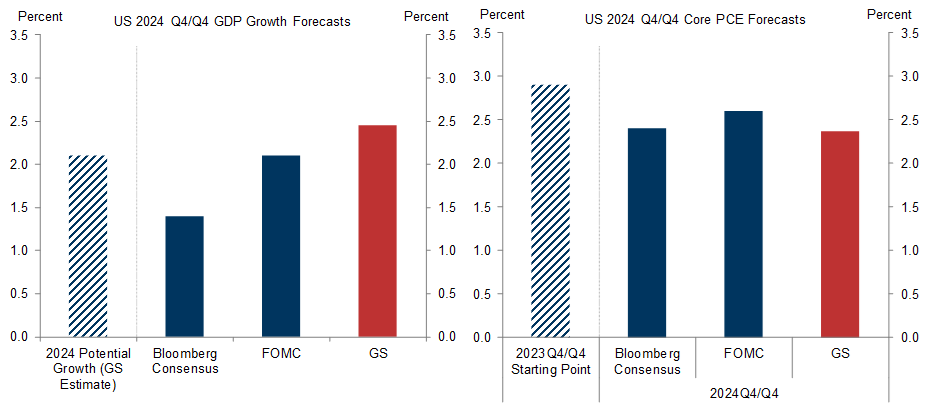

We expect much stronger GDP growth this year than consensus but nevertheless expect core PCE inflation to fall meaningfully, enough for the FOMC to cut three times starting in June. We are often asked whether these forecasts aren’t contradictory—won’t stronger growth prevent inflation from falling or even reignite it? We don’t think so, for two reasons.

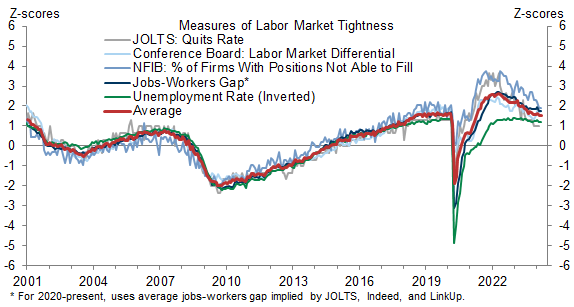

First, while our 2024 Q4/Q4 GDP growth forecast of +2.5% is well above consensus expectations of +1.4%, it is only moderately above our +2.1% estimate of potential GDP growth in 2024. We think that the supply-side potential of the economy is likely to continue growing somewhat faster than usual this year because elevated immigration is boosting labor force growth, which means that strong demand growth is unlikely to worsen the supply-demand balance by much, if at all. In fact, so far measures of labor market tightness have continued to fall or move sideways, not rise.

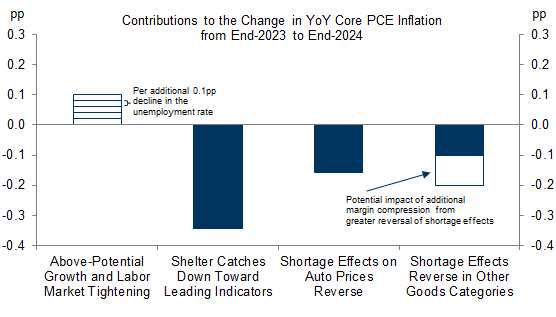

Second, standard estimates of the slope of the Phillips curve imply that even if the labor market were to retighten a bit, the impact on inflation would be quite small compared to the impact of the major disinflationary forces that we expect this year, continued catch-down of the very lagging official shelter inflation numbers toward the much lower leading indicators, and continued reversal of shortage effects that raised the prices of autos and other goods. While inflation forecasting is always subject to substantial uncertainty, these two fairly straightforward stories should make calling the direction of travel easier than usual this year.

Why We Can Have Both Strong Growth and Lower Inflation

David Mericle

- 1 ^ See, for example, a summary of our estimates from last cycle in “Lessons of the Low Inflation Years”, or Jonathon Hazell, Juan Herreño, Emi Nakamura, Jón Steinsson, “The Slope of the Phillips Curve: Evidence from U.S. States,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, August 2022. The slope of the Phillips curve is smaller in PCE terms than in CPI terms because much of the impact comes via the shelter category, which receives less weight in the core PCE index.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.