The Fed’s monetary policy framework review is underway. The FOMC will release its revised “Statement of Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy” (or “consensus statement”) later this summer and will announce any changes it makes to its communications practices this fall.

The last framework review in 2020 was heavily influenced by a long period of low inflation and concern that a very low neutral rate would make the zero lower bound (ZLB) a more frequent problem in the future. Two of the key ideas that came out of it were that monetary policy should respond to “shortfalls” from maximum employment but not to labor market tightness unaccompanied by signs of inflationary pressure, and “flexible average inflation targeting” (FAIT), under which the FOMC would allow inflation to modestly overshoot 2% after prolonged periods of low inflation in order to average 2% over time and keep inflation expectations anchored.

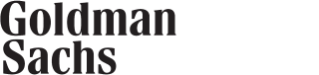

Some critics have argued that these ideas contributed to high inflation during the pandemic by delaying the Fed’s response. Chair Powell and senior Fed economists have disagreed with this judgment, but the FOMC is likely to make adjustments to its consensus statement nonetheless. It will likely return to saying that it will respond to “deviations” in both directions from maximum employment in normal times or at least water down the shortfalls language. It will also likely return to flexible inflation targeting (rather than flexible average inflation targeting) as its main strategy, though it is likely to retain the option to use a make-up strategy in some cases when the economy is at the ZLB. The FOMC could also pledge to respond forcefully to deviations of inflation in both directions, in line with the ECB’s recent strategy update. Neither change is likely to have an immediate impact on monetary policy.

It is less clear whether the FOMC will make significant changes this year to its communications practices. But participants have discussed two concrete proposals that could provide useful new information to financial markets if they are adopted later this year or in the future.

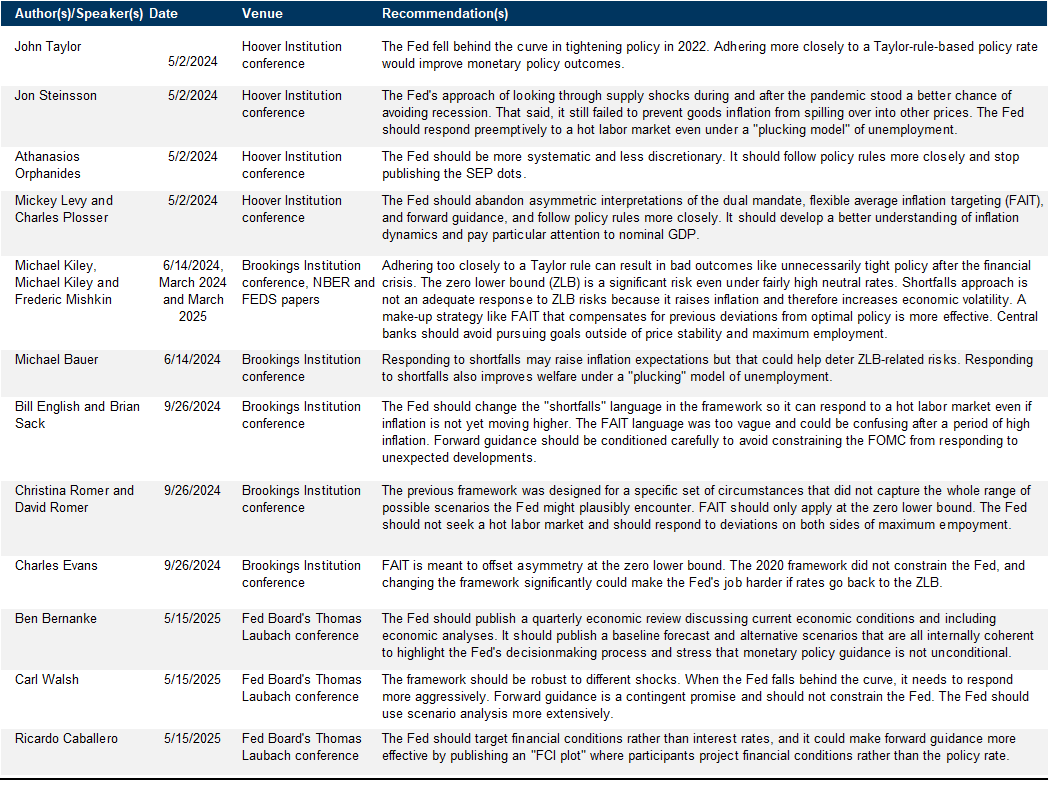

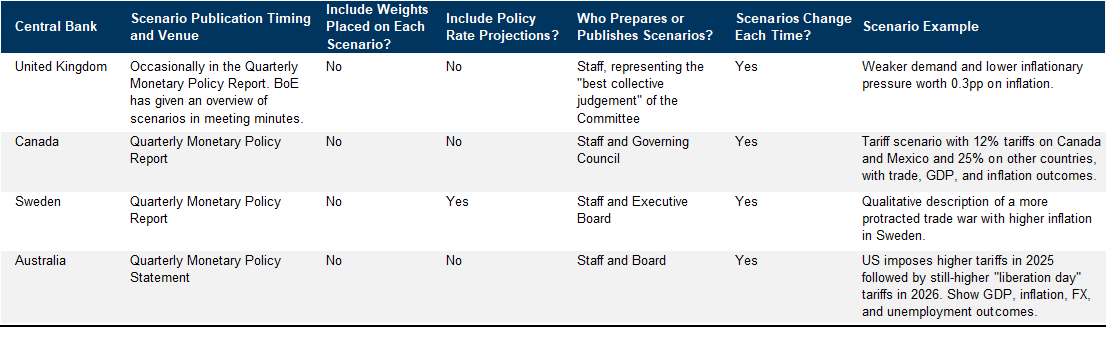

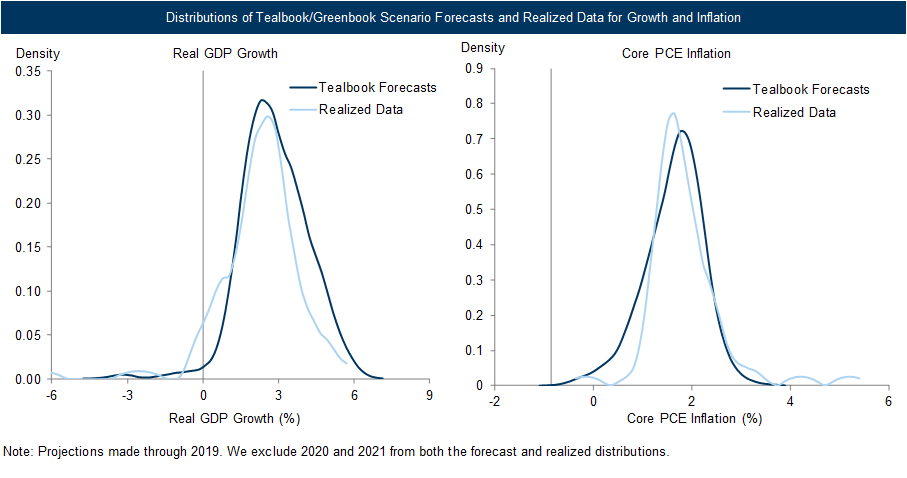

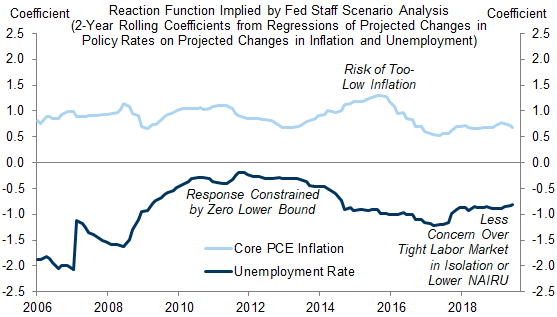

The first proposal is to provide alternative economic scenarios to highlight risks to the outlook. Some other central banks do this, but most do not show corresponding monetary policy paths that would help investors better understand the central bank’s current reaction function. The Fed staff already provides detailed alternative scenario forecasts in the Tealbooks, but they are currently only released to the public with a five-year delay. We find that these scenarios have provided context for how the reaction function—at least, the staff’s implied reaction function—has changed in different economic circumstances in the past. This context could be informative to investors if provided in real time, especially if FOMC participants began to provide alternative interest rate projections that corresponded to the staff’s alternative economic scenarios. That being said, the FOMC or staff might be reluctant to publish scenarios that are either politically sensitive or that draw attention to very negative economic outcomes.

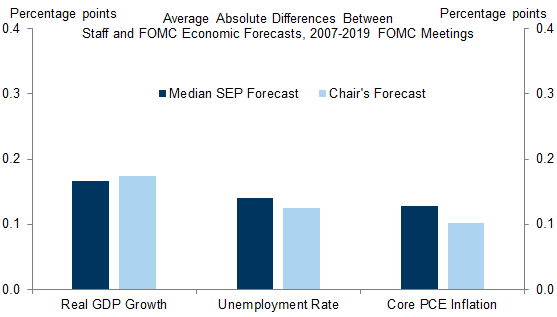

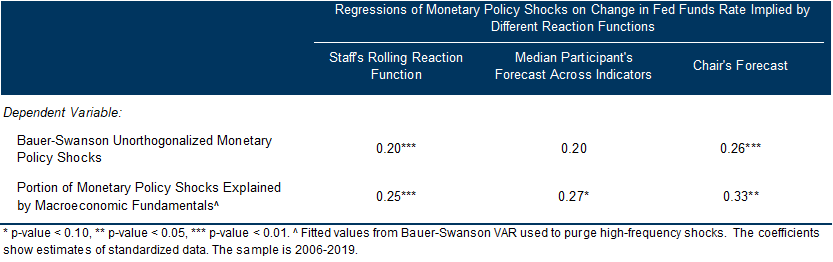

The second proposal is to link FOMC participants’ projections for the economy and interest rates, while keeping them anonymous. This would allow investors to see how each participant thinks the funds rate should be set under their economic forecast, rather than trying to infer a reaction function from committee-wide median economic and interest rate projections that often come from different individuals. We find that this information would likely be useful to investors—knowing the reaction function of the median participant inferred from their linked projections would have helped to predict monetary policy surprises in the past.

The Framework Review: Room for Innovation on Fed Communication

Rethinking the 2020 Framework Review

Room for Innovation on Fed Communication

Proposal #1: Publishing Alternative Scenarios

Proposal #2: Linking Individual Economic and Interest Rate Projections

New Fed Communications Could Provide Useful Information for Markets

Manuel Abecasis

David Mericle

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.