- Intro

- Forecasting long-term S&P 500 returns

- Investment implications

- Outlook for aggregate vs. equal-weight performance

- How our long-term equity return forecast compares with consensus

- Considerations for portfolio managers with long investment horizons

- Appendix A: Components of our long-term equity return model

- Appendix B: Risks to our forecast

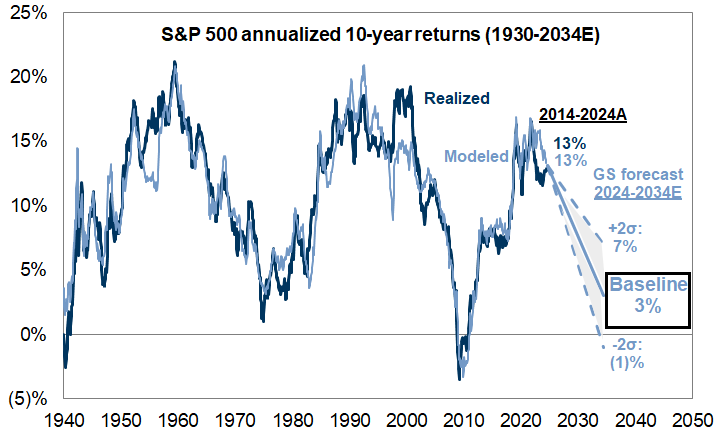

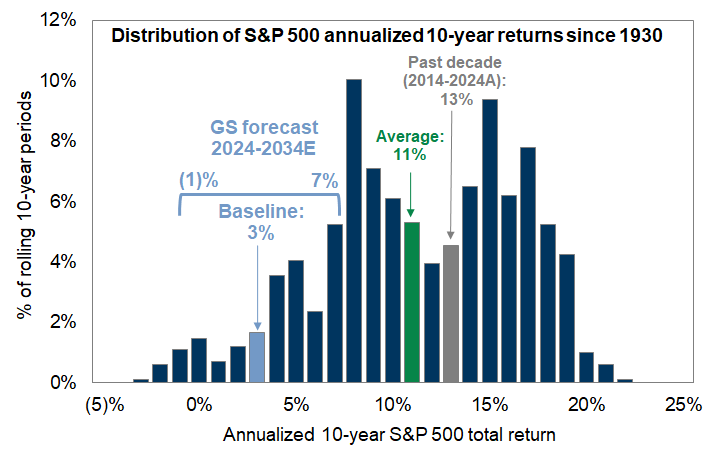

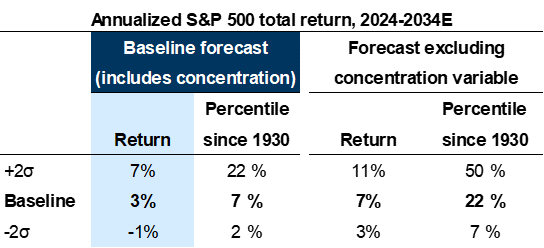

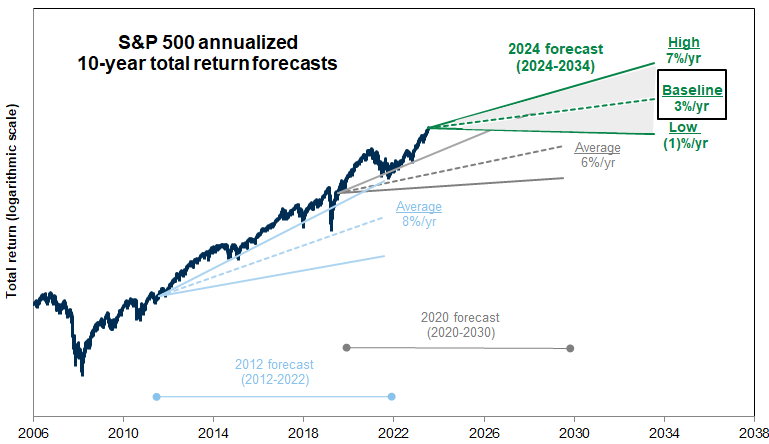

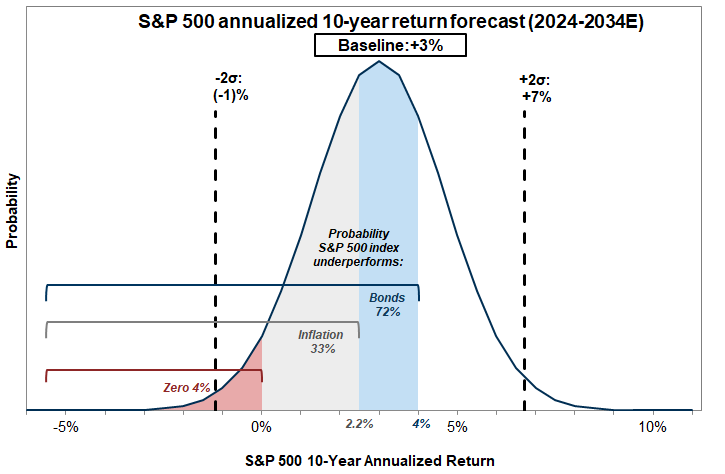

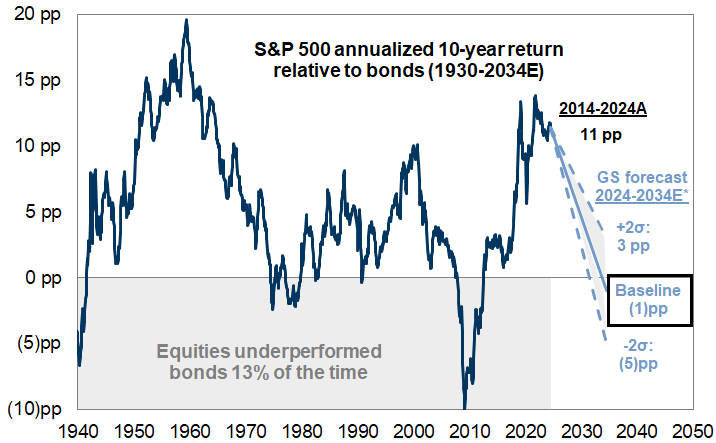

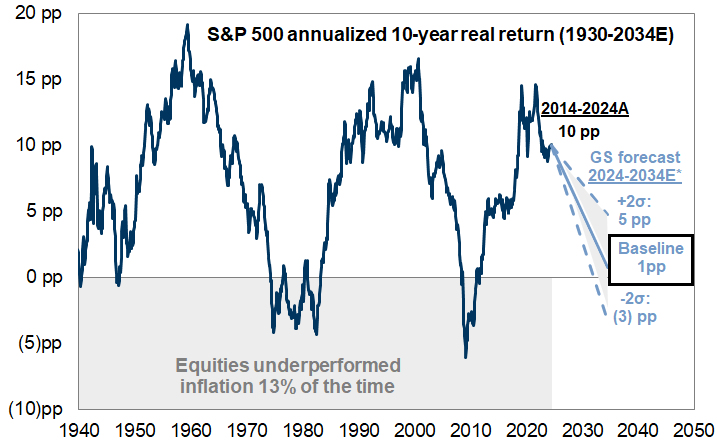

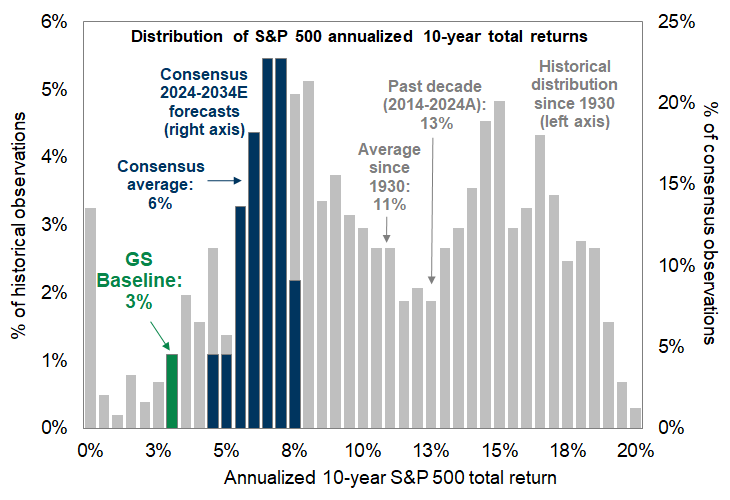

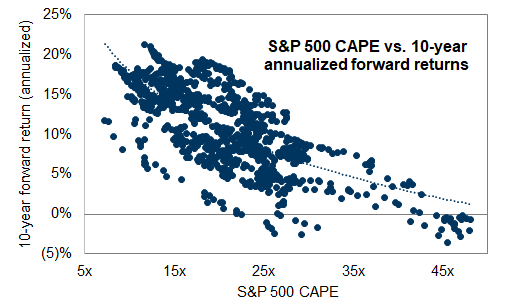

We estimate the S&P 500 will deliver an annualized nominal total return of 3% during the next 10 years (7th percentile since 1930) and roughly 1% on a real basis. Annualized nominal returns between -1% and +7% represents a range of likely outcomes around our baseline forecast and reflects the uncertainty inherent in forecasting the future. During the past decade the S&P 500 posted a 13% annualized total return (58th percentile).

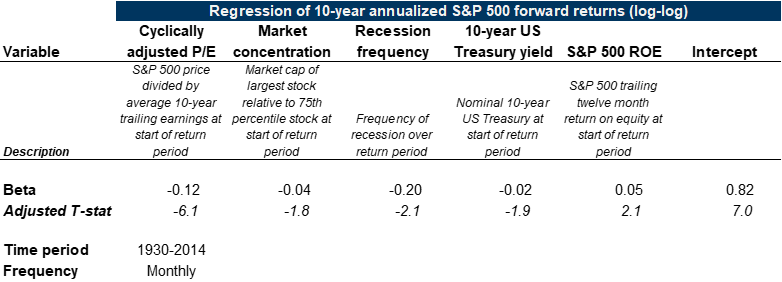

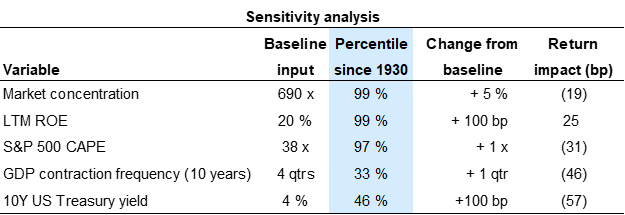

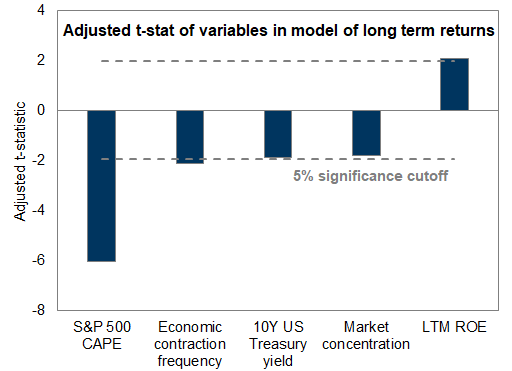

We model prospective long-term equity returns as a function of five variables: (1) starting absolute valuation, (2) stock market concentration, (3) economic contraction frequency, (4) corporate profitability, and (5) interest rates.

Our forecast would be 4 pp greater than our baseline if we exclude a variable for market concentration that currently ranks near the highest level in 100 years. The 7% return would rank in the 22nd historical percentile.

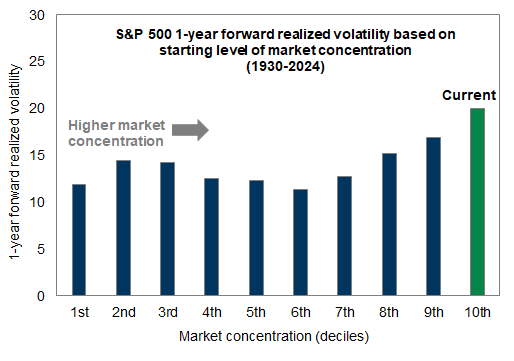

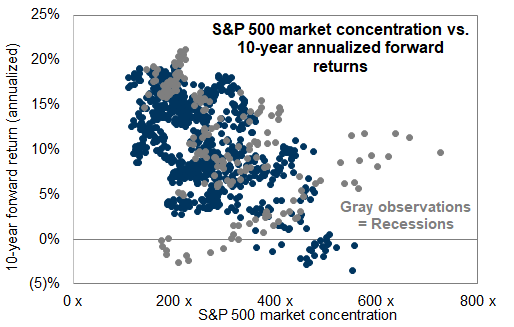

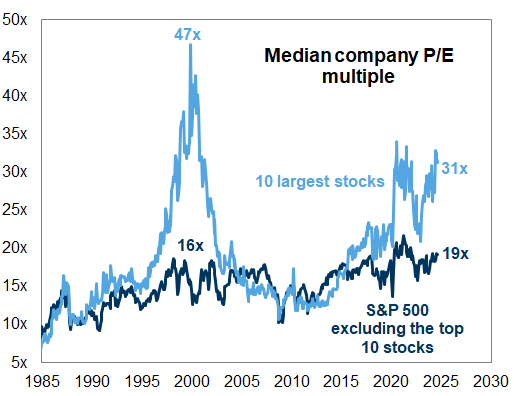

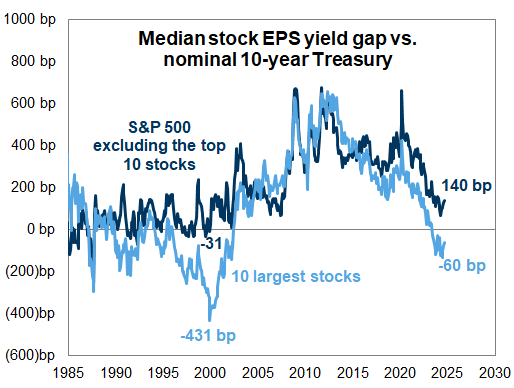

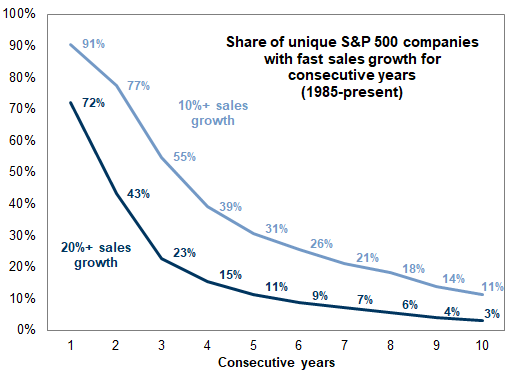

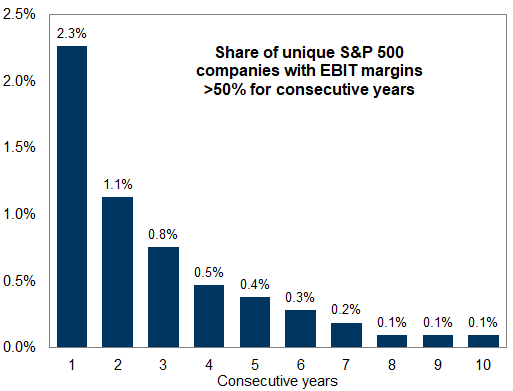

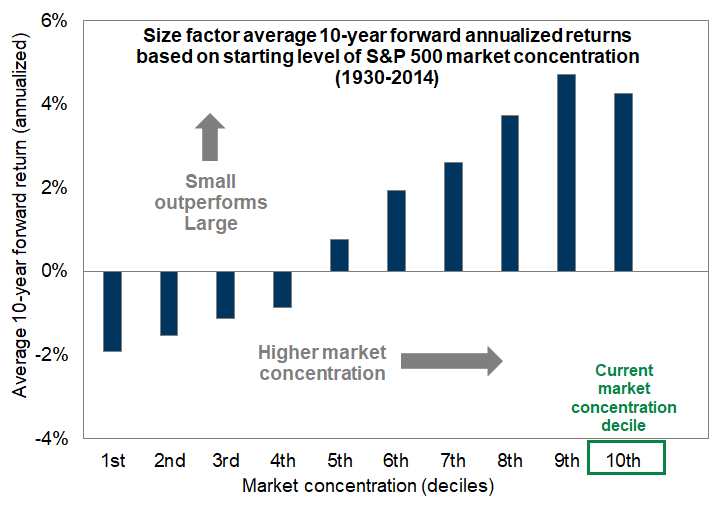

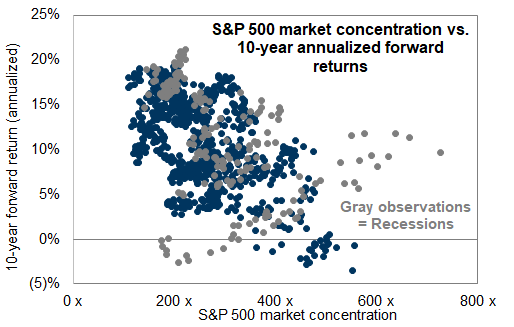

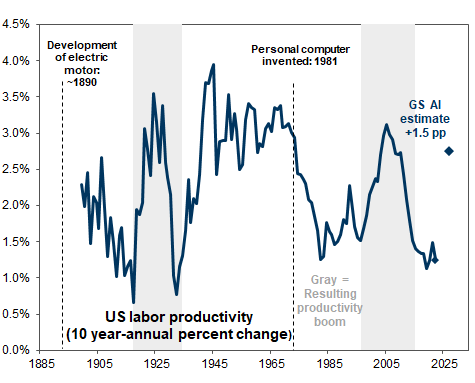

The intuition for why concentration matters for long-term returns relates to growth in addition to valuation. Our historical analyses show that it is extremely difficult for any firm to maintain high levels of sales growth and profit margins over sustained periods of time. The same issue plagues a highly concentrated index. Furthermore, the risk embedded in high concentration markets is not always reflected in valuation.

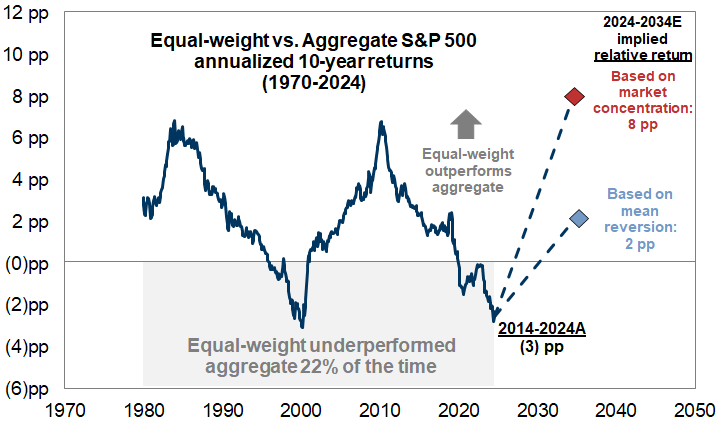

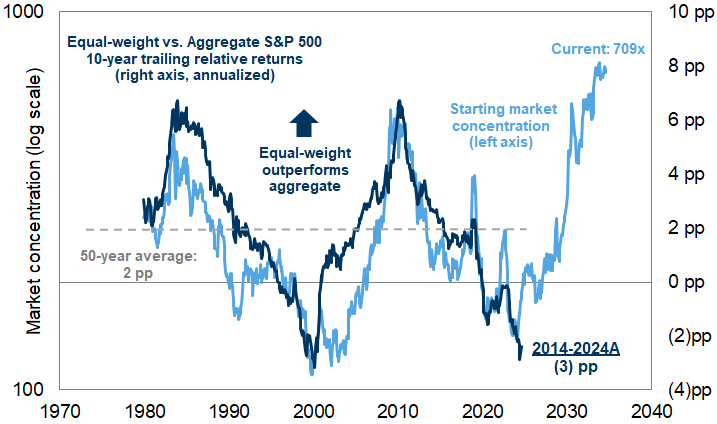

We expect the return structure of the stock market will broaden in the future. Today's extremely high market concentration suggests that the S&P 500 equal-weight benchmark (SPW) is likely to outperform the cap-weighted aggregate index (SPX) during the next decade by an annualized 200 bp-800 bp.

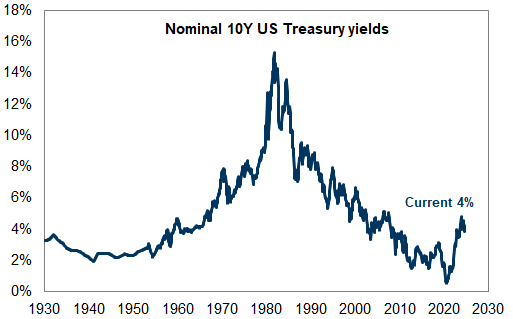

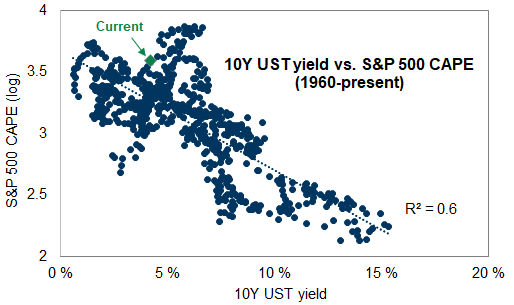

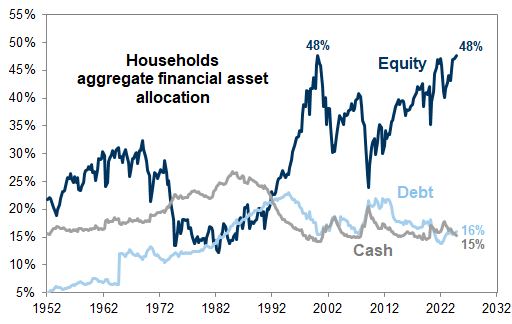

Our forecast suggests equities will face stiff competition from other assets during the next decade. Our 3% annualized equity return forecast combined with a current ten-year US Treasury yield of 4% and ten-year breakeven inflation of 2.2% suggests the S&P 500 has roughly a 72% probability of trailing bonds and a 33% likelihood of lagging inflation through 2034. Excluding concentration, the probabilities of underperforming would be 7% and 1%, respectively.

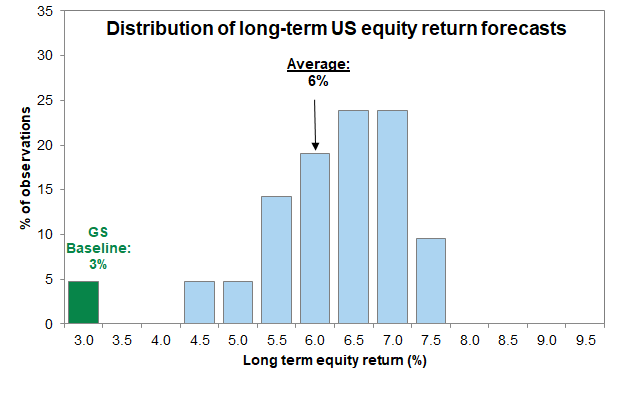

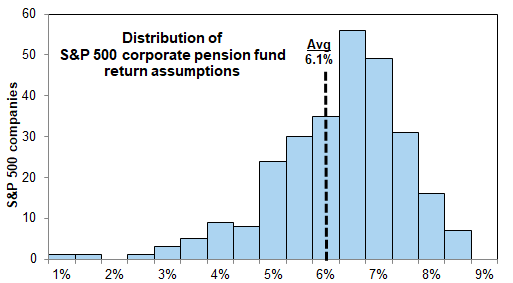

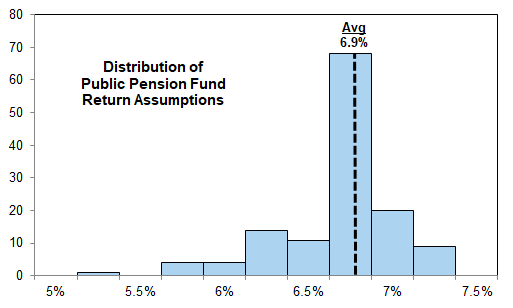

Our S&P 500 baseline 10-year return forecast is lower than the estimates of other market participants. Buy- and sell-side projections of the long-term return of US stocks averages 6% (range of 4% to 7%).

Forecasting long-term S&P 500 returns

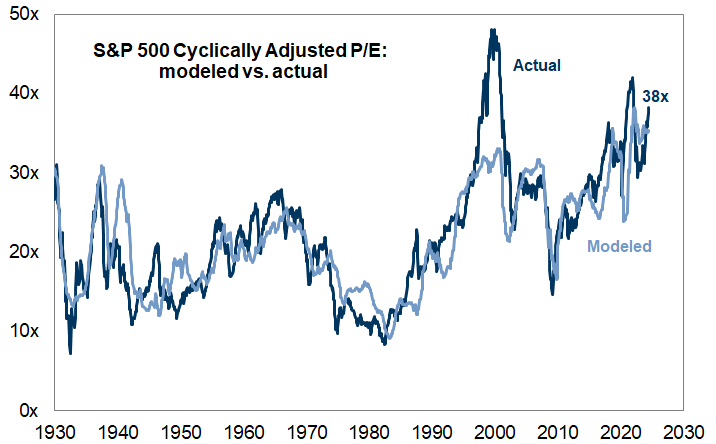

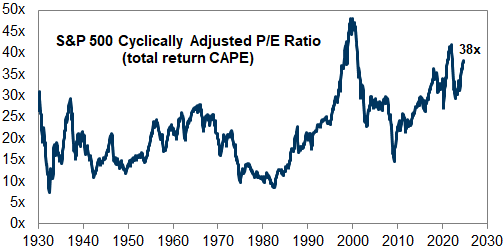

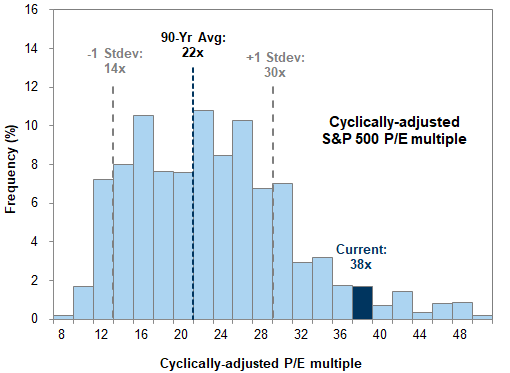

Valuation: S&P 500 cyclically adjusted P/E multiple (CAPE)

Economic fundamentals: Economic contraction frequency

Interest rates: 10-year US Treasury yield

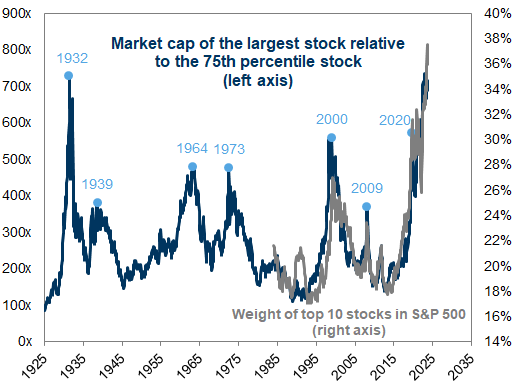

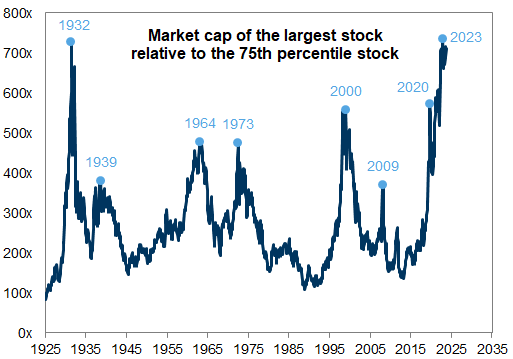

Market concentration: Ratio of the market cap of the largest-cap stock vs. the 75th percentile stock

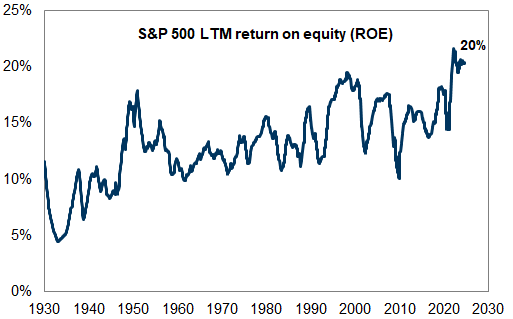

Profitability: LTM S&P 500 return on equity (ROE)

Exhibit 4: Sensitivity analysis around our baseline long-term US equity return forecast

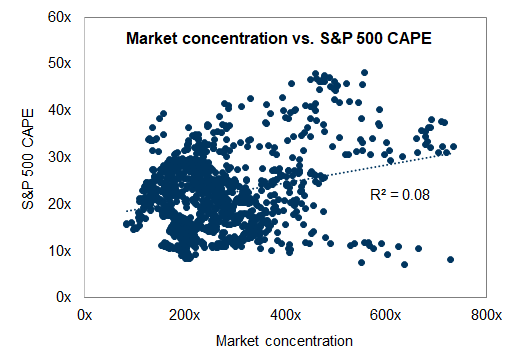

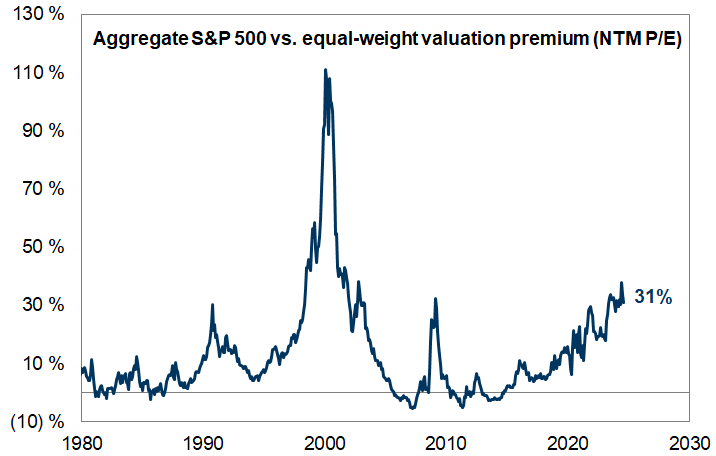

Valuation

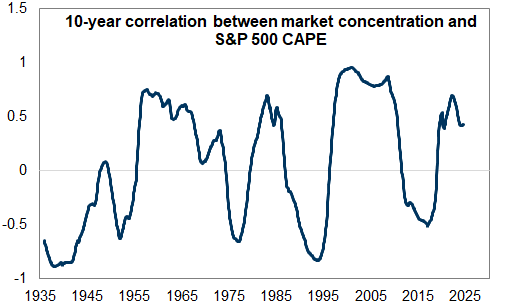

Market Concentration

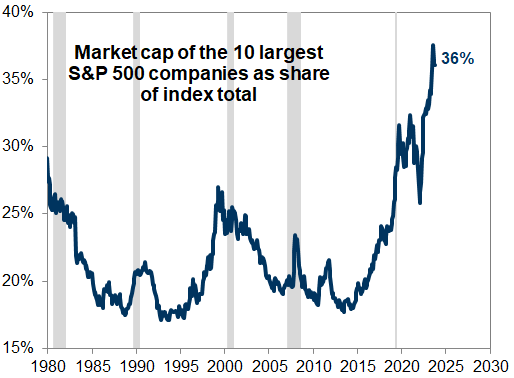

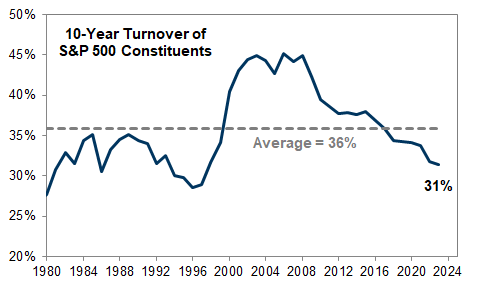

Exhibit 7: The 10 largest stocks in the S&P 500 account for more than a third of total market cap

Exhibit 8: US equity market concentration 1925-2024

Exhibit 11: Higher starting market concentration associated with higher volatility

Exhibit 12: Outside of recessions higher market concentration is associated with lower forward returns

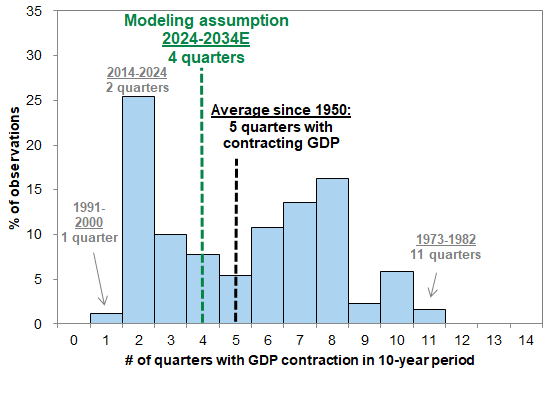

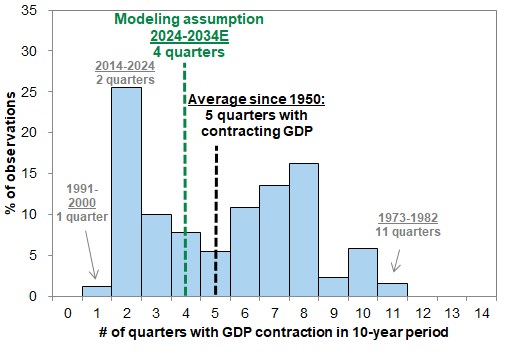

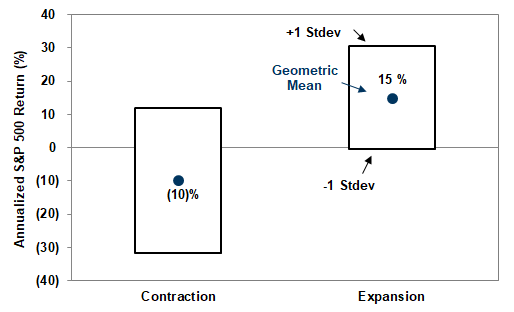

Economic contraction frequency

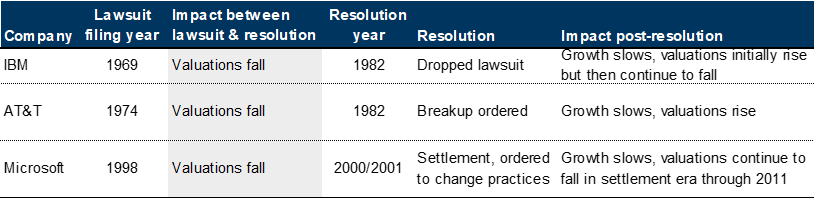

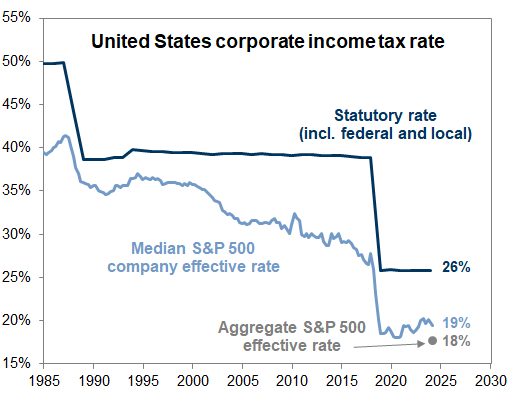

Risks to our forecast

Investment implications

Exhibit 22: Relative performance of equities and inflation

Outlook for aggregate vs. equal-weight performance

Exhibit 24: Higher market concentration implies future outperformance of low market cap vs. high market cap stocks

How our long-term equity return forecast compares with consensus

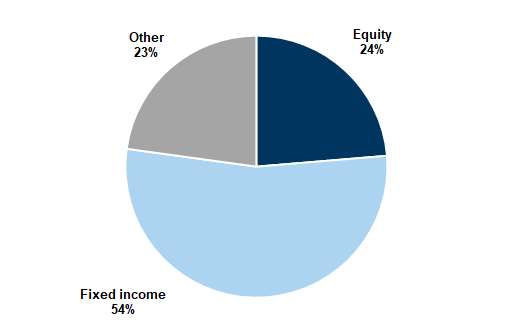

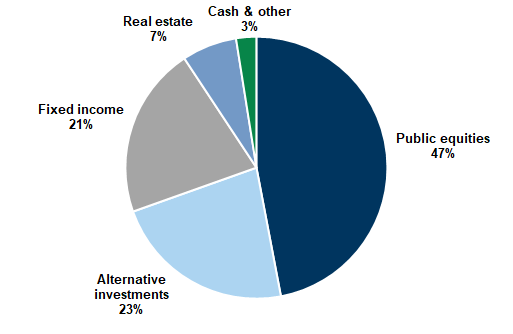

Considerations for portfolio managers with long investment horizons

Appendix A: Components of our long-term equity return model

Components of our long-term return forecast model

Valuation: S&P 500 cyclically adjusted P/E multiple (CAPE)

Economic fundamentals: Economic contraction frequency

Interest rates: 10 year US Treasury yield

Market concentration: Ratio of the market cap of the largest-cap stock vs. the 75th percentile stock

Profitability: LTM S&P 500 return on equity (ROE)

Valuation

Economic contraction frequency

Interest Rates

Market Concentration

Exhibit 41: Market concentration over time

Profitability

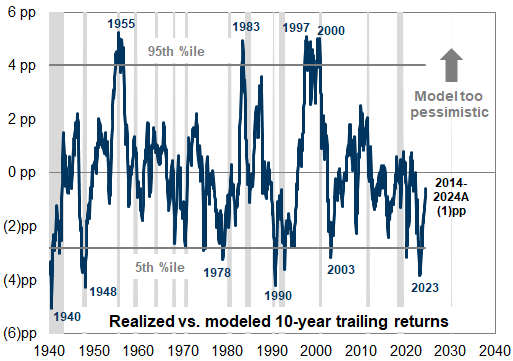

Historical periods where our model fails to explain returns

Appendix B: Risks to our forecast

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.