We wish all of our readers a happy, healthy, and prosperous 2024. In the last US Economics Analyst of the year, we discuss what we believe are the most important questions for 2024.

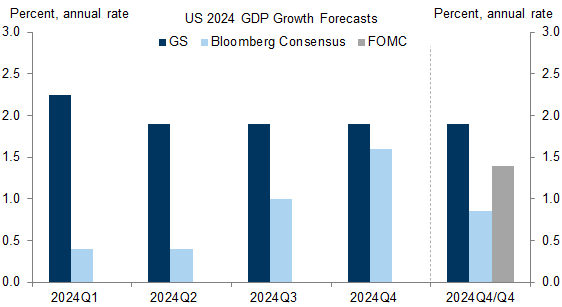

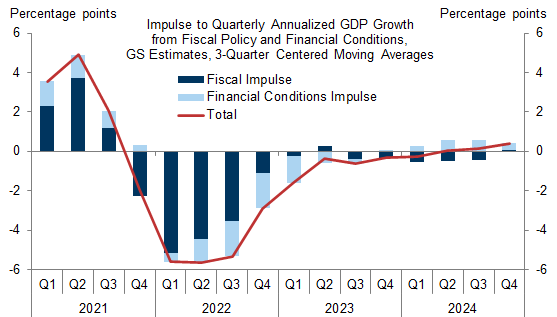

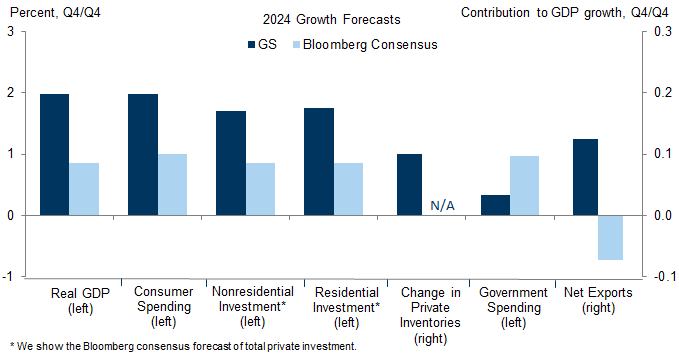

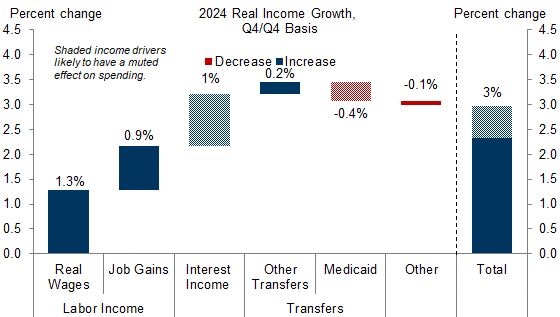

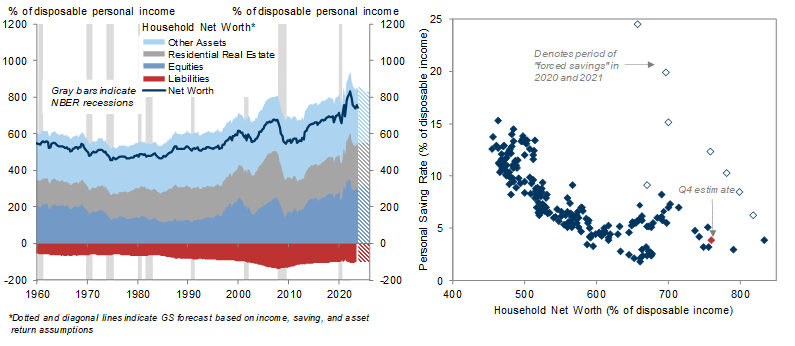

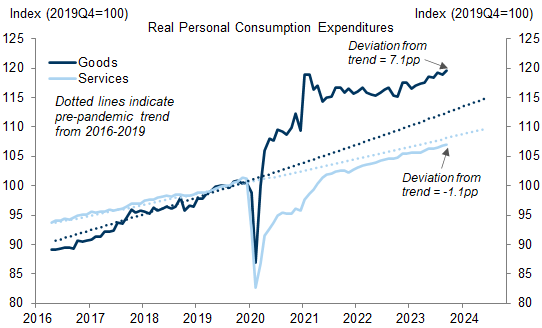

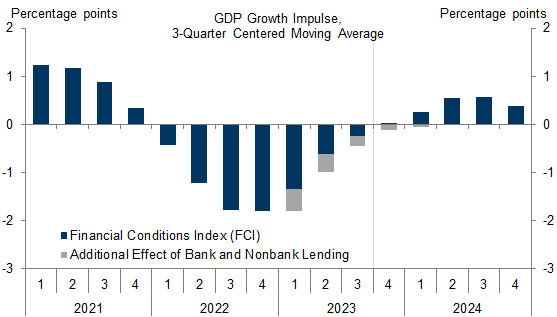

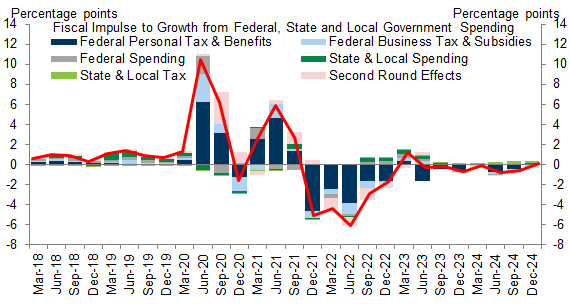

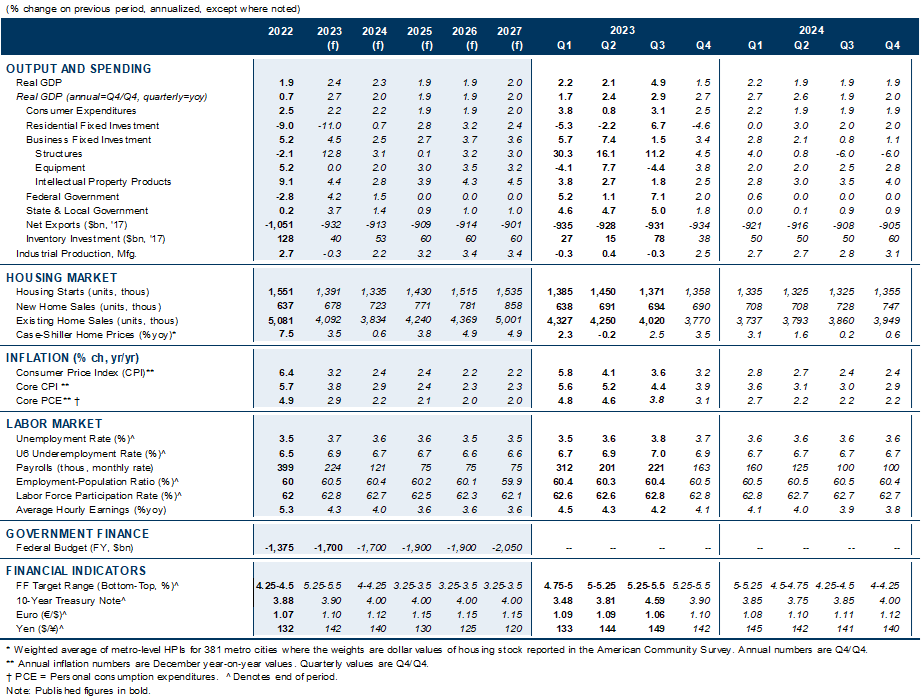

Our most out-of-consensus call for 2024 is our growth forecast. Our 2% forecast for 2024 Q4/Q4 GDP growth is well above consensus of 0.9% and the FOMC’s 1.4% forecast. This reflects our view that the growth impulses from changes in financial conditions and changes in fiscal policy should be modest and roughly neutral on net next year. It also reflects our forecast that consumer spending will easily beat expectations—we expect 2% growth vs. consensus of 1%—because real income should grow about 3% and household net worth is close to an all-time high.

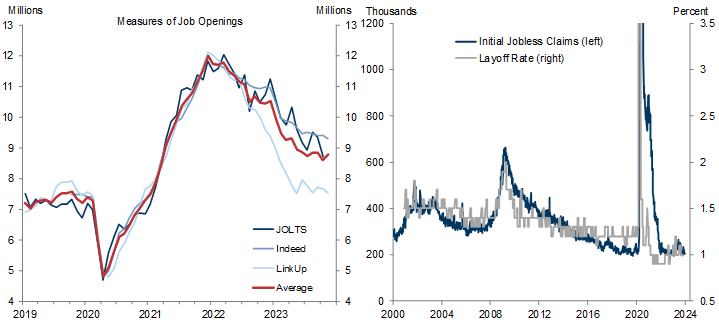

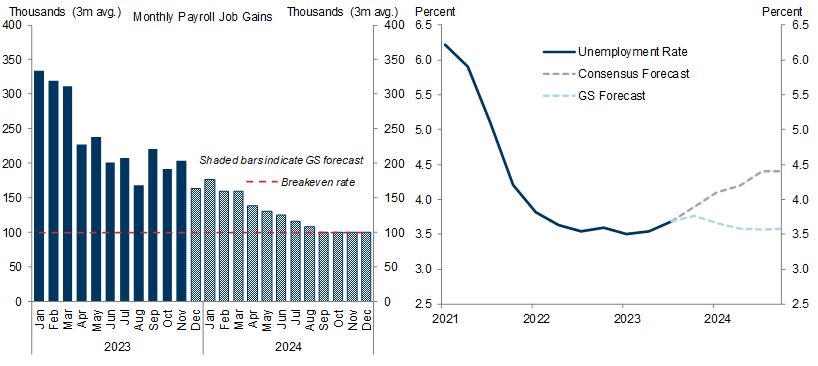

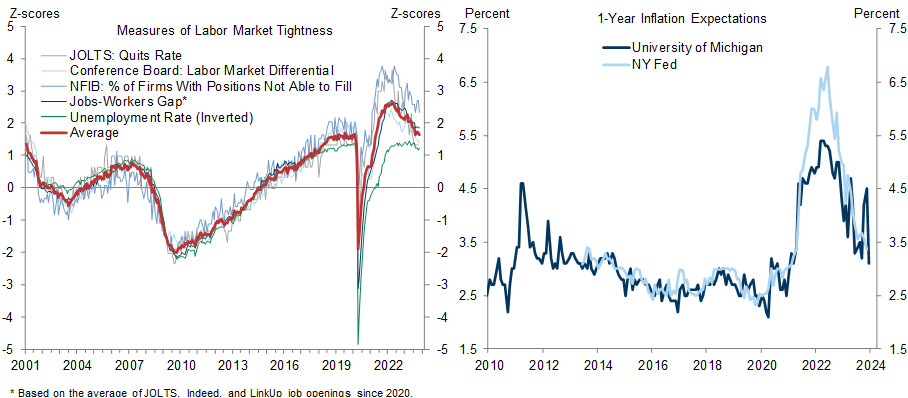

Consistent with our growth view, we expect the labor market to remain strong. The healthy starting point of still-high job openings and a low layoff rate coupled with fading recession fears should support steady job gains in 2024 at a rate that gradually converges over the year to the current breakeven pace of about 100k. This should keep the unemployment rate low at around 3.6%.

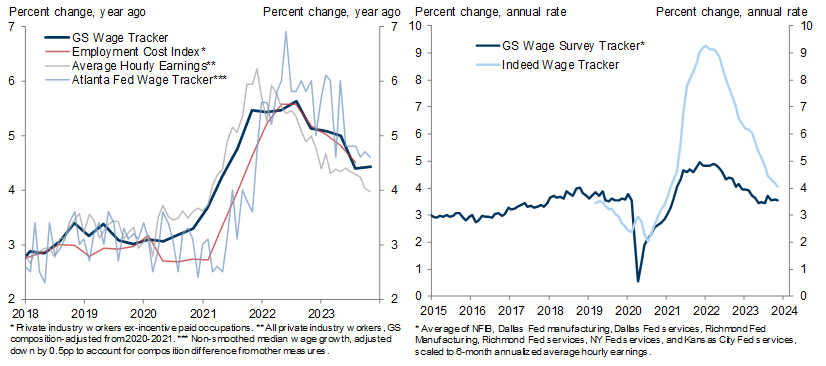

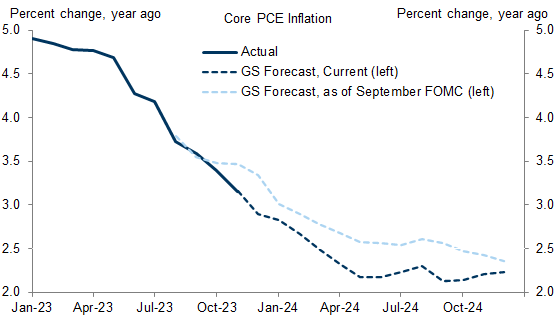

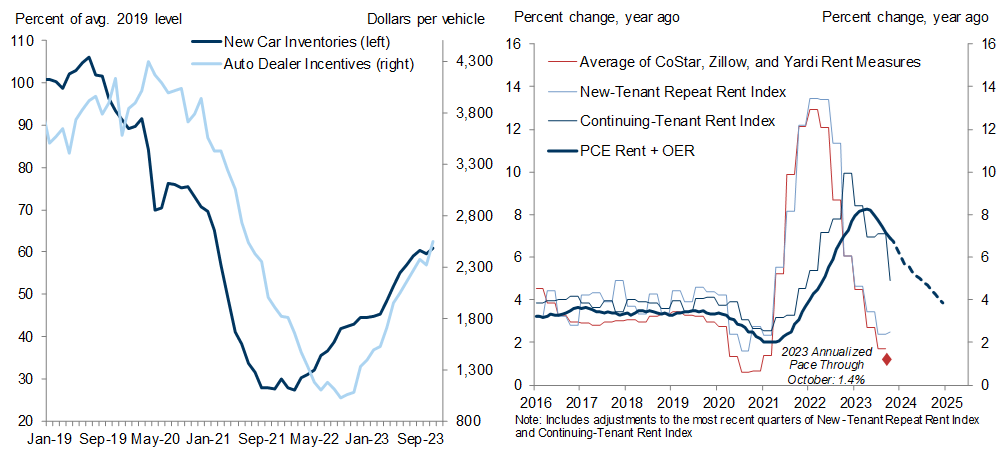

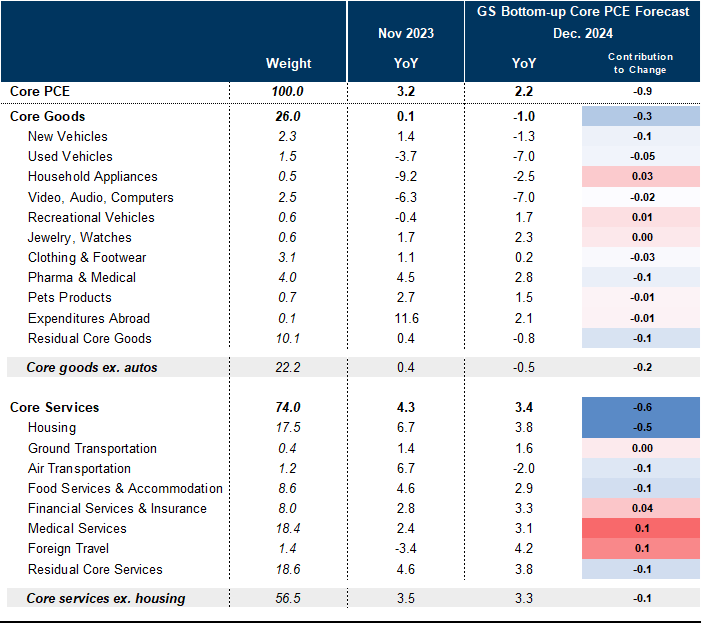

Wage growth and inflation should fall to roughly target-compatible levels in 2024. The main drivers of high wage growth over the last two years—extreme labor market overheating and big inflation shocks that sparked demands for larger cost-of-living adjustments—are now behind us. As a result, wage growth should keep falling toward the 3.5% pace we estimate is compatible with 2% inflation. Core PCE inflation slowed sharply in 2023H2 and appears on track to fall into the low 2s on a year-on-year basis by spring. We expect further rebalancing in the auto and housing rental markets to leave the year-on-year rate at 2.2% at the end of 2024, undershooting the FOMC’s 2.4% forecast, and we see a reasonable chance that it could fall below 2%.

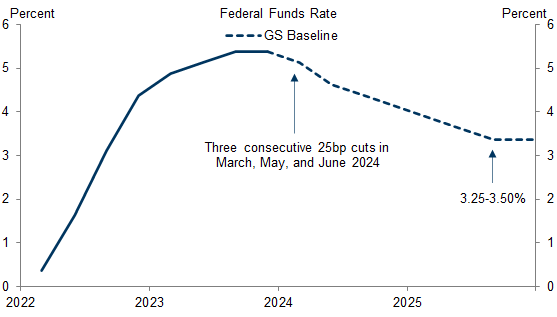

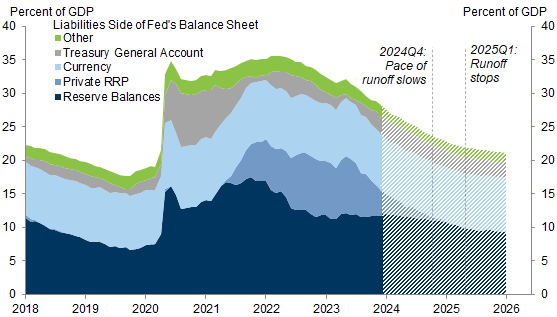

The rapid decline in inflation is likely to lead the FOMC to cut early and fast to reset the policy rate from a level that most participants will likely soon see as far offside. We expect three consecutive 25bp cuts in March, May, and June, followed by one cut per quarter until the funds rate reaches 3.25-3.5% in 2025Q3. Our forecast implies 5 cuts in 2024 and 3 more cuts in 2025. We also expect the Fed to slow balance sheet runoff in 2024Q4 and to end it fully in 2025Q1.

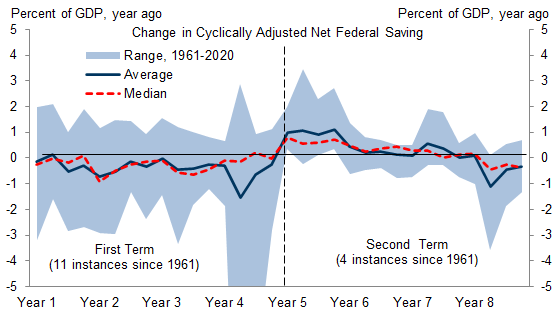

Fiscal policy is very unlikely to become more stimulative ahead of the election. In fact, we see downside risk to government spending from automatic spending cuts that will take effect in May if Congress continues to avoid government shutdowns by passing temporary extensions instead of full-year spending bills. The cuts would reduce funding by around 2% (0.4% of GDP).

10 Questions for 2024

Exhibit 14: We Are Confident That Further Disinflation Is in the Pipeline as Auto Inventories Recover and the Official Shelter Inflation Data Gradually Catch Down to Leading Indicators of Market Rent Inflation

David Mericle

Alec Phillips

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.