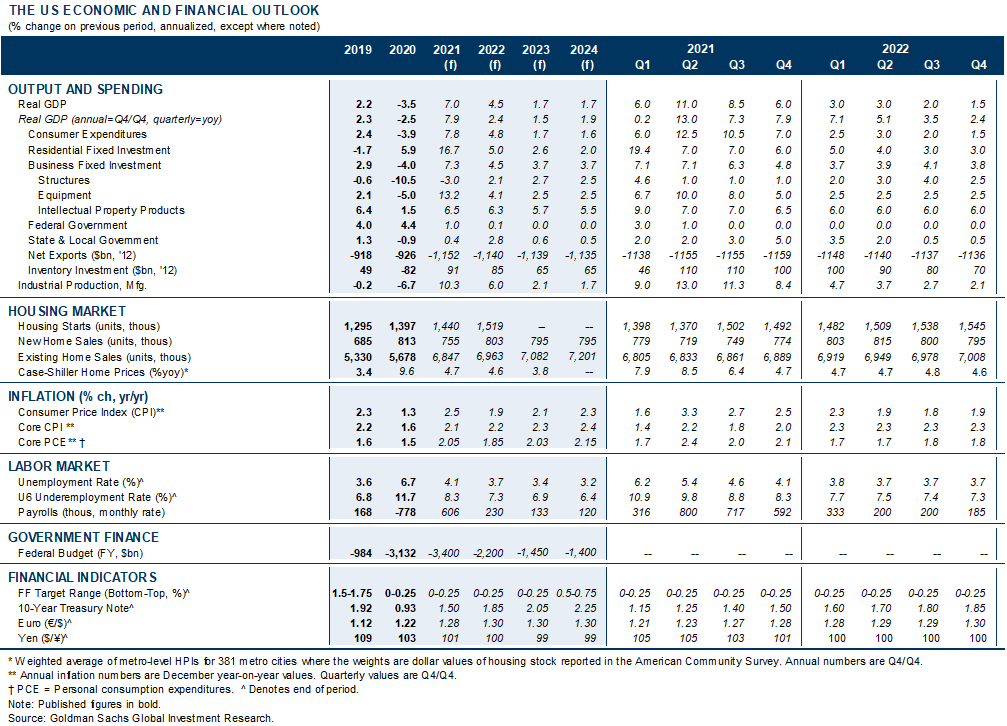

Core PCE inflation remains on track for a dead cat bounce above 2% this spring as we lap the peak pandemic declines in 2020. We have long expected a brief jump above 2% this spring, and Fed officials have already signaled that they will look past it.

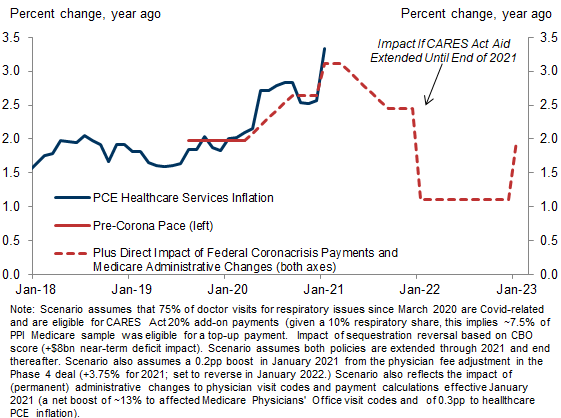

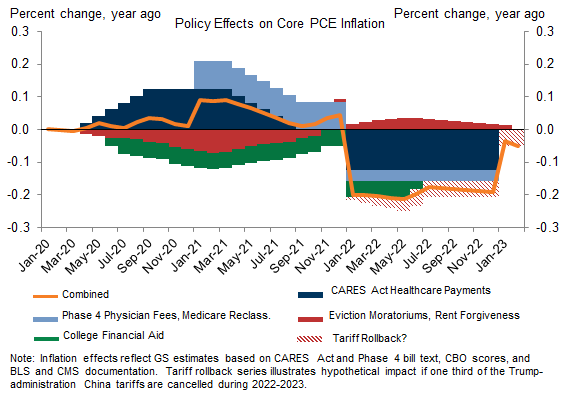

However, policy-related effects look likely to amplify the temporary boost from base effects, especially in the health care category that has been affected by recent Covid-relief legislation. We now expect the combination of base effects and policy effects to propel core PCE inflation up to 2.5% in April and to keep it above 2% even at year-end. However, we forecast payback from the expiration of these policies will culminate in a sudden 25bp drop in early 2022.

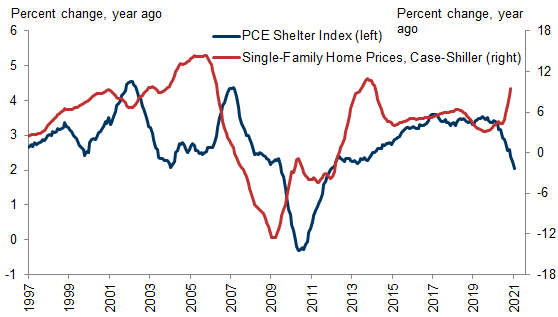

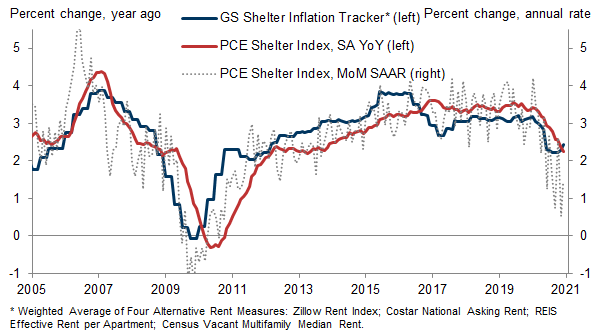

The other key to the outlook is shelter inflation. The shelter category is highly cyclical and it is not surprising that it has decelerated substantially, but this cycle has added unique pandemic-related effects to the usual cyclical factors.

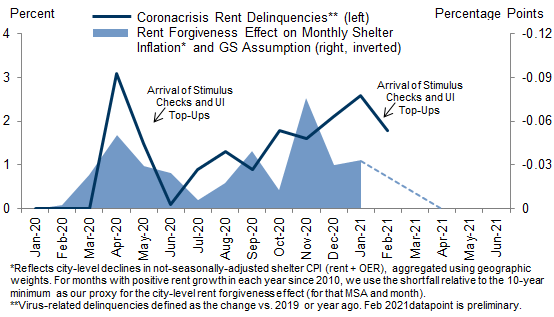

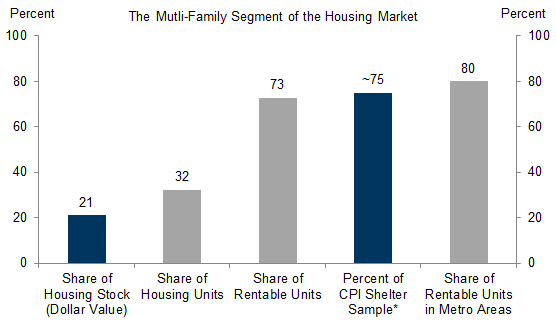

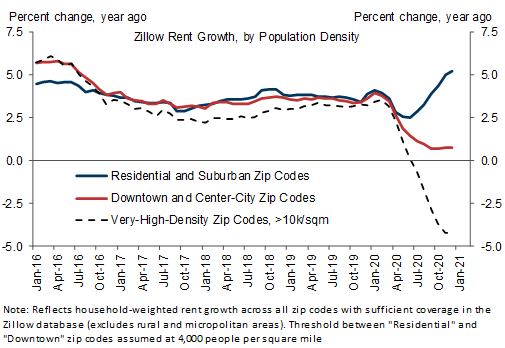

Two major pandemic effects are currently depressing shelter inflation but should raise it next year. First, flight from crowded urban apartment units is having an outsized impact on measured shelter prices, as they are overrepresented in the CPI shelter sample. Second, rent forgiveness has risen due to challenges in making rent payments and eviction moratoriums. Each factor appears to be depressing shelter inflation by 0.3pp. We expect shelter to decelerate further from 2% to a bottom of 1.6% at mid-year, but to then accelerate quickly to 2.2% at end-2021 and 3.4% at end-2022 as these pandemic effects fade and the labor market strengthens.

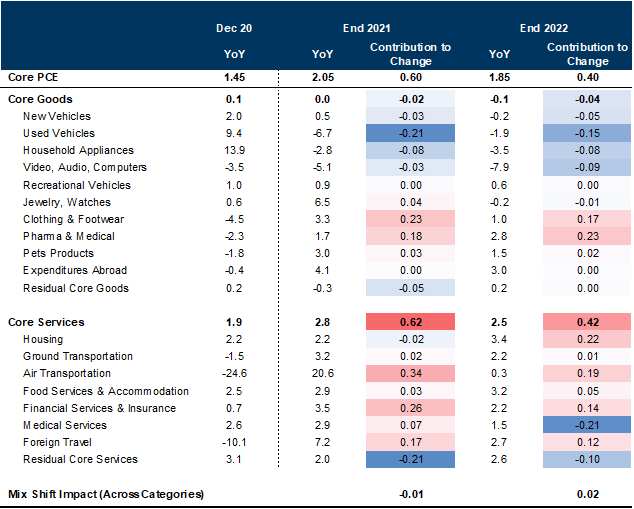

For core PCE inflation itself, we forecast a rise from 1.7% in January to a peak of 2.5% in April—exactly a year after the strictest lockdowns. But with healthcare policy swinging from a boost to a drag, we then forecast core inflation to fall back to 2.05% by year-end 2021 and to drop off sharply in early 2022. We forecast core inflation to end 2022 at 1.85% as the healthcare drag offsets tightening labor and rental markets, with the pace converging back toward 2% by early 2023.

Stepping back, the inflation volatility associated with so many idiosyncratic factors and measurement issues underscores the importance of monitoring underlying inflation measures—and of assessing evidence of overheating in the labor and product markets themselves.

Inflation Signal, Healthcare Noise

Urban Flight and the Missing Shelter Inflation

Which Housing Market Matters for Shelter Inflation?

Rockin' the Suburbs

Healthcare Policy Effects

Above-Target Inflation (But Don't Get Used to It)

Spencer Hill

- 1 ^ Historical relationships suggest the 5.2pp acceleration in home prices since the start of the coronacrisis would boost shelter inflation in 2020 and 2021, with a peak impact of around +0.5pp.

- 2 ^ We also do not believe the BLS will treat federal rental assistance programs as a discount relevant for the CPI shelter index, because the BLS collects information only about payments directly from the tenant to the owner/landlord.

- 3 ^ REIS and Costar vacancy rate measures have already risen 0.5pp and 0.4pp respectively.

- 4 ^ On our estimates based on the American Community Survey, the Housing Vacancy Survey, and the residential capital stock data from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA).

- 5 ^ Zillow rent indices are already constructed to be representative of the rental market

- 6 ^ Once the Zillow trends are fully reflected in the CPI data, which we expect by mid-year given the typical leading relationship.

- 7 ^ Put another way, urban flight is a flow effect, whereas vacancies are a stock measure.

- 8 ^ The Survey of Business Uncertainty suggests that employers expect that work-from-home will roughly triple in the post-pandemic economy,

- 9 ^ Paid by governments to healthcare providers, on a dollar-weighted basis. Specifically, CMS revised the pricing of some medical treatments in order to more accurately reflect physician time and operating costs. While some quantities were revised as well (e.g. time spent), the impact from an inflation perspective is a net increase in measured healthcare prices. These changes are not related to the pandemic.

- 10 ^ We don’t expect this headwind to prevent core inflation from rising further at this horizon (due to reopening and the anniversary of the depressed prices of the spring 2020 lockdowns). But the waning policy boost increases the likelihood that core PCE inflation falls back below 2% in the fall.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.