Most equities have entered, or are on the cusp of, a bear market.

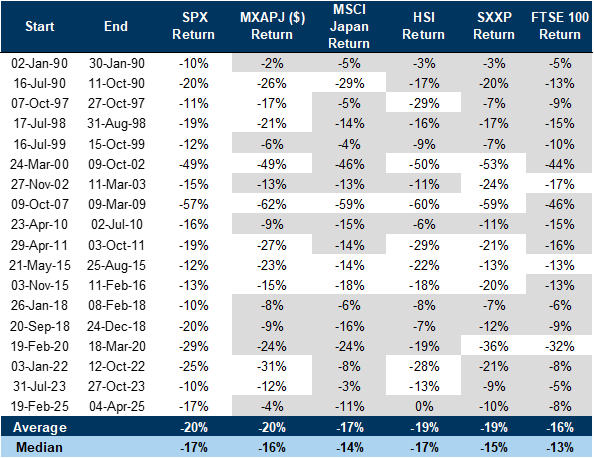

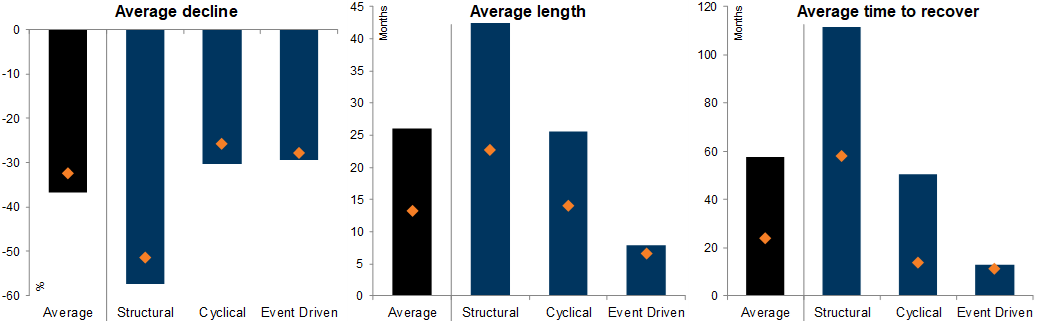

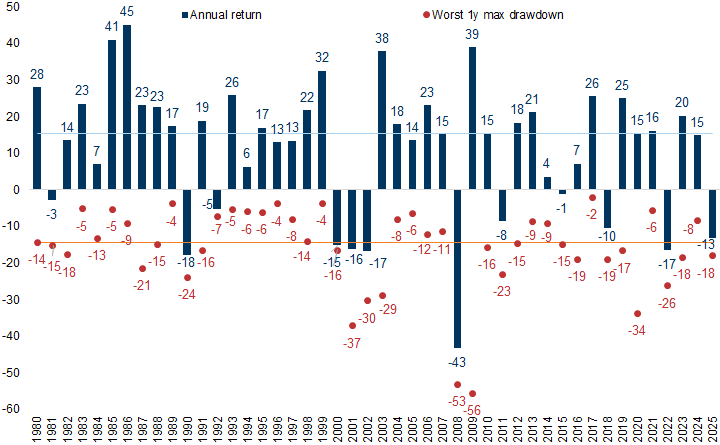

Not all bear markets are the same. The type of bear market has some bearing on the triggers, timing and speed of the recovery.

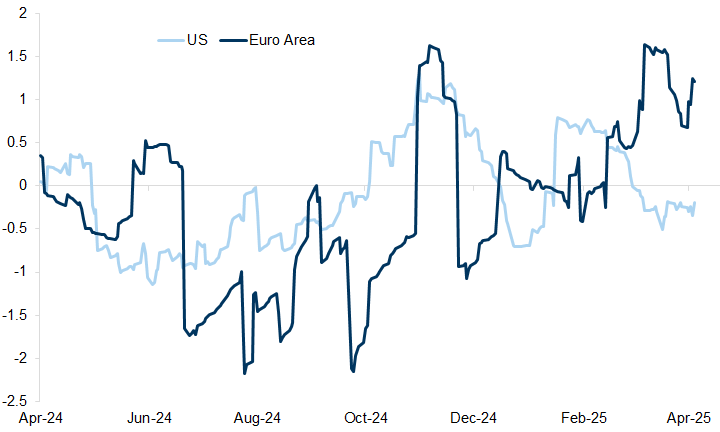

Our framework identifies 3 types: 'Structural' bear markets – triggered by structural imbalances and financial bubbles; 'Cyclical' bear markets – typically triggered by rising interest rates, impending recessions and falls in profits; 'Event-driven' bear markets – triggered by a one-off 'shock' that either does not lead to a domestic recession or temporarily knocks a cycle off course. Cyclical bear markets are the most common, with falls averaging 30%.

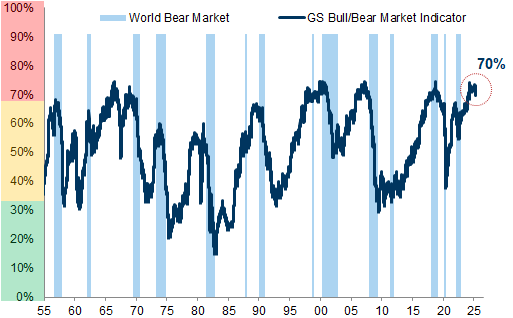

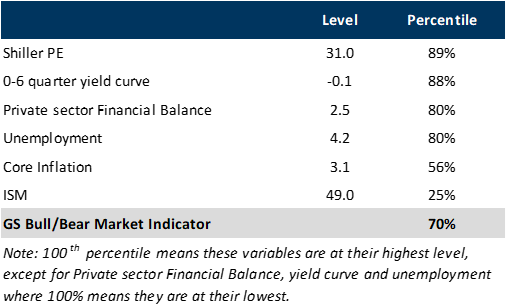

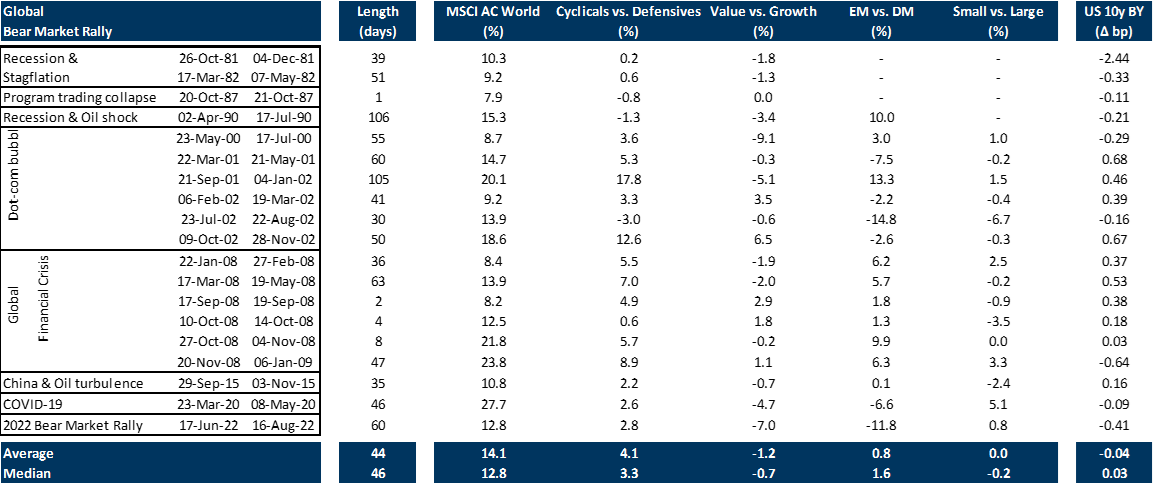

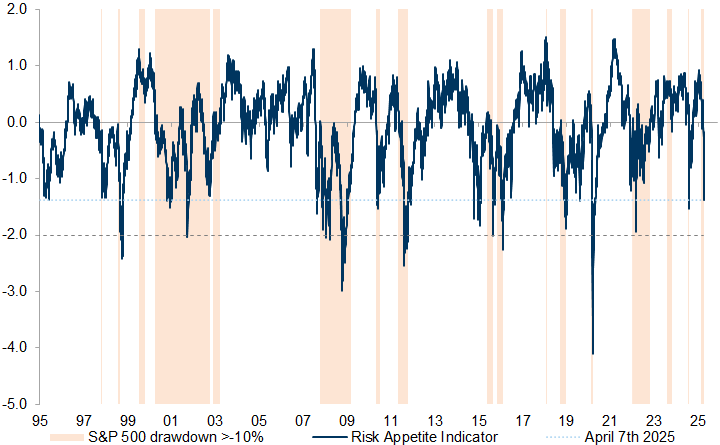

Bear market rallies are common, but a sustained trough typically requires a combination of cheap valuations, extreme negative positioning, policy intervention and a slowing of macro deterioration. Our Bull/Bear indicator (GSBLBR) remains elevated.

We would argue that we are in an event-driven bear market (triggered by tariffs). However, it could easily morph into a cyclical bear market given growing recession risk. The average falls of around 30% are similar for both event-driven and cyclical bear markets, while they differ in terms of duration with event-driven downturns being shorter with a faster recovery profile.

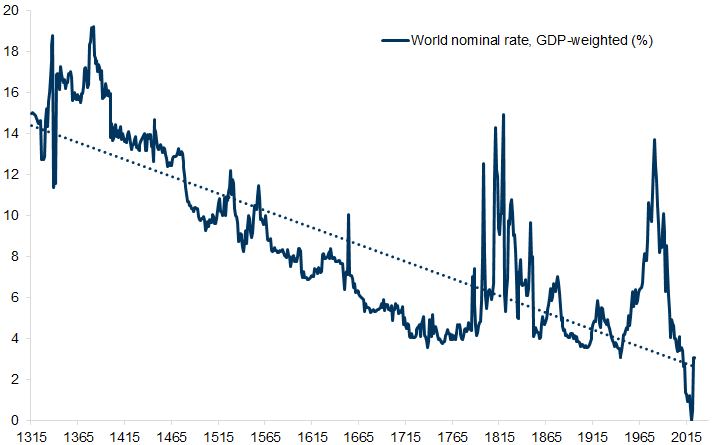

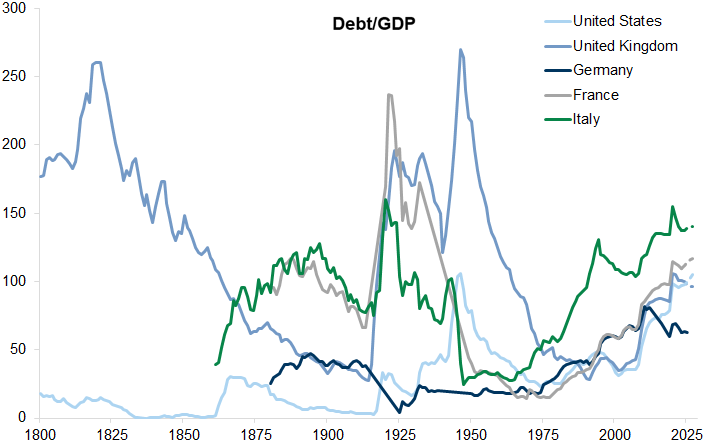

Over the medium term, secular inflection points in the 'Post Modern Cycle', including less globalisation, higher budget deficits, higher cost of capital and constraints on corporate profit margins, are likely to weigh on returns on investment, increasing the case for diversification.

Bear Market Anatomy - the path and shape of the bear market

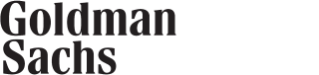

Exhibit 1: Recent shifts in policy are reflected in macro surprises

How far and how deep?

Structural bear markets – triggered by structural imbalances and financial bubbles. Very often there is a 'price' shock such as deflation and a banking crisis that follows.

Cyclical bear markets – typically triggered by rising interest rates, impending recessions and falls in profits. They are a function of the economic cycle.

Event-driven bear markets – triggered by a one-off 'shock' that either does not lead to a domestic recession or temporarily knocks a cycle off course. Common triggers are wars, an oil price shock, an EM crisis or technical market dislocations. The principal driver of an event-driven bear market is higher risk premia rather than a rise in interest rates at the outset.

Exhibit 5: GS Bull/Bear Market Indicator (GSBLBR)

Exhibit 6: Details of components of the GS Bull/Bear Market Indicator

The Bear Market Bounce

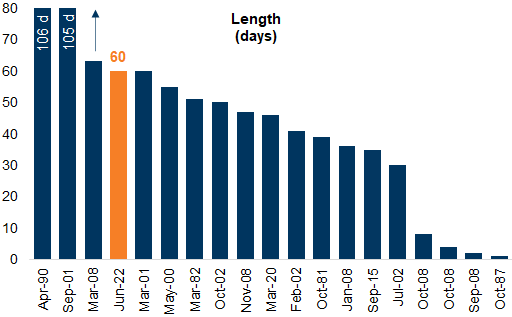

Exhibit 8: Duration of bear market rallies

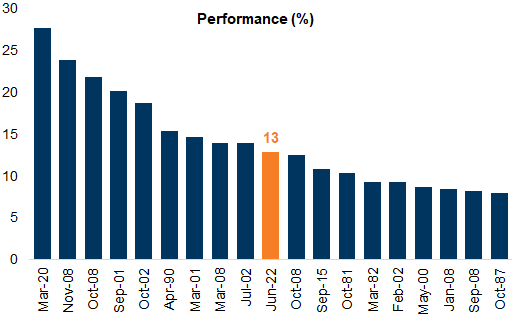

Exhibit 9: Performance of bear market rallies

Conditions for a recovery

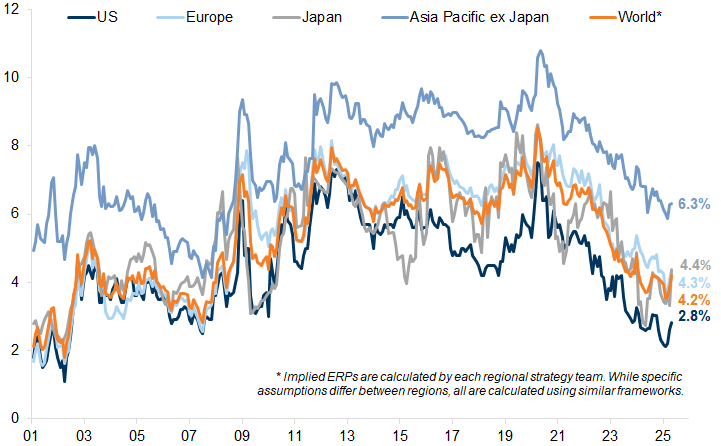

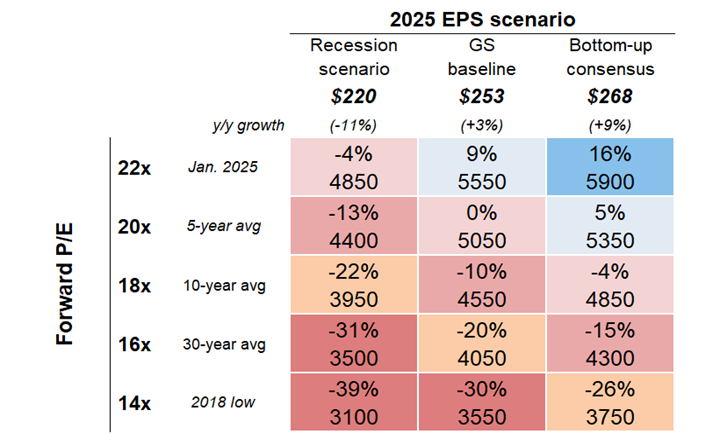

Attractive valuations

Extreme positioning

Policy support

A sense that the second derivative of growth is improving

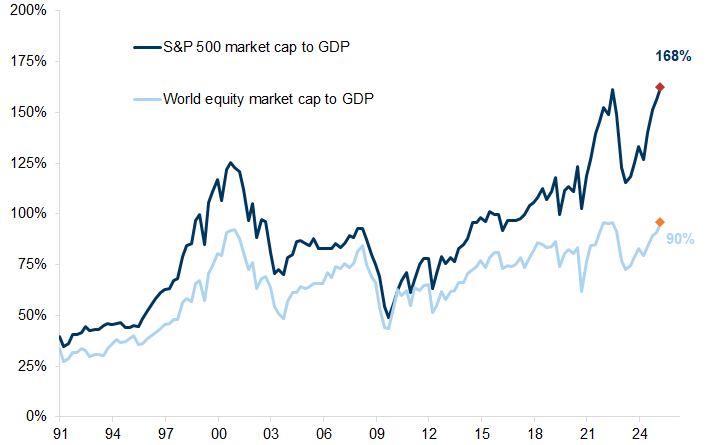

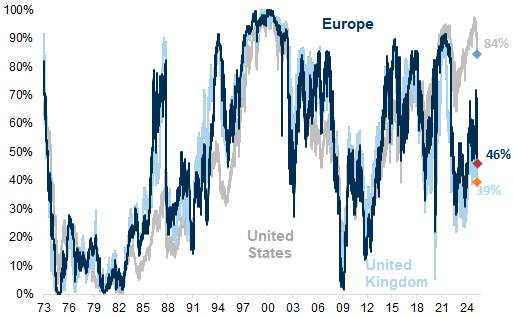

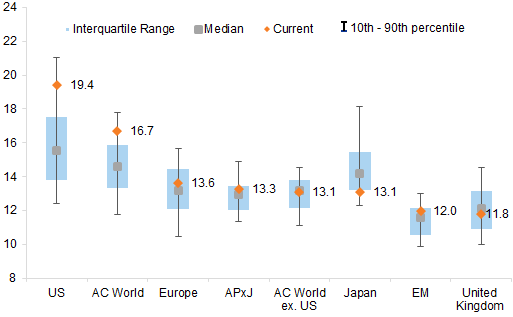

Valuations remain expensive

Exhibit 12: Valuations are neither expensive (as in the US) nor cheap

Exhibit 13: Non-US markets, while cheap relative to the US, are not particularly inexpensive relative to their own history

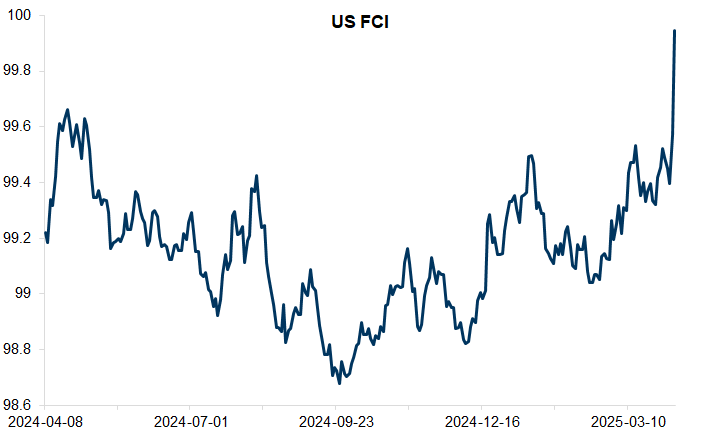

Interest rates

Cyclical bear markets around 'soft landings' are likely to end around a move lower in interest rates.

Cyclical bear markets associated with 'hard landings' are not likely to be resolved by interest rates alone. Interest rate cuts are an important part of the recovery puzzle, but a slowing in the second derivative of growth, together with depressed valuations, also tends to be important.

Growth momentum

Positioning

Structural changes and the post-modern cycle

Long-term fall in interest rates and the cost of capital

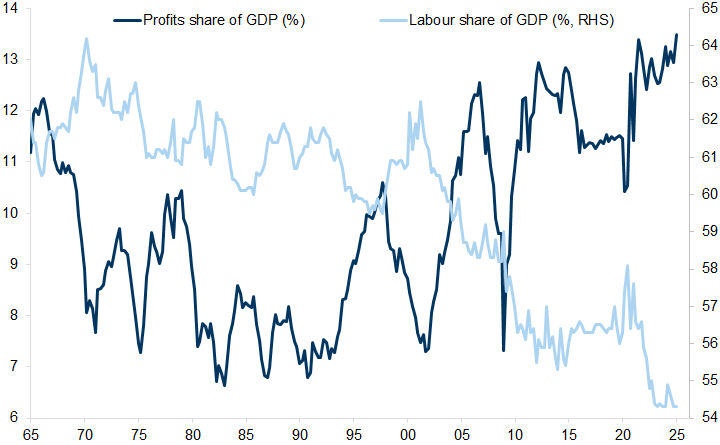

Long-term rise in margins and profit shares of GDP

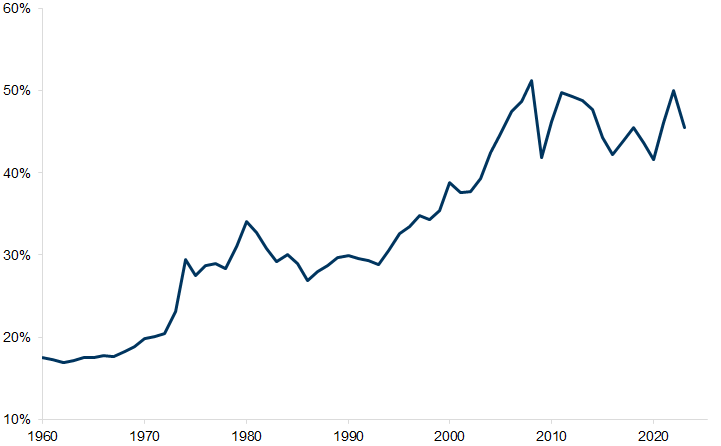

Secular rise in world trade growth

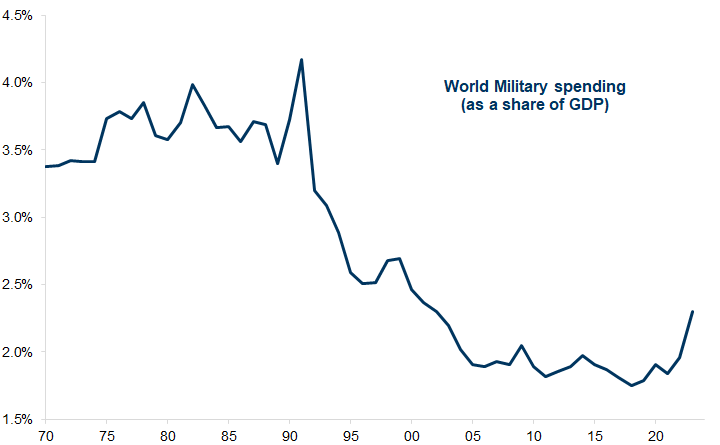

Structural decline in government spending on defense

Long-term interest rates

World trade growth

Margins and profit shares of GDP

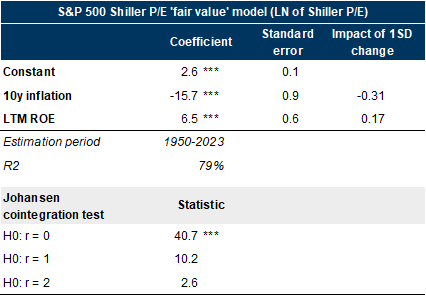

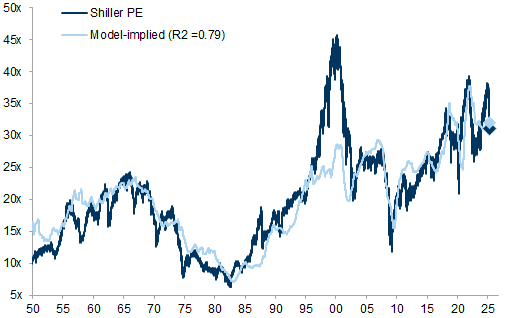

Exhibit 23: A simple model combining inflation and ROE has explained a large part of the variation in US equity valuations since WW2

Exhibit 24: Trends in inflation and corporate profitability have had the largest impact on S&P 500 valuations

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.