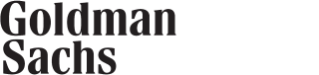

Several central banks—including the BoC, RBNZ, Riksbank, and the Fed—have started cutting sequentially, and we expect several others (including the ECB and BoE) to do so soon. In this comment we review the data dashboards that led central banks to pivot to sequential cuts so far and discuss the implications for central banks that have not.

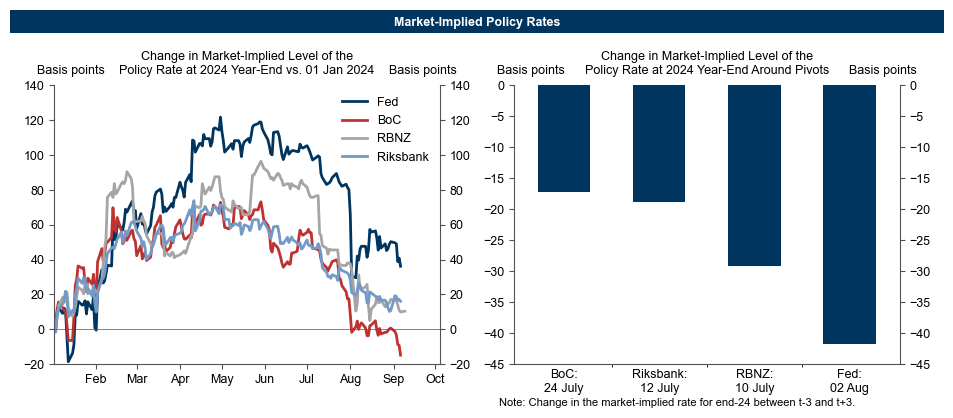

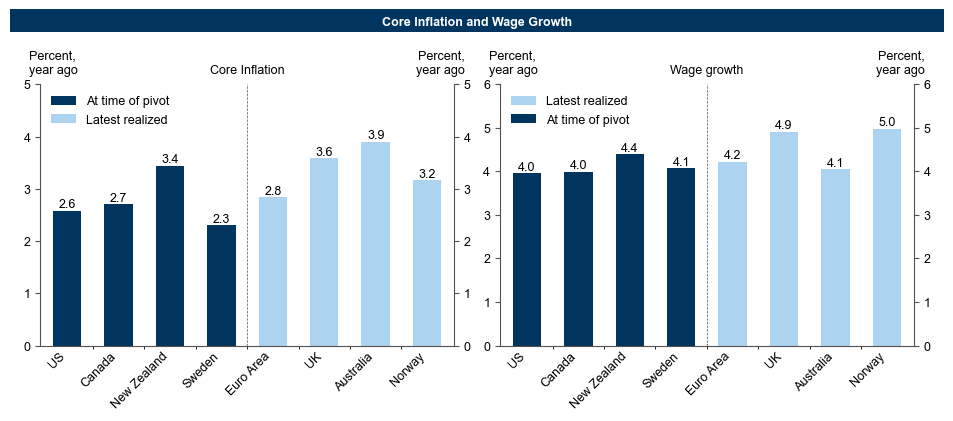

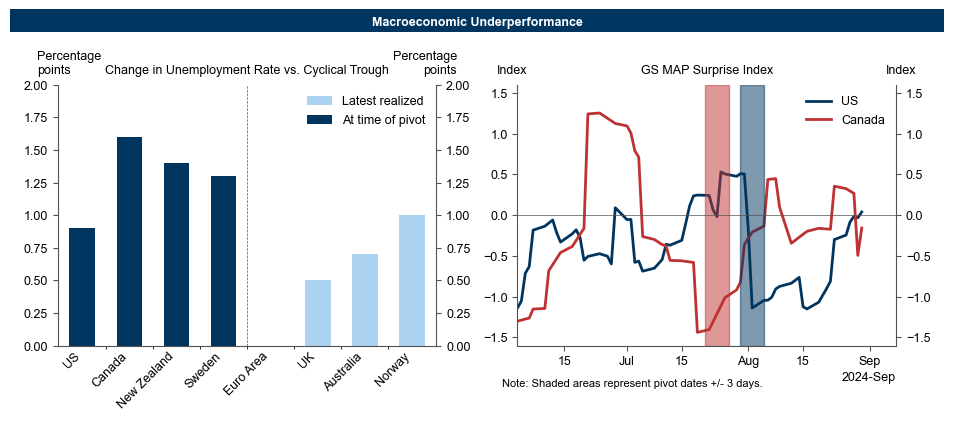

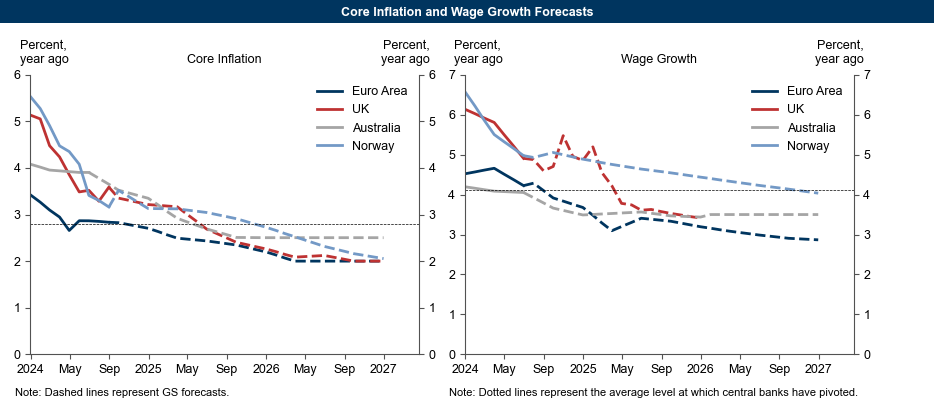

Data dashboards around pivots toward sequential cuts show three patterns. First, countries so far have only pivoted following substantial progress on core inflation and wage growth. Second, countries that have pivoted generally had larger policy rate overshoots relative to Taylor rule implied levels and higher real interest rates. Third, countries that have pivoted experienced a marked rise in unemployment and/or a downside growth surprise that raised concerns around the GDP outlook.

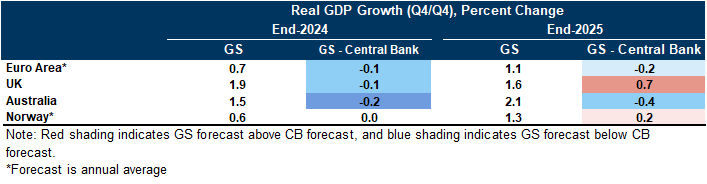

Under our forecasts, the Euro area will reach the average levels of core inflation and wage growth that permitted pivots in 2024Q4, followed by the UK and Australia in 2025H1. Moreover, our GDP forecasts are bearish relative to central bank expectations across all three economies. These patterns support our forecasts for a shift to sequential cuts for both the ECB (starting in December) and BoE (November). And while we continue to expect quarterly cuts in Australia and Norway, we expect that progress on inflation will keep the door open to an acceleration in rate cuts in the event of even moderate downside growth surprises.

What Prompts DM Pivots to Sequential Cuts?

Joseph Briggs

Megan Peters

- 1 ^ Since the RBNZ targets inflation of 1-3%, it may have a slightly greater tolerance for inflation above 3% than central banks that target inflation of 2% without an explicit range.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.