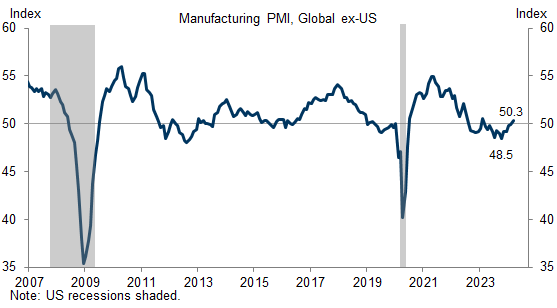

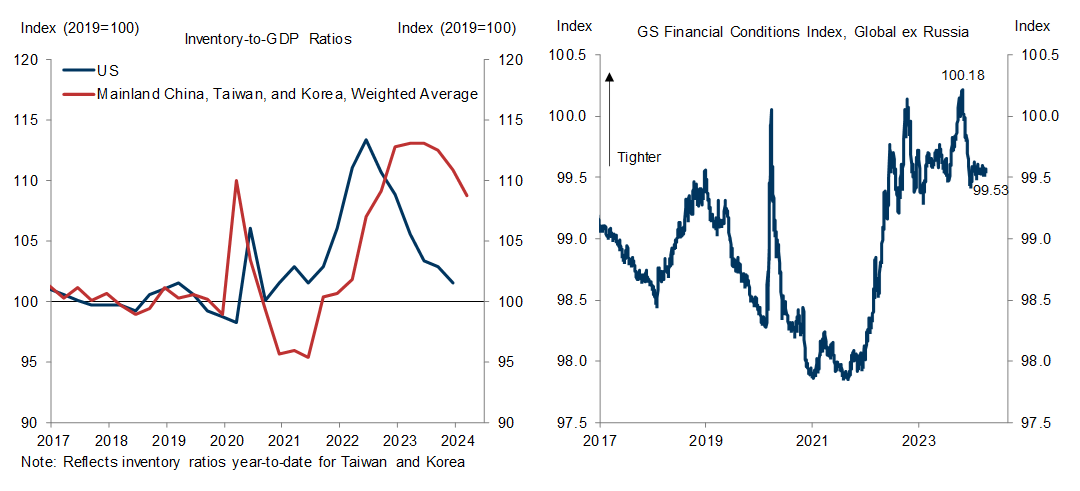

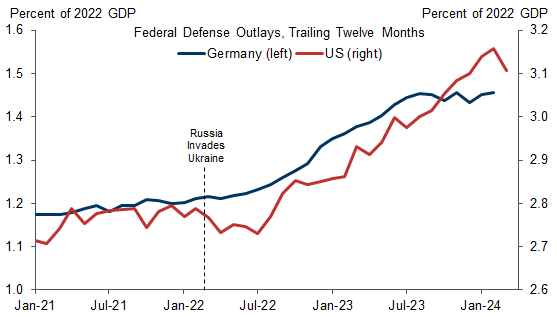

The global manufacturing cycle is picking up steam: foreign PMIs moved back above 50 in March, German industrial data has started to improve, and our China economists raised their GDP forecasts on the back of strong Q1 factory trends. This nascent rebound has multiple causes, including a waning drag from inventory drawdowns, the easing in global financial conditions, and increased spending on national defense. In this edition of the Analyst, we explore the implications of the foreign industrial pickup for US growth, employment, wage growth, and inflation.

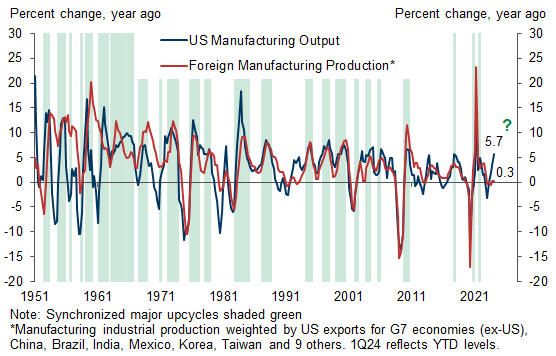

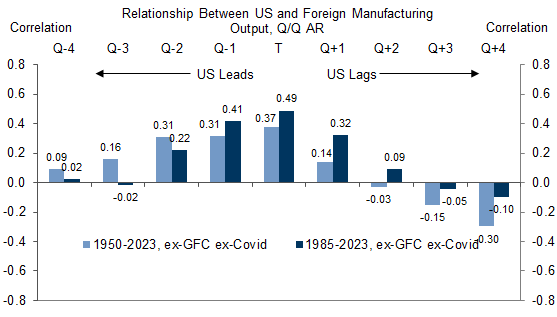

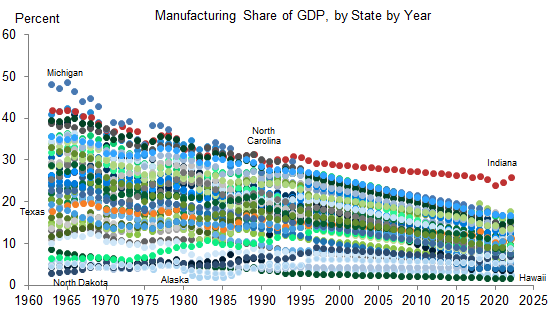

We construct time series of US and foreign industrial output over the last 75 years using quarterly manufacturing GDP in the US and the manufacturing subcomponent of industrial production across the G7 economies and 15 other countries. On this basis, US manufacturing output is currently rising at a fairly strong pace of 5.7% year-on-year, whereas the level of foreign factory output has picked up only marginally—up +0.3% year-on-year in Q1—after stagnating in 2022 and 2023. We also find that the two manufacturing series are positively but not perfectly correlated (correlations of +0.49 since 1985, qoq ar) and that the US manufacturing cycle tends to lead—though both series are influenced by shocks in the other.

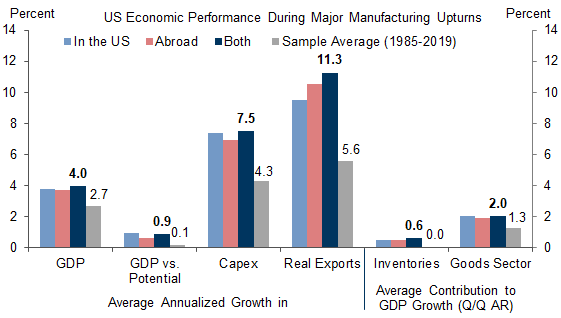

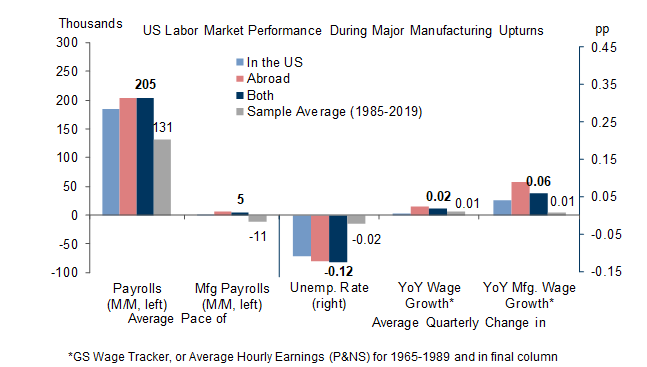

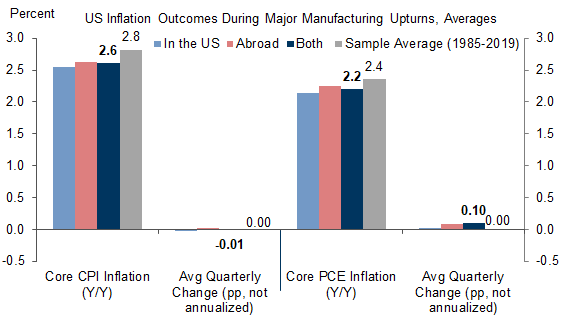

Unsurprisingly, we find that periods of strong US and foreign manufacturing growth are associated with strong US growth. Since 1985, US GDP growth has outpaced potential by 0.9pp in quarters with a synchronized major manufacturing upturn—defined as 5% or faster growth in US and foreign factory output. We find that the growth boost is roughly evenly split between inventories and final goods demand. The US labor market also tends to performs well, whereas the wage growth and inflation outcomes are inconsistent across episodes.

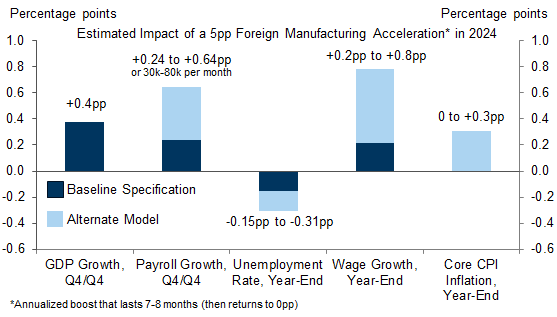

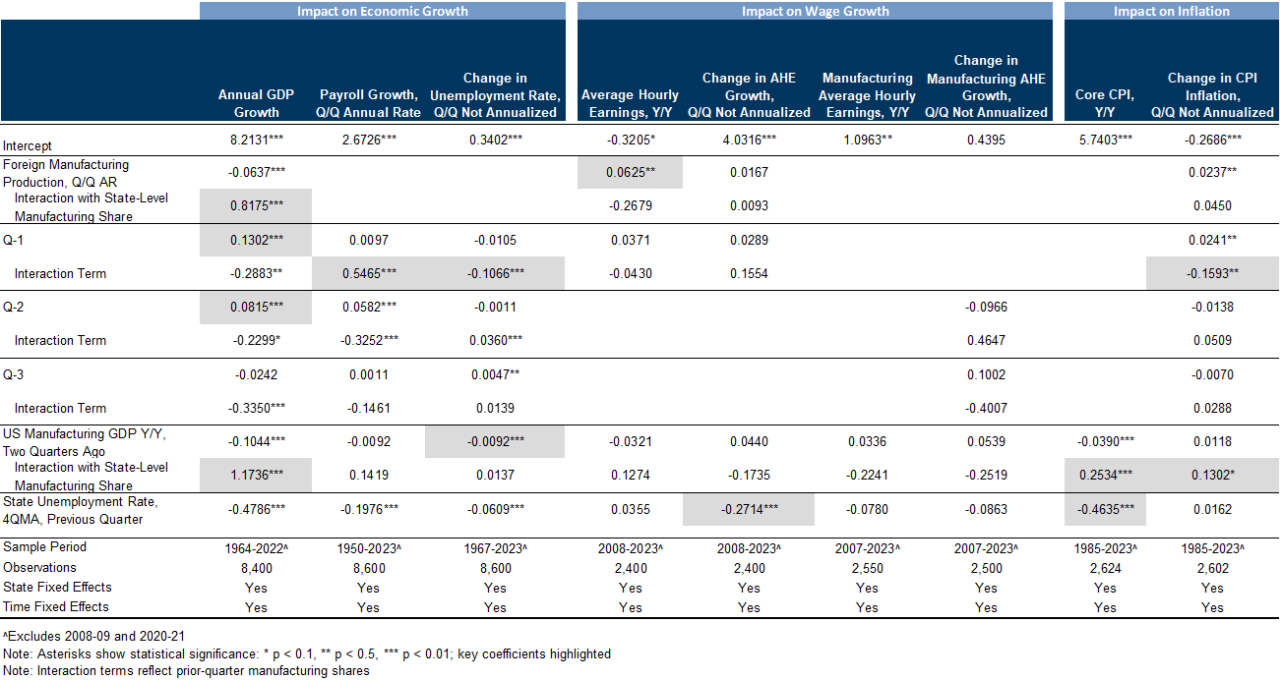

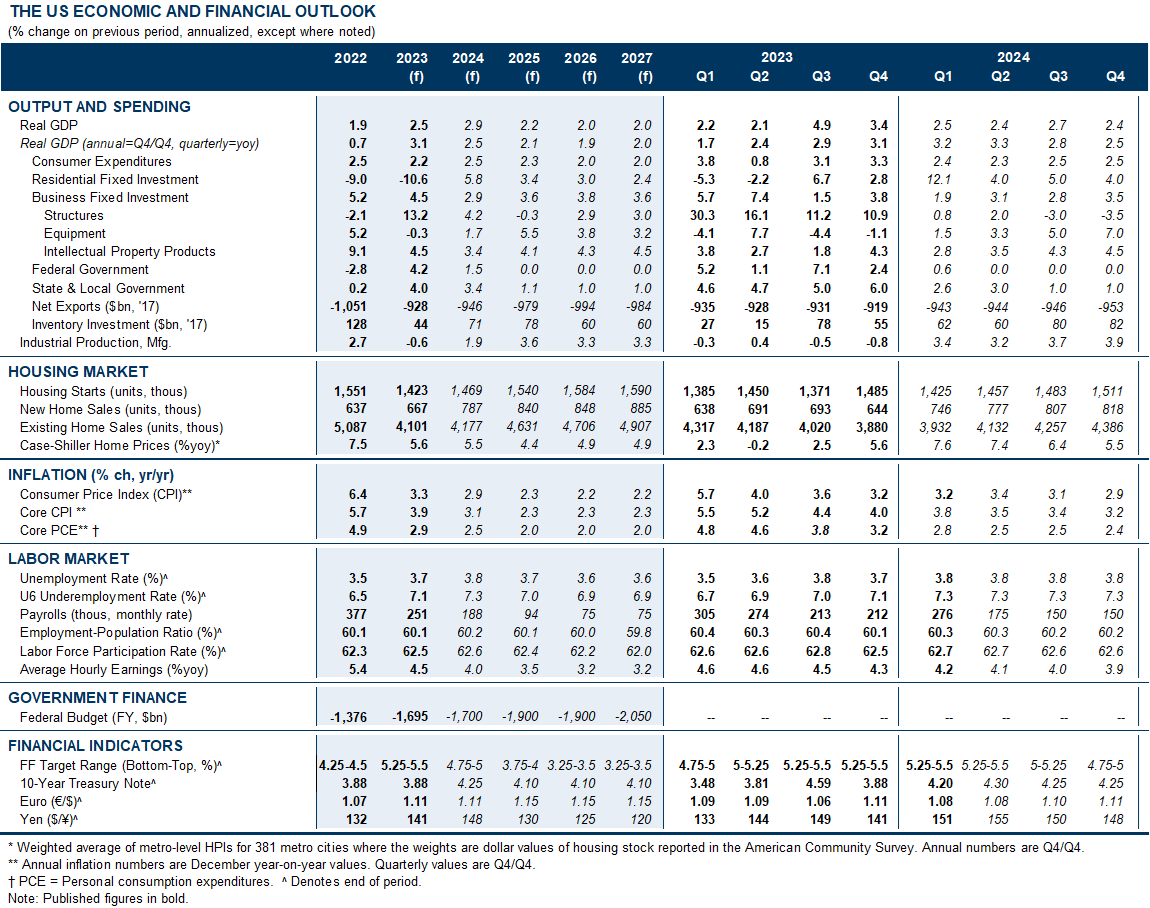

To estimate the causal effects, we model state-level economic outcomes—such as job growth or inflation—in a panel regression that exploits the variation in manufacturing GDP shares across states and across time. We also control for the state-level unemployment rate and for the trend in US manufacturing activity. Given the 10% GDP share of manufacturing in the US currently, we estimate that a “typical” rebound in global manufacturing activity would boost 2024 US GDP growth by 0.4pp (Q4/Q4 basis), boost nonfarm payroll growth by at least 30k per month, and would lower the unemployment rate by 0.15-0.3pp by year-end, other things equal. While such an acceleration abroad remains a risk rather than a baseline, these findings increase our conviction in our above-consensus GDP forecast for the year (+2.5% Q4/Q4 basis, vs. consensus +1.4%).

We estimate a more modest impact on 2024 wage growth, at +0.2pp under our preferred specification. The inflation effects are less straightforward, with an estimate range of zero to +0.3pp for year-end core CPI inflation (yoy). The mixed evidence on the inflation effects may reflect the tendency for periods of industrial strength to also exhibit above-average growth in manufacturing capacity. And for 2024 in particular, the continued labor supply tailwind from elevated immigration argues for a smaller-than-normal risk from wage growth or inflation spillovers.

Will Foreign Manufacturing Strength Boost US Growth and Inflation?

US and Global Manufacturing Cycles

Historical Performance of the US Economy During Manufacturing Booms

The Impact of the Foreign Factory Rebound on the US Economy

Implications for the US Outlook

Spencer Hill

Jessica Rindels

- 1 ^ For years in which quarterly data is unavailable, we interpolate annual manufacturing GDP using the manufacturing subcomponent of US industrial production.

- 2 ^ Mainland China, Brazil, India, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, Mexico, Chile, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Israel. For missing manufacturing production observations since 1980, we assume the growth rate of the world ex-US industrial production index produced by the Dallas Fed. For missing observations before 1980, we assume the manufacturing production growth rate across the UK, Germany, France, and Japan (weighted average; also includes mining production for the latter three countries).

- 3 ^ We apply fixed weights before 1976 due to data limitations.

- 4 ^ 2024 industrial production data for most countries is available for January and February but not for March.

- 5 ^ Granger causality test p-values of 0.001 on “foreign causes US” and 0.054 on “US causes foreign.”

- 6 ^ Specifically, we assume a downturn occurs whenever there are two consecutive quarters of negative quarter-on-quarter or year-on-year manufacturing output growth. We also assume that expansions must last most than one quarter—else the downturn continues. For example, on this basis, the US had a five-quarter manufacturing downturn from 1Q22 through 1Q23, as opposed to two separate two-quarter contractions interrupted by a one-quarter expansion in 3Q22.

- 7 ^ CBO measure.

- 8 ^ US GDP strength is even more outsized over the full sample (1950-2019), with GDP growth 1.9pp above potential, on average.

- 9 ^ The full sample period exhibits further strength in manufacturing payroll growth (39k on average, 41k above normal) and the unemployment rate (-0.17pp average quarterly decline).

- 10 ^ Over the full sample, both measures tend to rise at a marginal pace (of 5bp per quarter for core CPI inflation and 6bp per quarter for core PCE inflation).

- 11 ^ We allow for up to three quarterly lags on foreign manufacturing growth (qoq ar) and its interaction term, we include time and state fixed effects in each specification, and we exclude 2008-09 and 2020-21 because the Lehman and Covid shocks likely dwarfed the impact of exogenous changes in foreign factory activity in those quarters. We drop contemporaneous variables with negative (and likely spurious) coefficients, negative coefficients on the wage growth and inflation variables in their "levels" specifications, and several statistically insignificant variables with counterintuitive signs.

- 12 ^ Or 7-8 months. This is the average duration of synchronized major manufacturing upcycles as discussed in the previous sections (the US is already in a major upcycle, according to the classification criteria.)

- 13 ^ Indeed, the implausibly high payroll sensitivity in some specifications likely reflects reverse causality—strong US jobs growth tends to encourage stronger factory output abroad via the expected demand channel, and US job growth also correlates with other factors that likely encourage the same (e,g, US retail sales growth, financial conditions, business demand for capex, inventories, and intermediate inputs).

- 14 ^ On the other hand, because we are controlling for the unemployment rate in the prior period, inflation could receive a second-round boost from faster job growth—this would be additive to the above estimates.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.