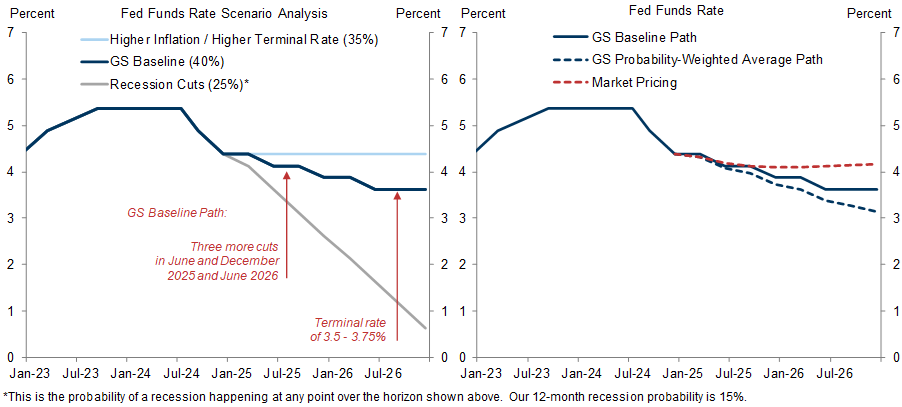

We pushed back the final three rate cuts in our Fed forecast on Friday morning in response to the strong December employment report, which alleviated some of the lingering concerns about recent labor market softening. We now expect two cuts this year in June and December and one more in 2026 (vs. three this year previously) to an unchanged terminal rate of 3.5-3.75%.

Our baseline forecast remains somewhat more dovish than market pricing mainly because we are more optimistic than many that the underlying inflation trend will continue to fall toward 2%. But it is hard to have great conviction in the timing of cuts because the economic data we expect—a healthy labor market and lower inflation—would make cuts reasonable but not critical, and because it is hard to know how the FOMC will navigate likely tariff increases.

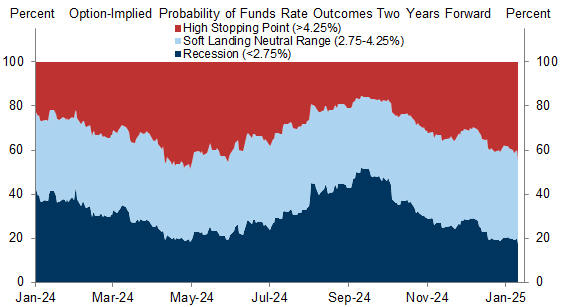

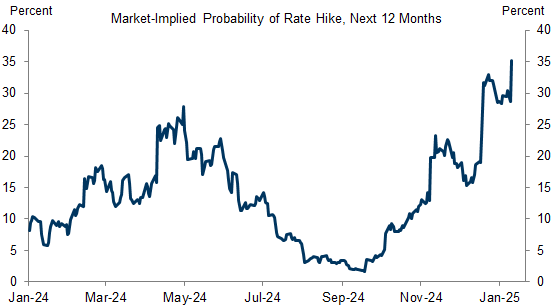

We have more conviction that market pricing as a statement about the probability-weighted path of the funds rate over the next few years across many possible scenarios is too hawkish, and in particular that the market-implied probability of rate hikes is too high. This reflects both our inflation optimism and our view that the implications of the new administration’s policies for interest rates are not as strongly and unambiguously hawkish as widely assumed. We do not expect fiscal or immigration policy changes to boost inflation appreciably, and we find it hard to envision tariffs that raise inflation enough to make a plausible case for hiking that do not also unsettle the equity market, as even much smaller tariffs did in 2019.

Our Fed Views vs. Market Pricing After the Employment Report

David Mericle

Will Marshall

Bill Zu

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.