The neutral real rate (r*) – the equilibrium real policy rate that is neither stimulatory nor contractionary, consistent with output at potential and stable inflation – is an important anchor for both monetary policy and financial markets.

In the years leading up to the 2020 Covid pandemic, there was a consensus among investors, policymakers, and academic economists that neutral rates in the US and other major advanced economies had fallen significantly. We were sceptical of this view – arguing that it exaggerated the likely decline in r* – and more recent estimates point to a higher level of neutral rates in the US and other major advanced economies in the aftermath of the pandemic.

While there has been significant research on developments in r* in major advanced economies, there has been less focus on neutral rates in other economies. In this piece, we use market-based estimates of r* for 12 developed (DM) economies and 24 emerging (EM) economies to explore developments in and the drivers of cross-country differences in r*. We find the following:

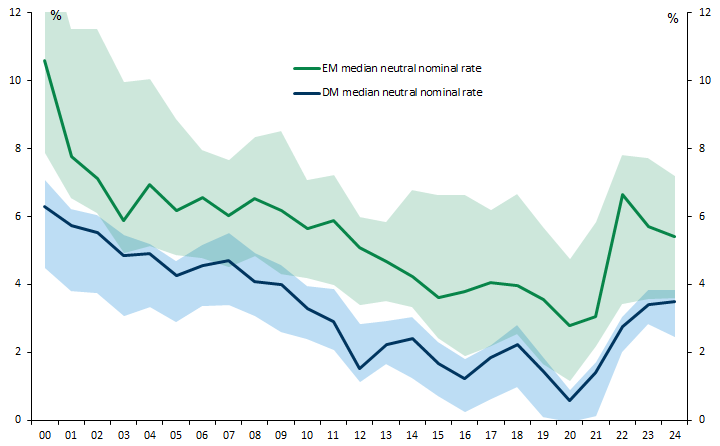

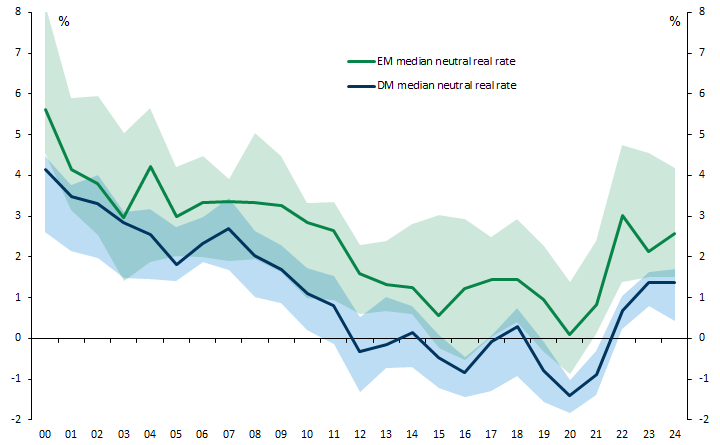

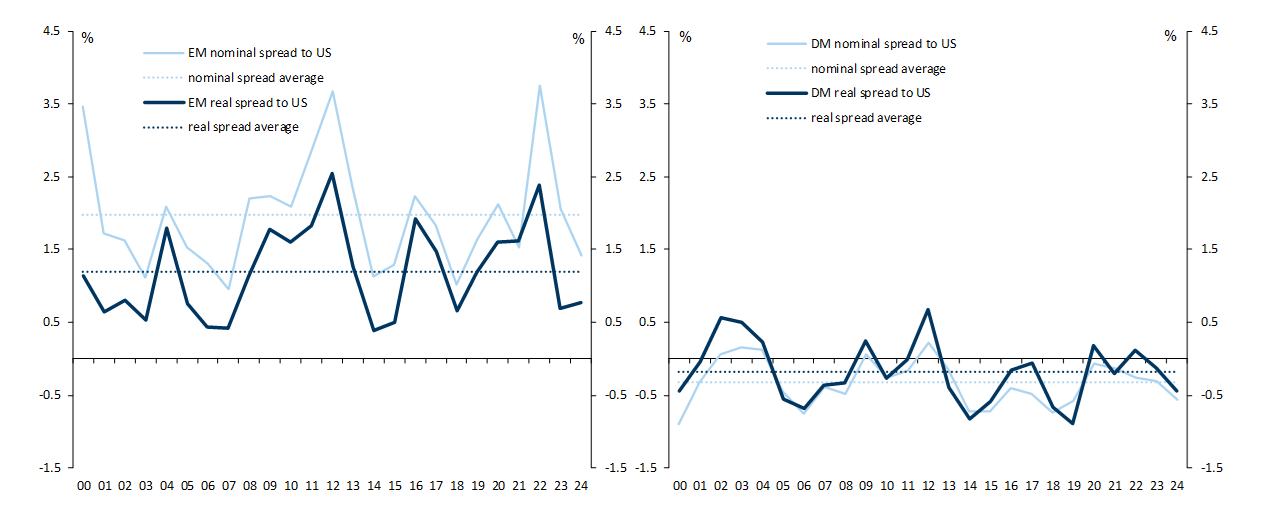

First, developments in EM and DM neutral real rates over the past 25 years have mostly been driven by changes in US/global r*, which have an almost one-for-one impact on other economies. Country-specific spreads have remained largely stable in aggregate, falling in some economies but rising in others.

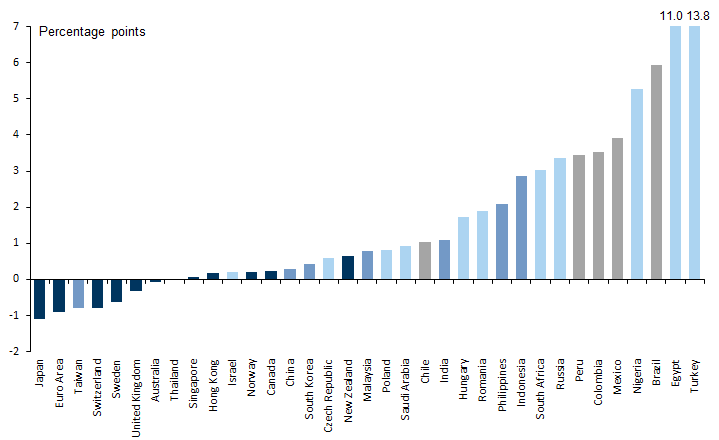

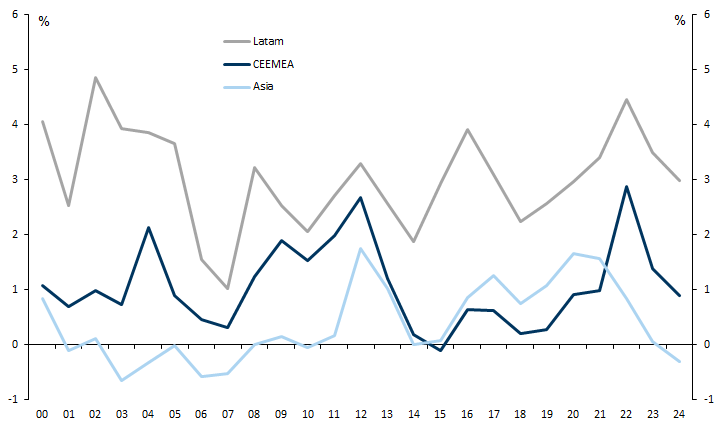

Second, in the latest five-year period (2020-24), the neutral real rate spread vs. the US has ranged from negative in some DM economies (notably Japan, the Euro area and Switzerland) to more than 10pp in some high-yield EM economies that have experienced major currency weakness (Turkey and Egypt).

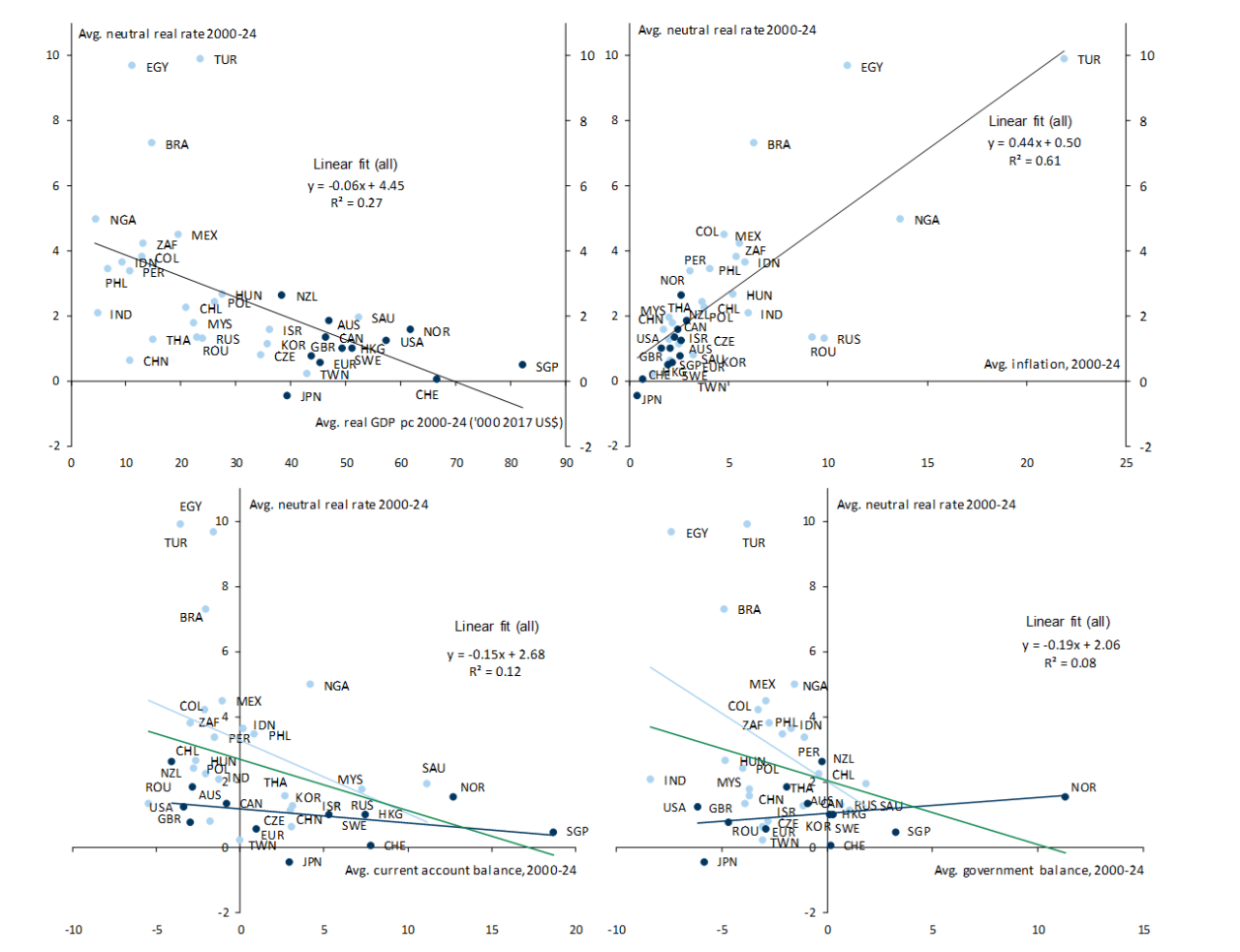

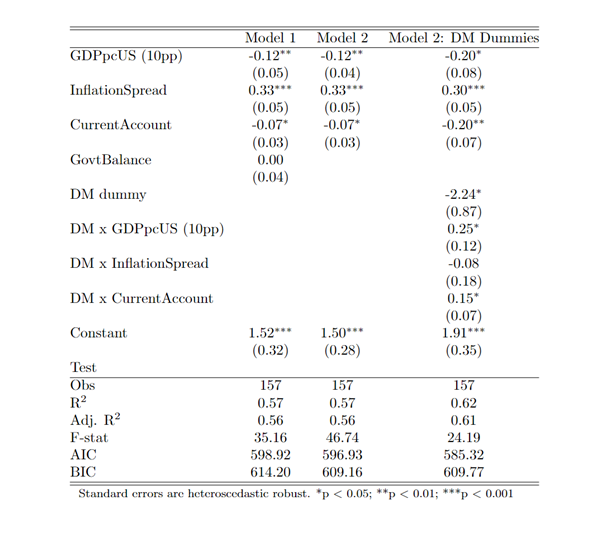

Third, we find that most of the cross-country variation in neutral real rates is accounted for by three factors: GDP per capita levels, inflation, and current account balances (the latter are a more important factor for EMs than DMs). A 10pp convergence in GDP per capita lowers neutral real rates (r*) by 12bp (all else equal), 1pp higher average inflation raises r* by 33bp, and a 1pp improvement in the current account balance lowers r* by 7bp (and by 20bp in EM economies). We find no independent role for a range of other factors, including GDP growth, government balances, and government debt levels.

Our results suggest that the returns from macroeconomic stabilisation are high. Economic convergence, lower inflation, and improved external balances provide a clear route to sustainably lower interest rates.

What Determines Cross-Country Differences in r*?

Estimating r*

Moving in Tandem with Global/US r*

Exhibit 1: Market Estimates of Neutral Nominal Rates in EM and DM Have Moved (Largely) in Tandem, Falling to a Trough in 2020 Before Rising Again

Exhibit 2: EM and DM Neutral Real Rates Have Also Moved in Tandem, With Long-Term Inflation Expectations Broadly Stable

Exhibit 3: The Spread vs. US for Both EM and DM Neutral Rates Fluctuates from Year to Year, But Around a Mean that Has Remained Stable

Accounting for Cross-Country Differences in r*

Exhibit 5: Neutral Real Rates Are Lower in Rich Countries, Higher in High-Inflation Economies, And Lower with Healthy Current Account and Government Balances

High Returns to Macroeconomic Stabilisation

Appendix: EM Regional Breakdown

EM Regional Breakdown

Exhibit 7: Neutral Real Rates Are Higher in LatAm Than in CEEMEA, and Lowest in Asia

- 1 ^ See Rungcharoenkitkul and Winkler (2022).

- 2 ^ We have focused on 3Y1Y rates as our proxy for the market’s assessment of neutral rates because this is the most actively traded and liquid expression of the market’s view on short-term rates at a medium-term horizon. However, other forward-rate expressions produce similar results.

- 3 ^ For the time-series charts (Exhibits 1-3), we only include the countries for which we have the full 25-year sample.

- 4 ^ This finding fits closely with a previous study by Clemens Grafe and Sara Grut that focused on neutral interest rates in CEEMEA economies.

- 5 ^ For a discussion of the estimated effects of each of these factors on US r*, see “What Have We Learned About the Neutral Rate?”, US Economics Analyst, 5 June 2023.

- 6 ^ Government balances have a significant role in single-variable regressions but this significance disappears when they are included together with current account balances. We do not find this surprising: the current account balance is the sum of public and private balances, so the result implies that that whole-economy balance (i.e., the current account) is a more important determinant of neutral rates than the government balance on its own.

- 7 ^ This result is consistent with the findings of a previous study by Jan Hatzius, Nicholas Fawcett, and Jari Stehn, who found that the link between growth and equilibrium real rates in DM economies has been weak (“Depressed R* Narrative: On Shaky Ground”, Global Economics Analyst, 29 November 2016).

- 8 ^ A result that follows directly from the Euler equation.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.