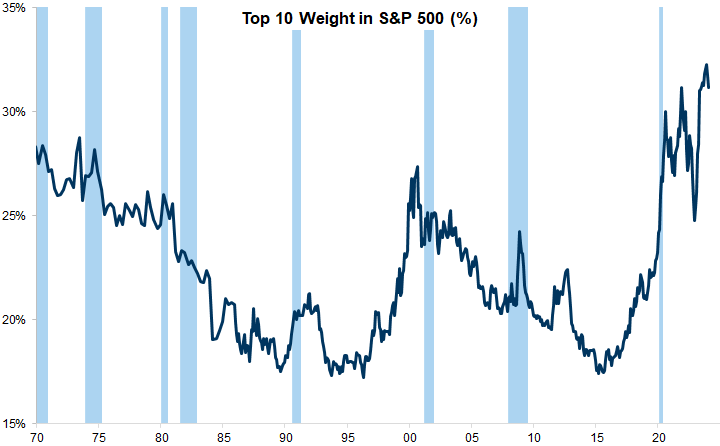

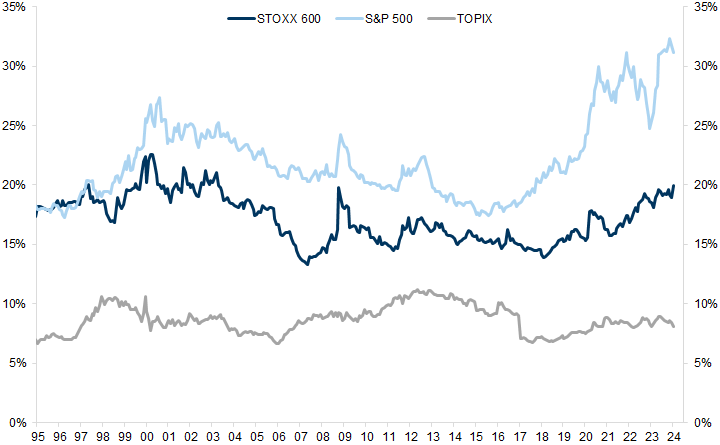

Stock market concentration has increased dramatically and has taken three broad forms: the rise in the share of the US equity market in the world, the rise in the share of the technology sector, and the rise in the dominance of the biggest companies in most regions.

But, does it really matter for investors that markets have become more concentrated and what, if anything, can they do about it? In this piece we look at each of these areas of increased market concentration, place them in historical context, and look at the implications and possible investment strategies to hedge concentration risk.

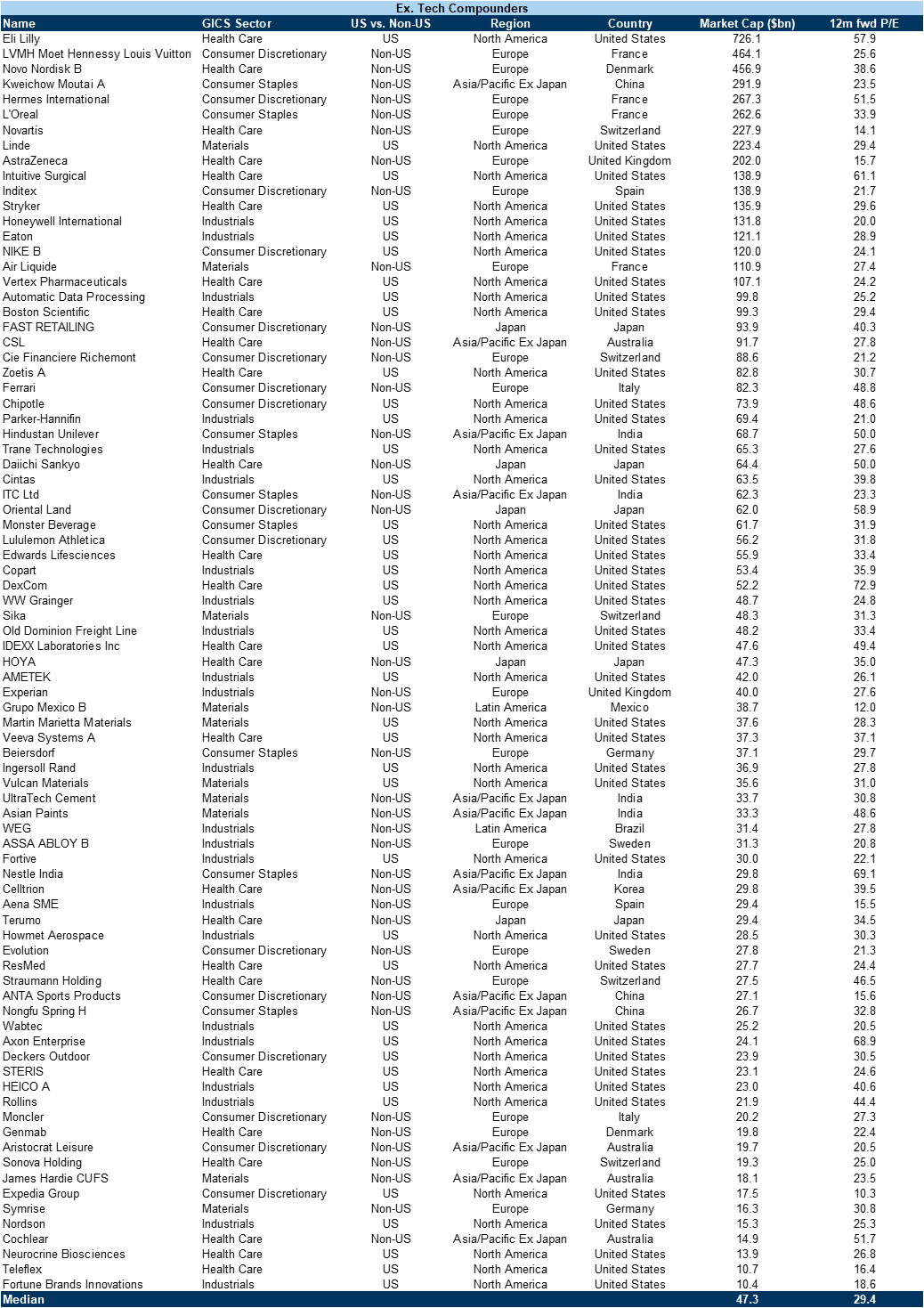

Market dominance is not unprecedented and is only a problem if it is not supported by fundamentals. That said, at the stock level in particular, dominant companies rarely stay the best performers over long periods of time. We therefore examine strategies to diversify. We recommend a more diversified geographical exposure. We identify a group of Global Ex Technology Compounders (the ETCs) and selected value compounders.

Concentration Consternation

At the market level: the rise in the weight of the US in global stock markets.

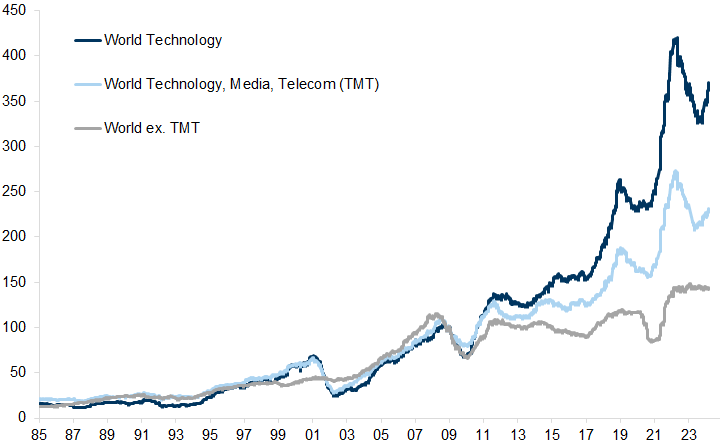

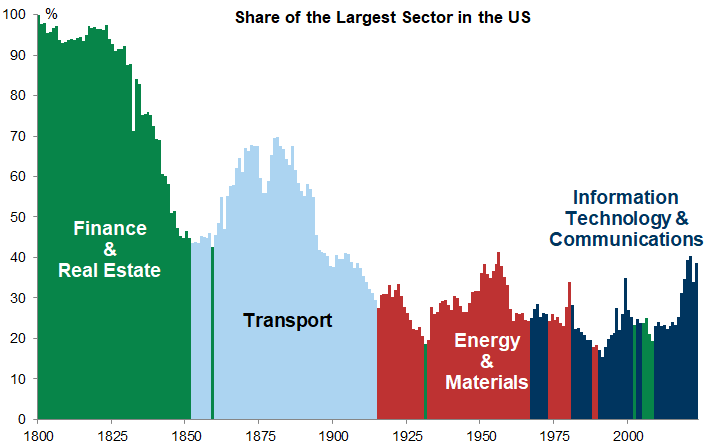

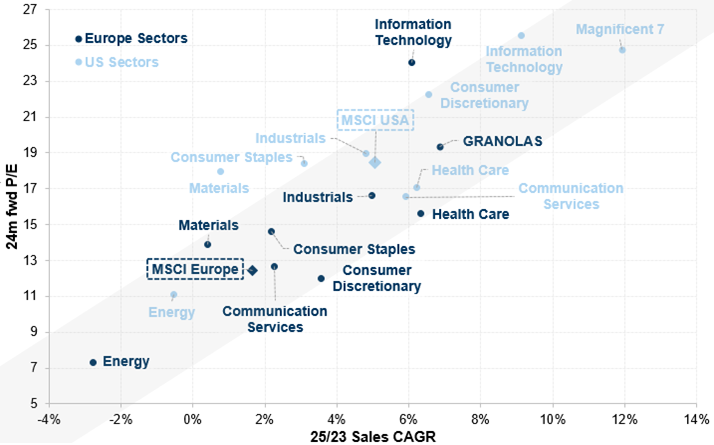

At the sector level: the rise in the weight of the technology sector within the US, in particular.

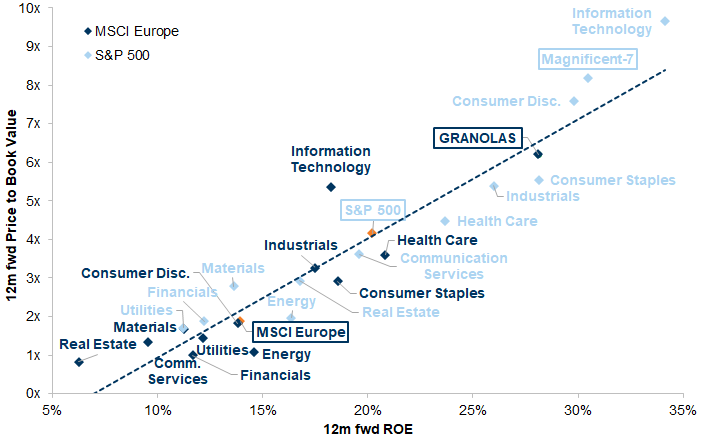

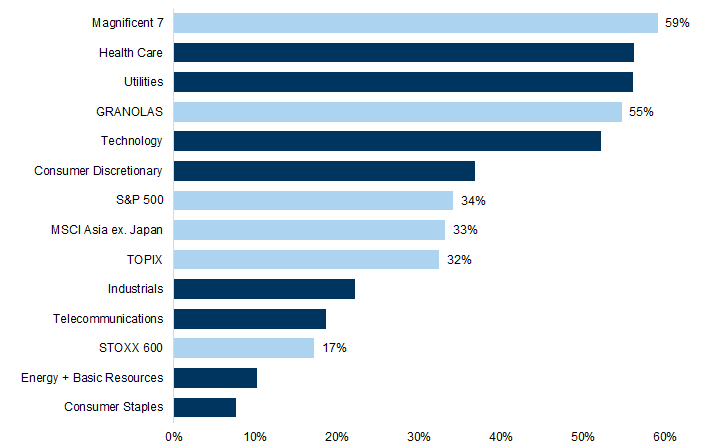

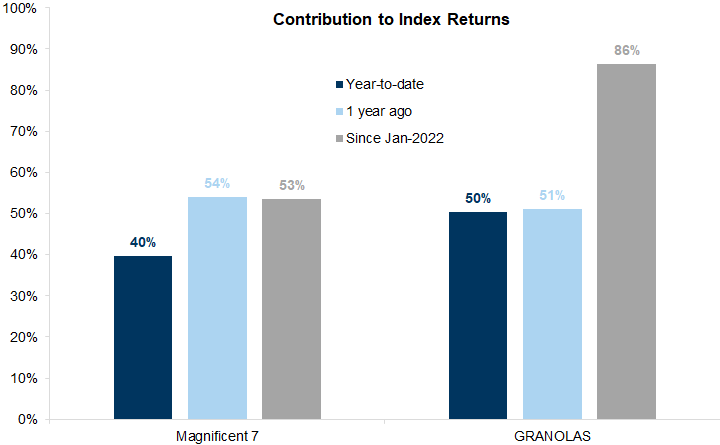

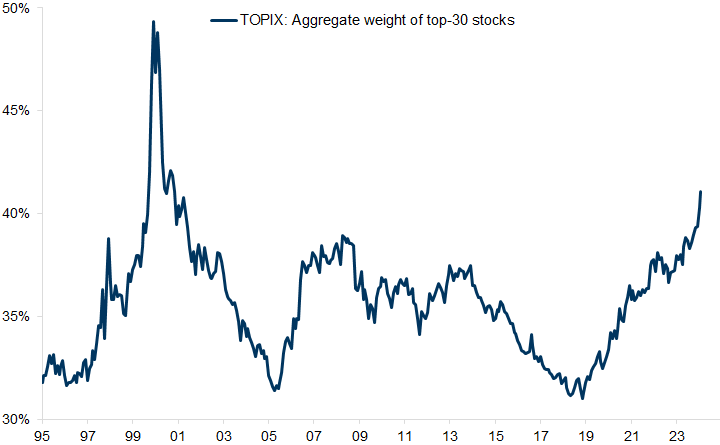

At the stock level: the increased dominance of the so-called Magnificent 7 in the US, the GRANOLAS in Europe, and the top 30 stocks in Japan.

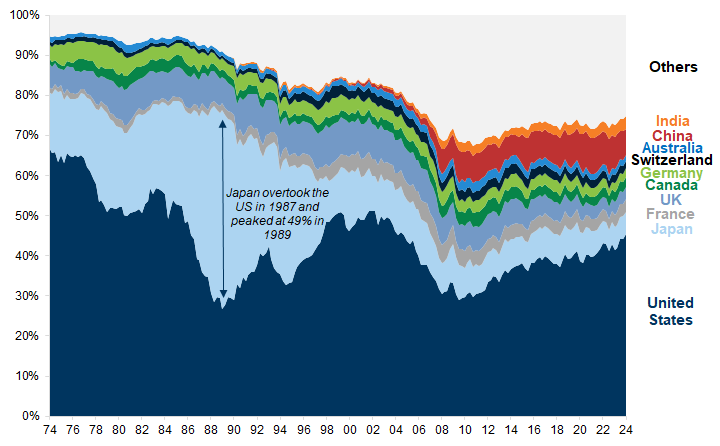

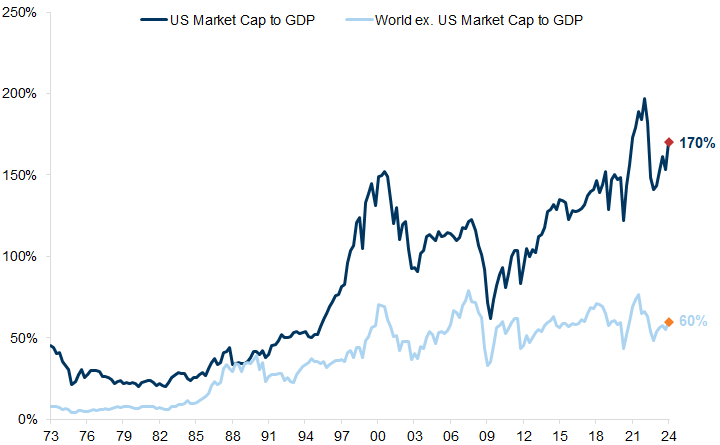

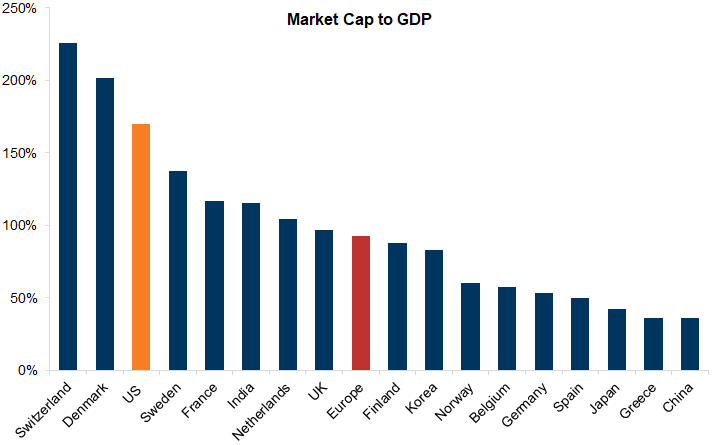

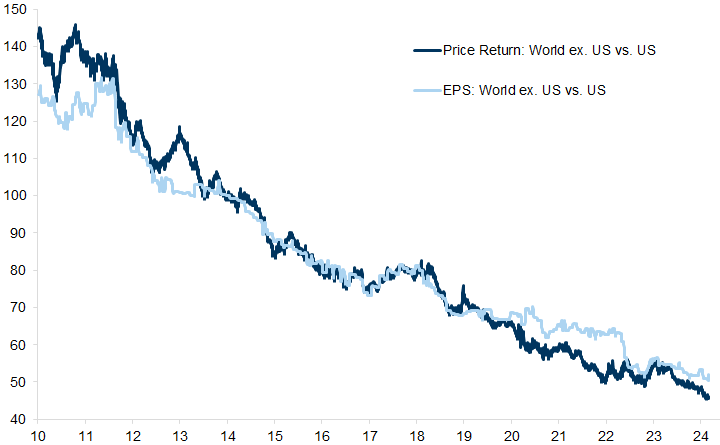

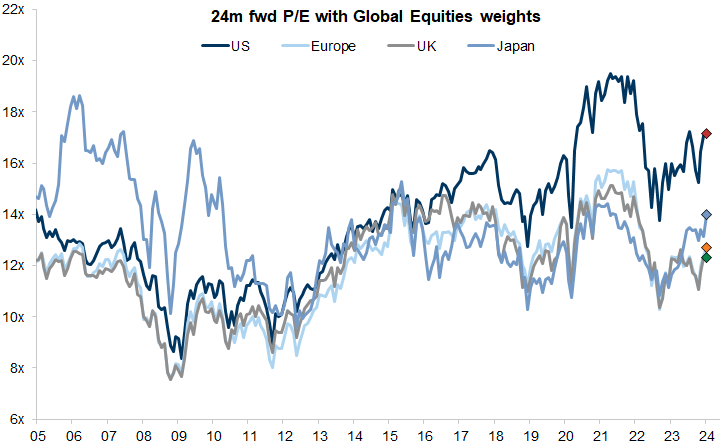

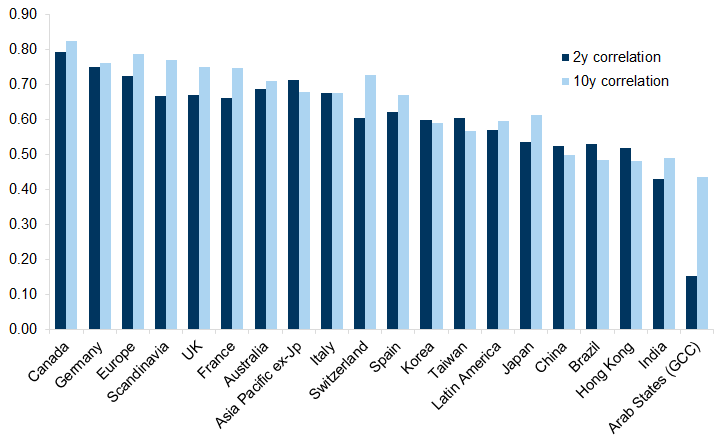

1. Market concentration by country: US equity market hegemony

Why has the US outperformed, and is this a problem?

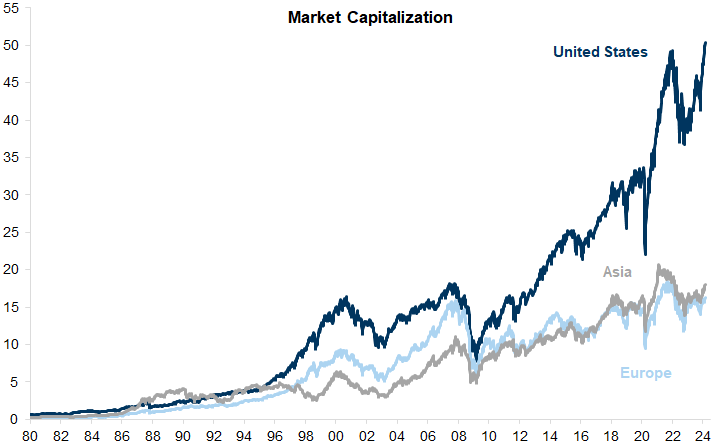

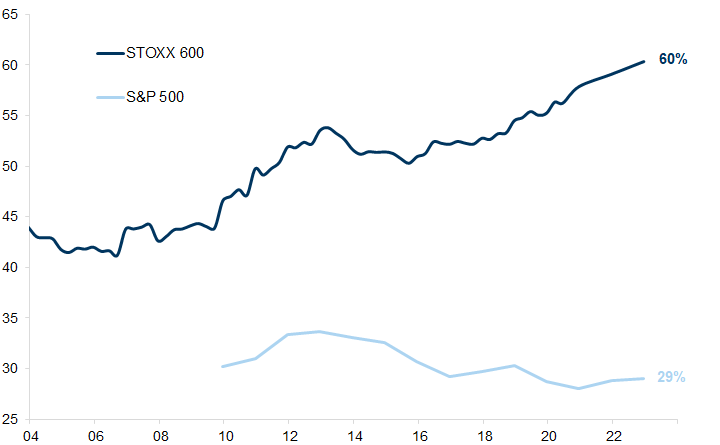

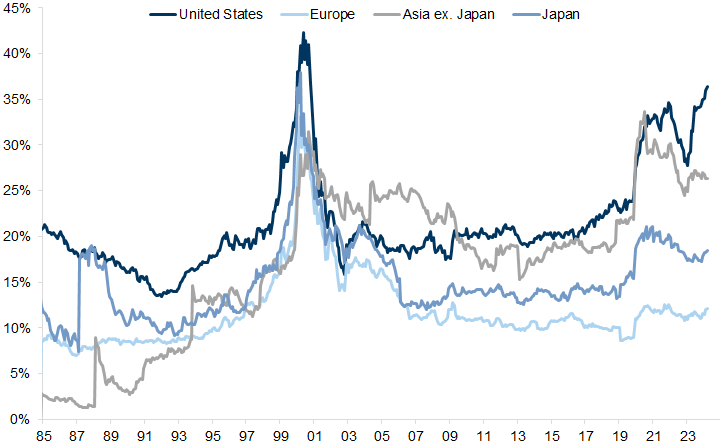

The reinvestment rate of companies in the US stock market is higher than in most other markets. The ability and willingness to reinvest at a high rate in companies that are growing is contributing to the relative lead of the US market. This is particularly so in the technology sector. The US also benefits, relative to other markets, from having comprehensive and unique support ecosystems, including collaboration with universities and the government, incubator and accelerator funds, VC and PE funds.

The liquidity of the US stock market is much higher than for other markets, helping to reduce the risk premium. The US equity market is increasing its depth relative to other markets. Geopolitical concerns and government involvement has reduced global appetite in some emerging markets, and in particular in China. Meanwhile, Europe has much poorer liquidity than the US. The US has also attracted investment and companies as a result of government incentives, tariffs on imports and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The US economy is bigger and stronger than others and the growing trend towards US listings by foreign-based companies has added to this effect; it means that a growing part of the value of foreign-originated companies are represented in the US market. Furthermore, even if not listed in the US, many European and other companies have generally increased their exposure (and assets) in the US (Exhibit 7).

What should Investors do about it?

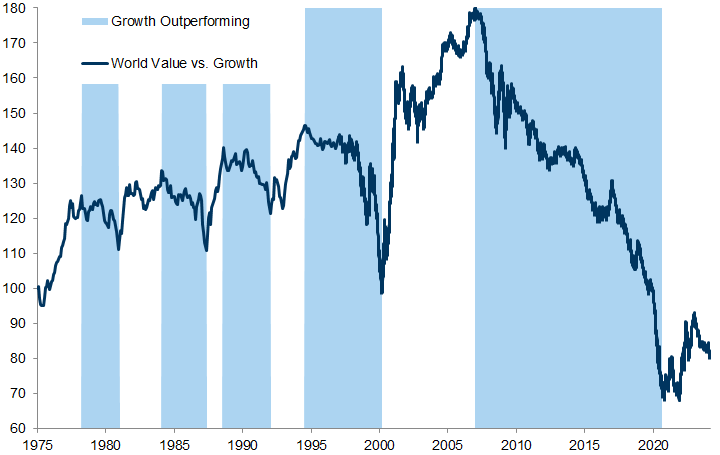

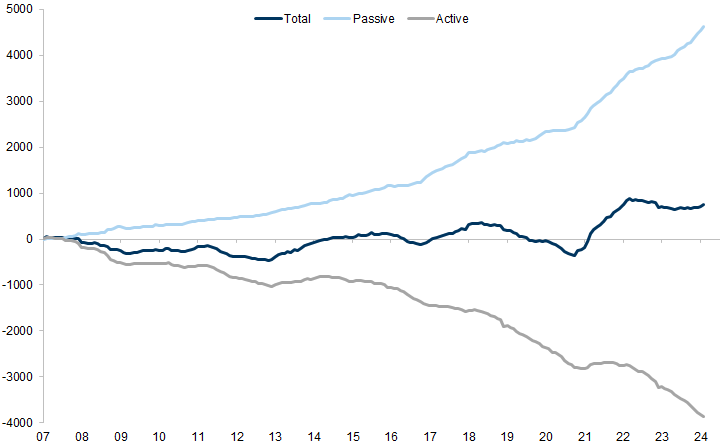

2. Market concentration by sector; the rise of Technology

What should Investors do about it?

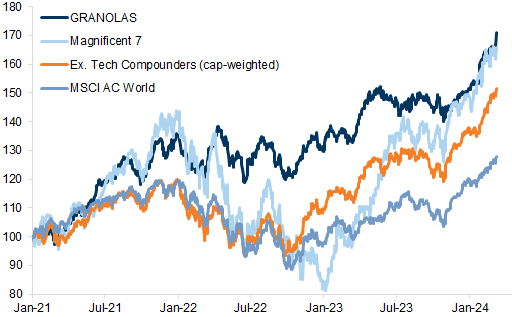

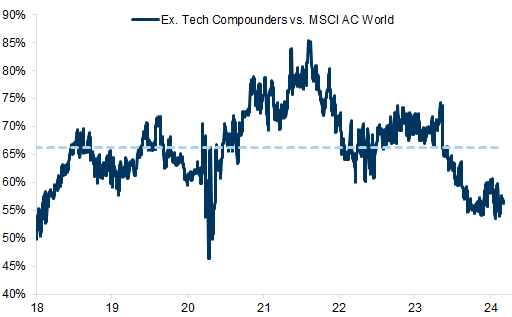

Exhibit 18: The Global Ex Tech Compounders (ETCs) have outperformed the global market over the past year...

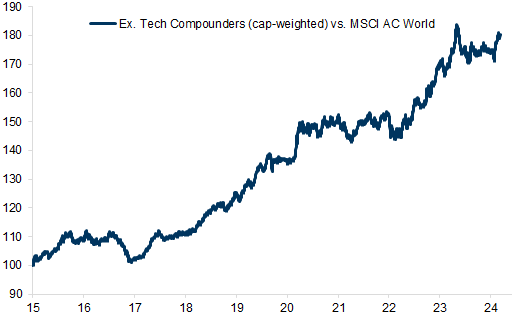

Exhibit 19: ...and since 2015

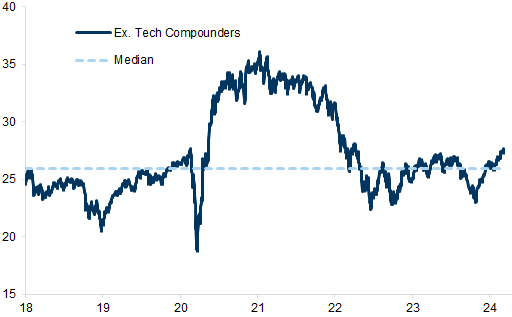

Exhibit 20: The valuation of our global ETCs list is in line with its average since 2016...

Exhibit 21: ...and the list trades at the lowest premium to the world stock market since 2018

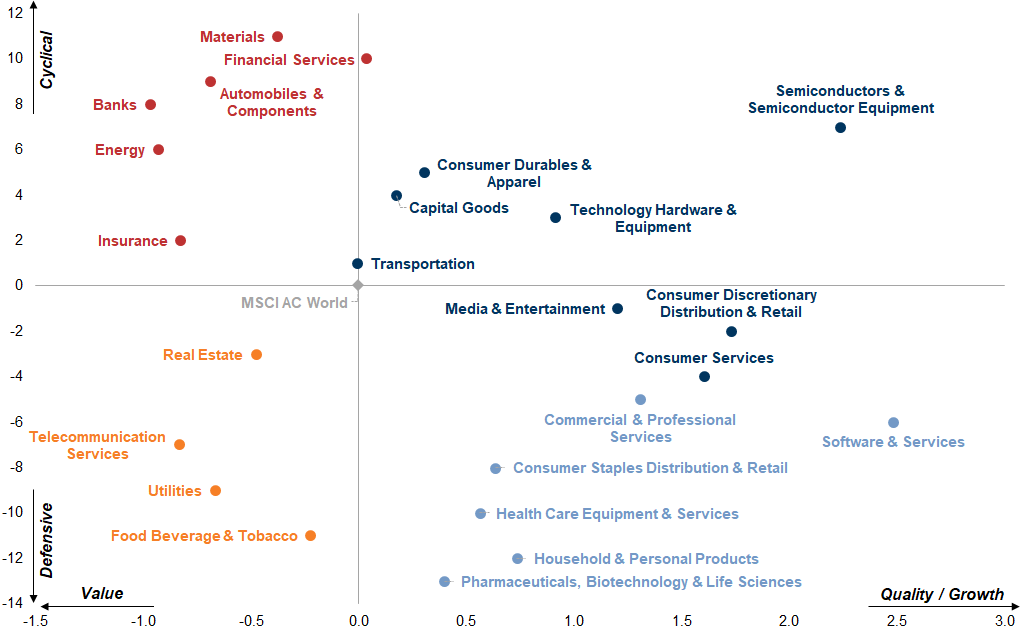

Exhibit 22: MSCI AC World exposure to Value/Growth/Cyclical/Defensive

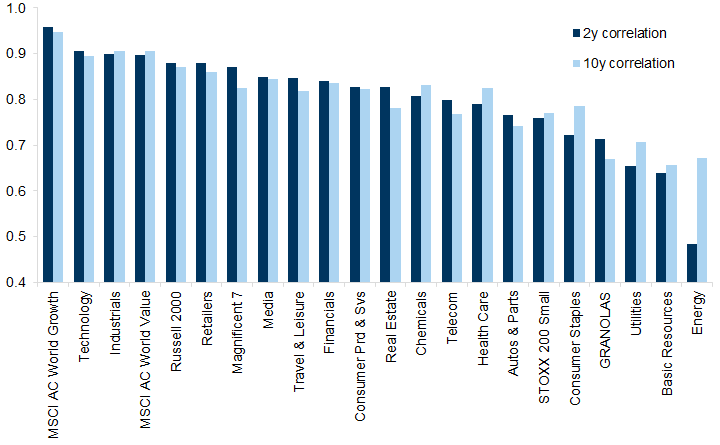

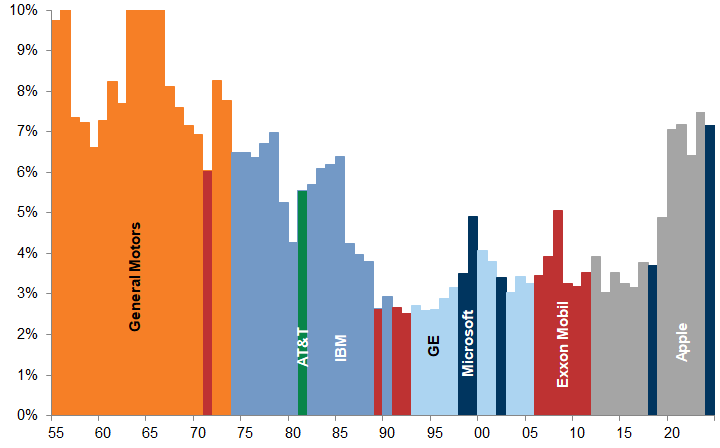

3. Concentration by stock; the growth of the Magnificent 7 and GRANOLAS

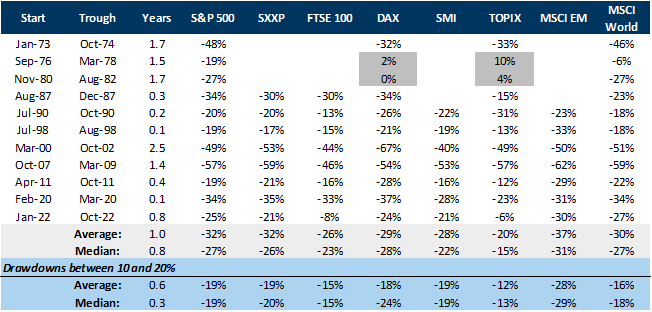

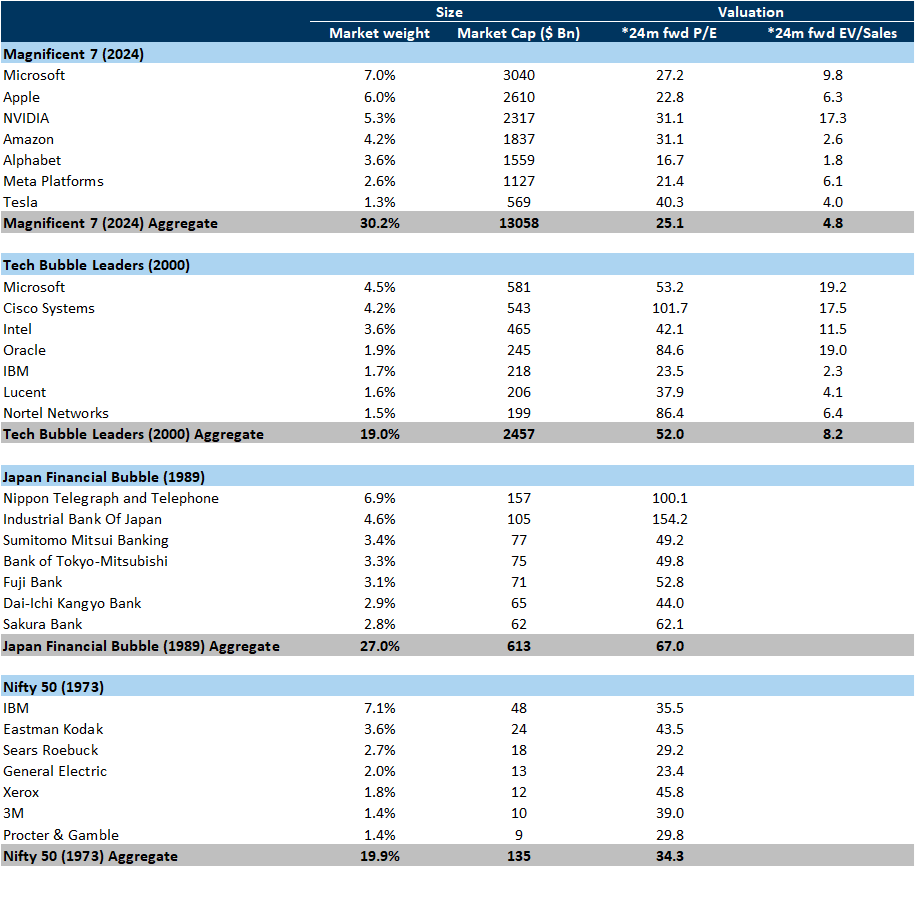

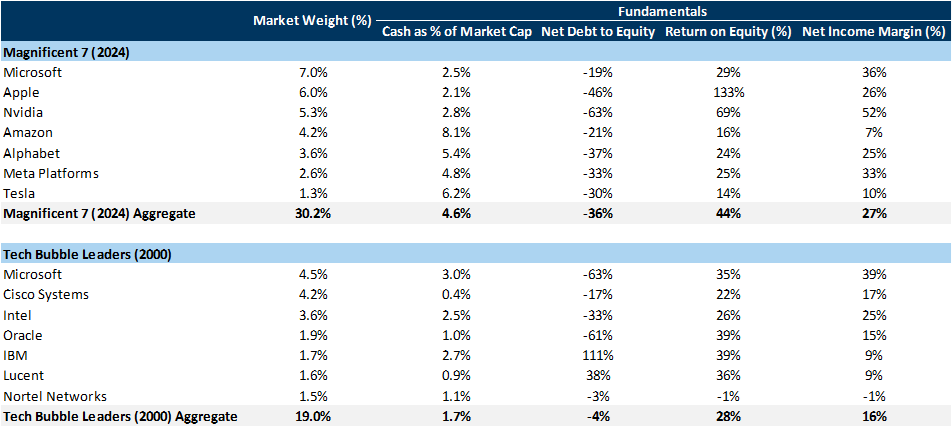

Does high stock market concentration reflect a bubble?

Exhibit 27: Dominant companies today are not as expensive as those in previous ‘bubble’ periods in history

Is high stock concentration a big risk?

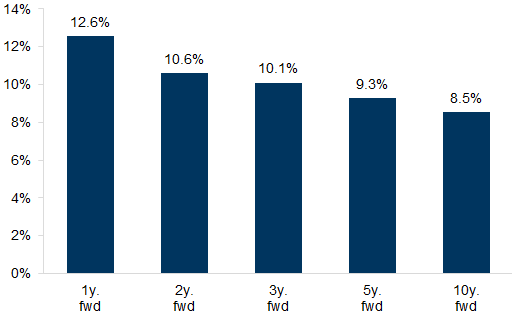

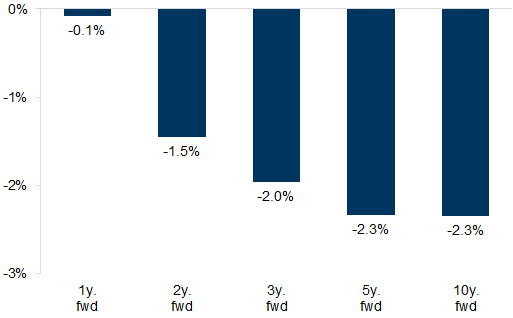

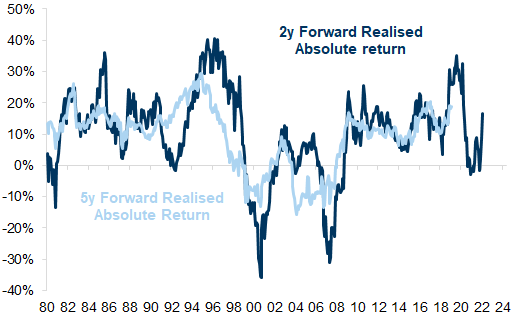

Exhibit 32: Absolute returns remain good for dominant companies...

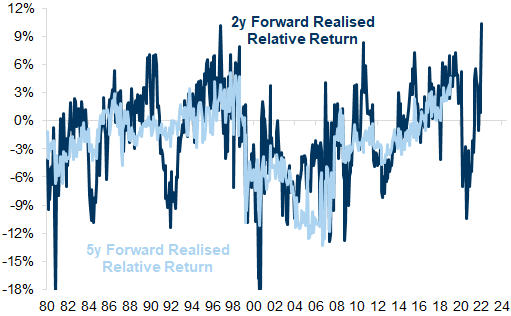

Exhibit 33: ...but they generally underperform (over the long run)

Exhibit 34: The current dominant group of companies has performed well in absolute terms

Exhibit 35: The current dominant group of companies has performed better in relative terms compared with dominant companies in the past

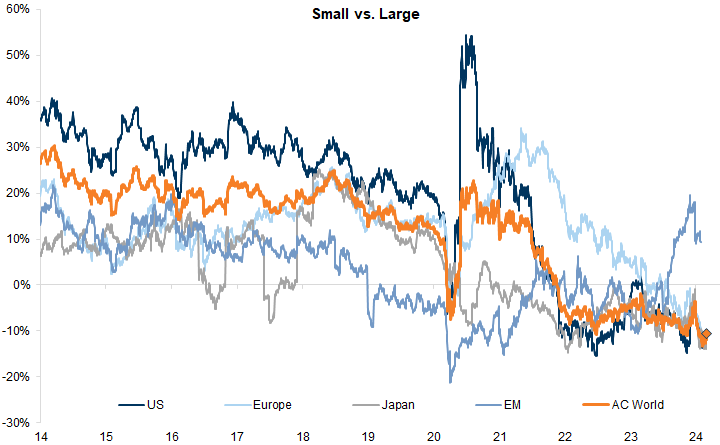

What should Investors do about it?

Defensive, strong balance sheet growth companies that are reinvesting and able to compound superior earnings growth - like the ETCs.

Mature companies that are cash-generative and are able to buy back shares and pay dividends.

Smaller cap companies with lower valuations (see, for example, US Macroscope: Low valuations and a healthy growth outlook signal more upside for small-caps).

Appendix

Constituents of MSCI AC World

Excludes GS Sell-rated companies

Large cap (Mkt Cap > $10bn)

High margins (EBITDA > 14%, EBIT > 12%, Net Income > 10%)

High profitability (ROE > 10%)

Strong balance sheets (ND/Equity < 75%, ND/EBITDA < 2x)

Volatility (5y Realized Vol < 50)

Growth prospects (sales > 4% and earnings > 8% 2y forward CAGR) and consistently grown their earnings over the past decade

Based on consensus estimates

- 1 ^ Bessembinder, Hendrik (Hank), Wealth Creation in the U.S. Public Stock Markets 1926 to 2019 (February 13, 2020). Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3537838 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3537838

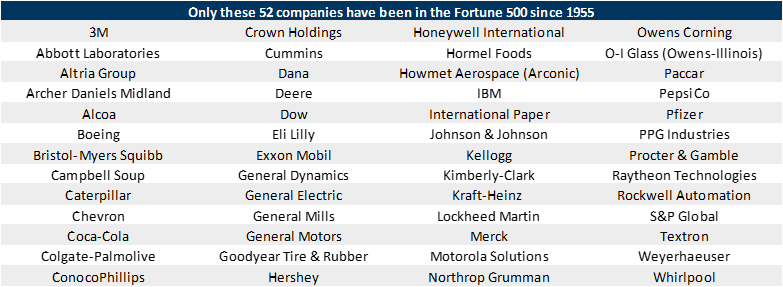

- 2 ^ https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/only-52-us-companies-have-been-on-the-fortune-500-since-1955-thanks-to-the-creative-destruction-that-fuels-economic-prosperity-2/

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.