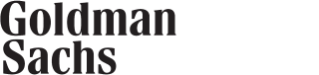

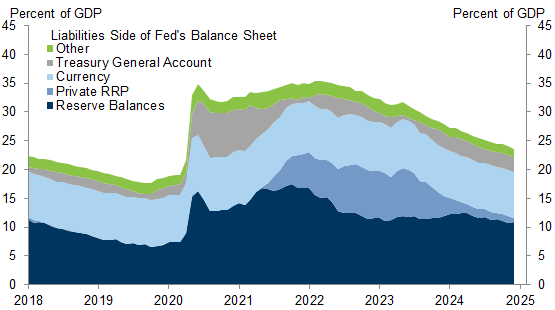

Last May, the Fed cut the pace of quantitative tightening (QT) in half in order to shrink the balance sheet more cautiously and facilitate the redistribution of reserves across banks. Since then, the Fed’s balance sheet has shrunk by another $400bn to $7tn, which has been largely absorbed by a $330bn decline in the reverse repo (RRP) facility.

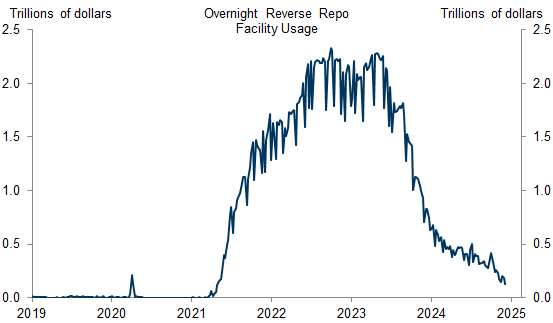

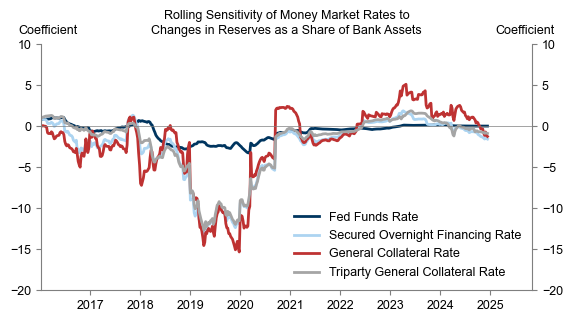

Key indicators of money market conditions suggest that bank reserves remain “abundant.” However, noticeable increases in money market rates at the end of September and a modestly higher sensitivity to changes in reserves in some pockets of funding markets over the last couple of months suggest that runoff is slowly bringing reserve levels towards the “ample” region that the FOMC is aiming for.

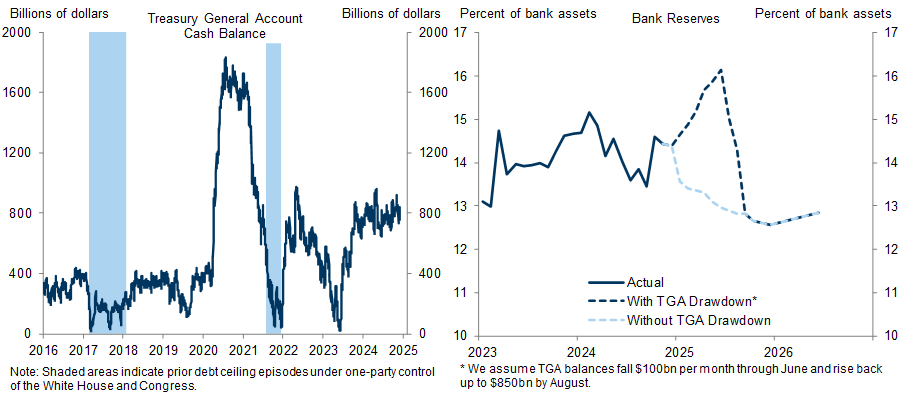

Fed officials appear to be in no rush to end QT given that reserves are still abundant. However, the combination of ongoing balance sheet runoff with the reinstatement of the debt limit—which will keep reserve balances temporarily elevated by squeezing the Treasury General Account (TGA)— will likely make it hard for the FOMC to gauge when to stop QT in the first half of next year.

To give the Committee more time to evaluate conditions in money markets and avoid rate spikes when TGA balances start rising again, we expect the FOMC to slow the pace of runoff further at the January meeting. The most likely implementation is for the FOMC to stop runoff of Treasury securities and keep the current $35bn cap on mortgage-backed securities (MBS) unchanged, consistent with the Committee’s goal of tilting the balance sheet towards Treasuries over time. This would likely slow the realized monthly pace of runoff to around $20bn going forward (vs. $40-45bn currently).

Given the slower pace of runoff, we now expect QT to stop at the end of 2025Q2 (vs. 2025Q1 previously), when reserves are around 13% of bank assets and the balance sheet is around 22% of GDP. We continue to expect the Fed’s remaining balance sheet runoff to have modest effects on interest rates, financial conditions, growth, and inflation. We also expect these changes to have minimal effects on net Treasury supply, as two fewer months of runoff than our prior forecast (worth $50bn) are offset by a later start of MBS reinvestments into Treasuries (worth $50-60bn), which we expect to begin once QT ends.

The Fed’s Balance Sheet Runoff: Tapering to Avoid a Tantrum

Manuel Abecasis

William Marshall

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.