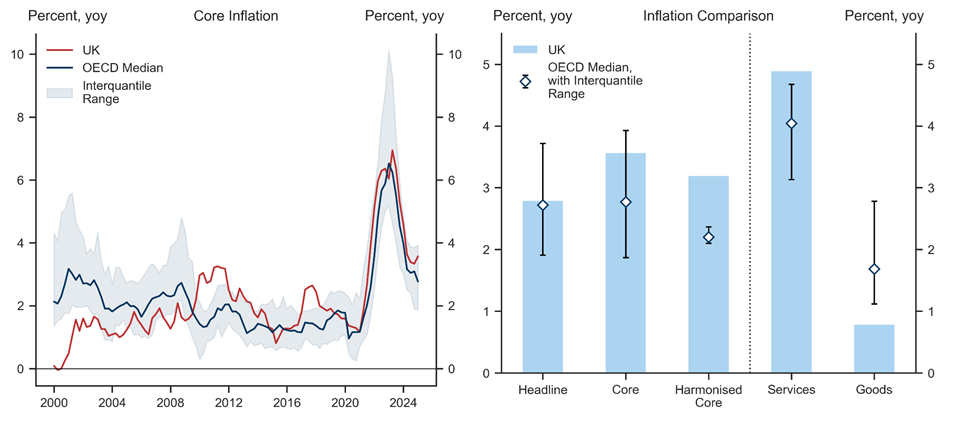

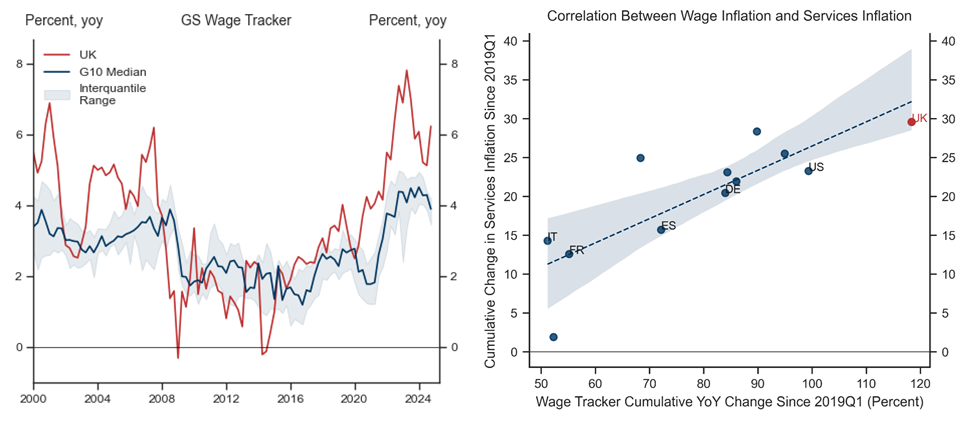

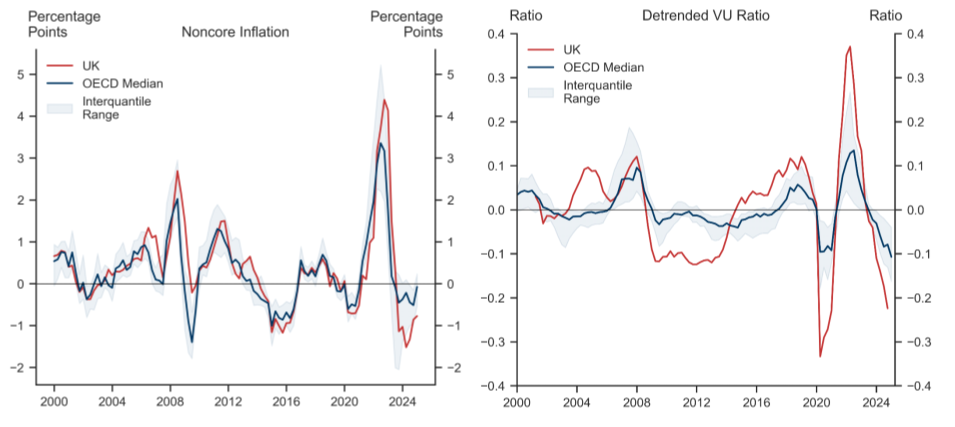

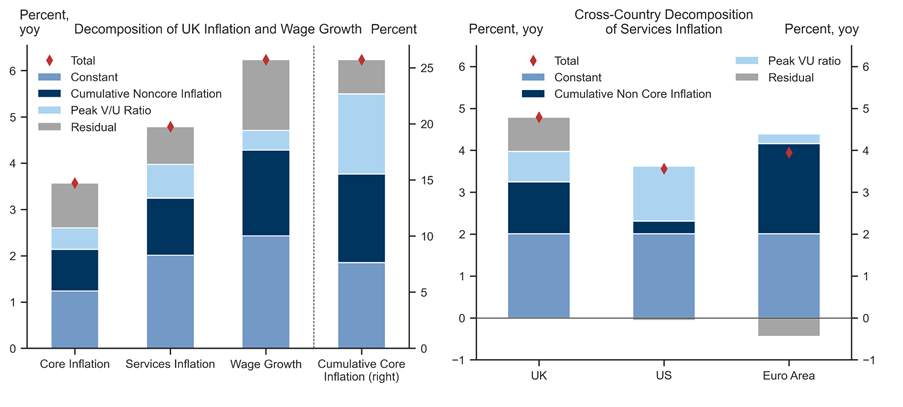

UK core inflation continues to run notably ahead of that in other countries, reflecting high services inflation and firm wage growth. Compared with other OECD countries, the UK saw a much bigger increase in food and energy prices after Covid, with more labour market overheating (measured by the peak vacancy/unemployment ratio).

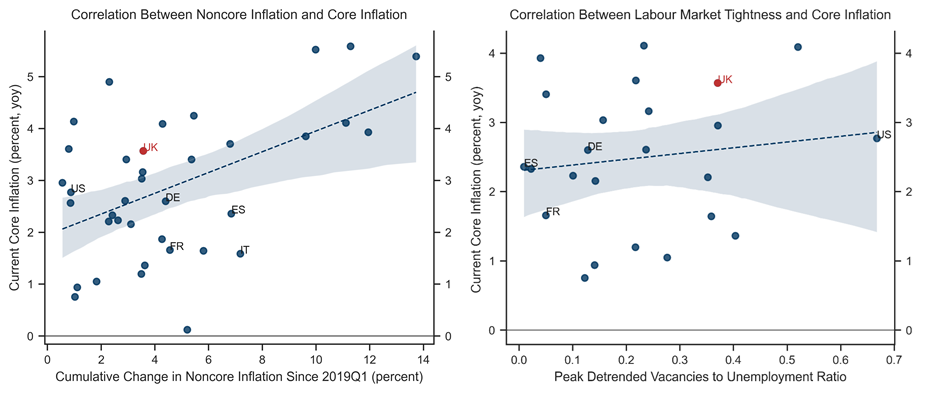

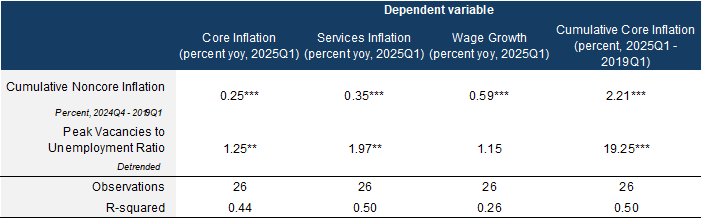

Simple cross-country regressions suggest that pass-through from the sharp post-Covid rise in noncore prices and labour market overheating play an important role in explaining why UK core inflation, services inflation and wage growth pressures remain elevated compared with other advanced economies.

Given the recent drop in noncore prices and the vacancy/unemployment (V/U) ratio—which has been more pronounced in the UK than elsewhere—our analysis suggests that UK inflationary pressures should cool notably in coming quarters. We therefore ultimately expect UK inflation to look similar to that in other advanced economies, allowing the BoE to lower rates more than priced.

Why is Inflation Still So High? A Cross-Country Perspective

Exhibit 1: UK Inflation Remains Notably Higher than Elsewhere, Reflecting High Services Inflation

Not That Different After All?

- 1 ^ We de-trend the V/U ratio to allow for structural changes.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.