effect on short-term rates. We expect the FOMC to begin considering changes to the speed of runoff around 2024Q3, to slow the pace in 2024Q4, and to finish runoff in 2025Q1. At that point, we expect bank reserves to be around 12-13% of bank assets and the Fed’s balance sheet to be around 22% of GDP (vs. around 30% currently and 18% in 2019). The key risk to our forecast is that the increased supply of debt that we expect in 2024 causes intermediation bottlenecks in the Treasury market that lead the Fed to stop runoff earlier.

We continue to expect the Fed’s remaining balance sheet runoff to have modest effects on interest rates, broader financial conditions, growth, and inflation—much less than the impact of interest rate hikes this cycle.

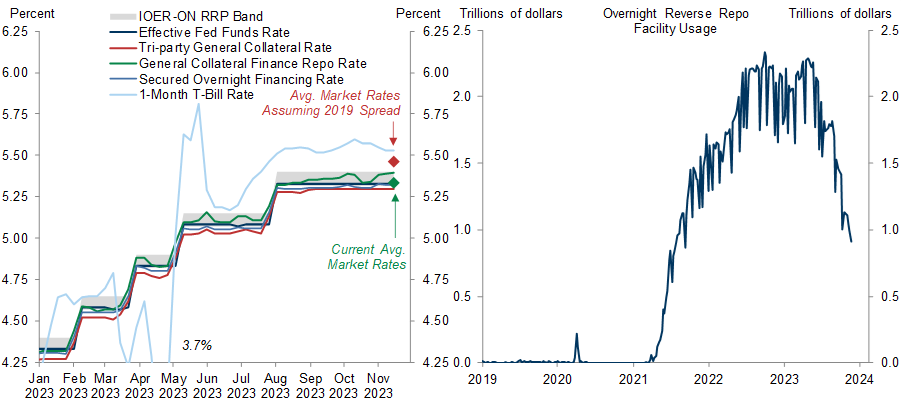

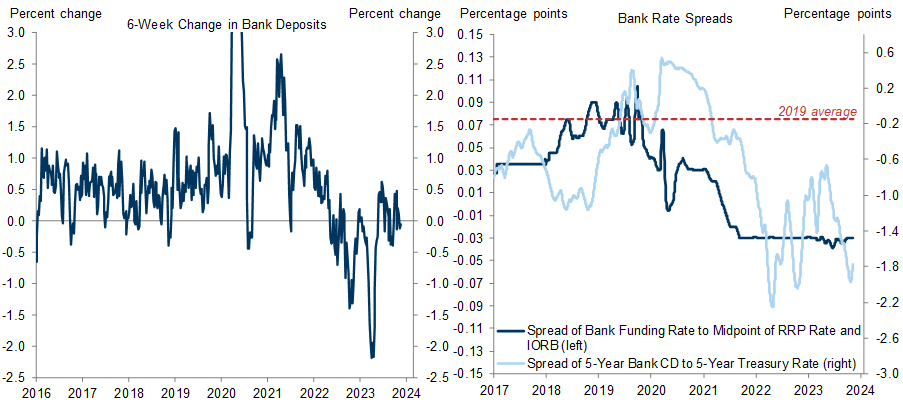

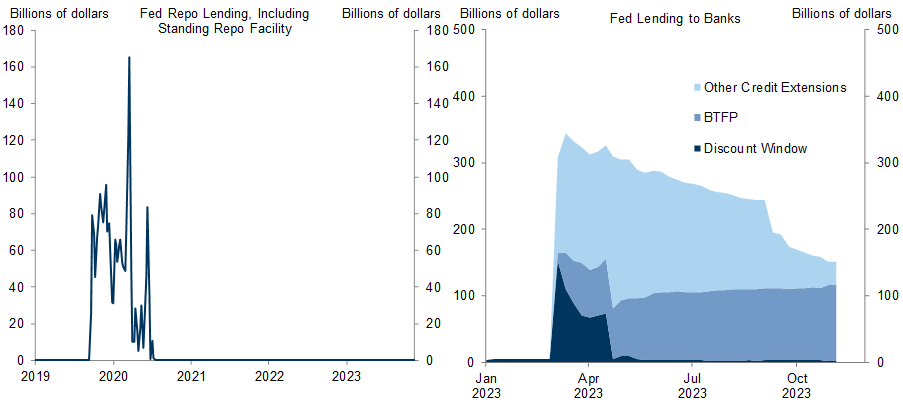

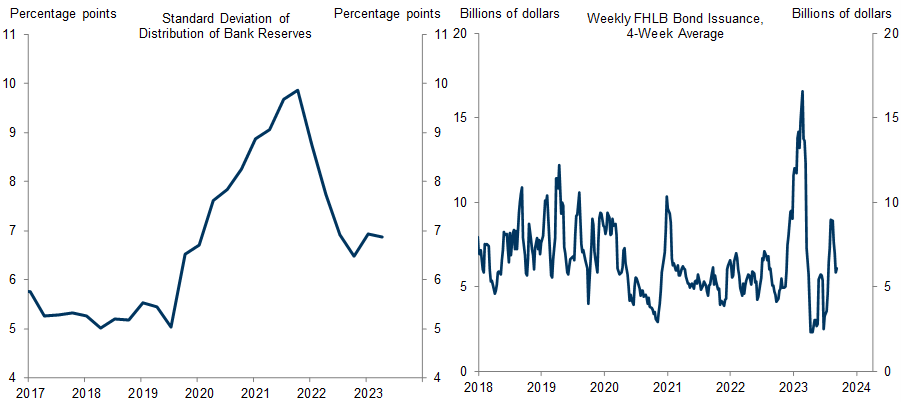

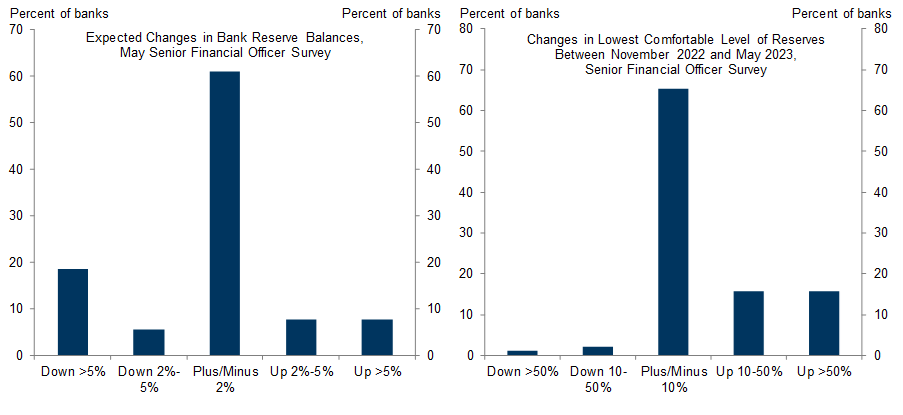

There is substantial uncertainty over how conditions in money markets will evolve as runoff continues. We therefore introduce a number of indicators to monitor how conditions are evolving in short-term funding markets. These indicators suggest that liquidity currently remains abundant, though we expect them to signal pockets of scarcity in mid-2024.

When Will Balance Sheet Runoff End and How Will the Fed Know When to Stop?

The evolution of balance sheet runoff and our projection for the stopping point

Monitoring conditions in funding markets

Conditions in overall funding markets

Exhibit 2: Key Money Market Rates Remain Close to the Lower End of the IORB-RRP Band, Indicating That Liquidity Remains Plentiful; Short-Term Treasury Rates Remain Above Repo Rates, Which Should Push Money Market Funds to Continue Shifting Assets from the RRP Facility to Treasuries

Conditions for banks

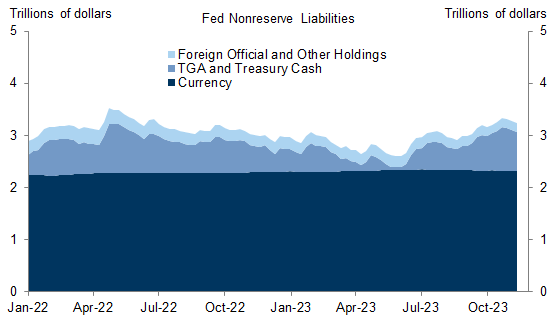

The evolution of non-reserve liabilities

Manuel Abecasis

Praveen Korapaty

- 1 ^ This simplified illustration ignores other changes that may affect banks and money market funds’ incentives for holding reserves and RRP balances, such as changes in interest rates and changes in the composition of bank deposits. Acharya and Rajan (2022), for example, argue that QE shifts the composition of bank funding toward more volatile uninsured demand deposits, which increases banks’ demand for reserves in order to ensure liquidity in the face of more volatile liabilities. Interest rates also change the optimal composition of bank funding—for example, time deposits have increased rapidly since the Fed started hiking, and banks may demand a different quantity of reserves to match these liabilities.

- 2 ^ The Fed’s balance sheet expanded somewhat in response to the banking turmoil in March 2023 but resumed its decline after conditions in the banking sector stabilized in April.

- 3 ^ This should meaningfully slow the pace of Treasury runoff but have a more muted impact on the pace of MBS runoff, since higher mortgage rates have reduced mortgage prepayments substantially.

- 4 ^ Afonso, Gara, Domenico Giannone, Gabriele La Spada, and John C. Williams, “Scarce, Abundant, or Ample? A Time-Varying Model of the Reserve Demand Curve,” May 2022 (revised June 2023).

- 5 ^ Lopez-Salido, David, and Annette Vissing-Jorgensen, “Reserve Demand, Interest Rate Control, and Quantitative Tightening,” November 2021 (revised September 2023). We take the parameters in the paper and estimate the implied level of reserves using the latest data on deposits, which have declined somewhat since the authors published it in 2022. Their estimates imply that reserve balances equal to $2.6tn would roughly match money market conditions in September 2019 while reserve balances equal to $3.2tn would result in an IORB-fed funds spread of zero. The average of these two estimates is about $2.9tn, similar to our forecast for the stopping point.

- 6 ^ See Afonso, Gara, Gabriele La Spada, Thomas M. Mertens, and John C. Williams, “The Optimal Supply of Central Bank Reserves under Uncertainty,” November 2023.

- 7 ^ The SRF and discount window rates are currently set at 5.50%, 10bp above the IORB rate.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.