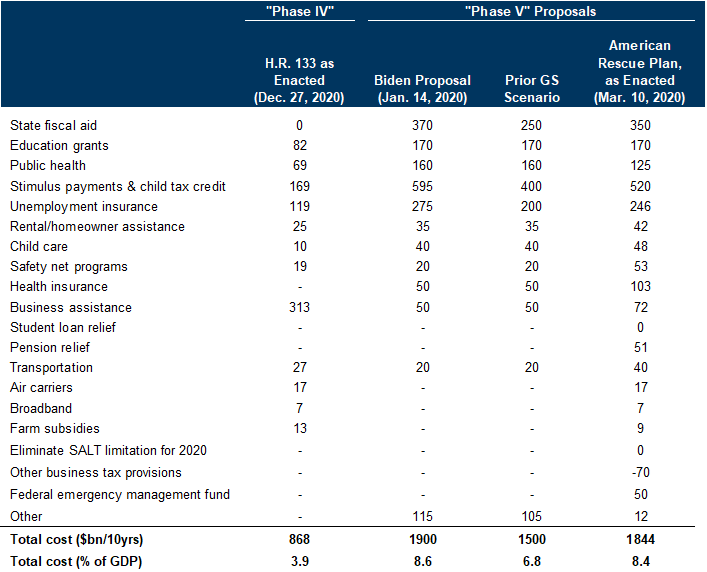

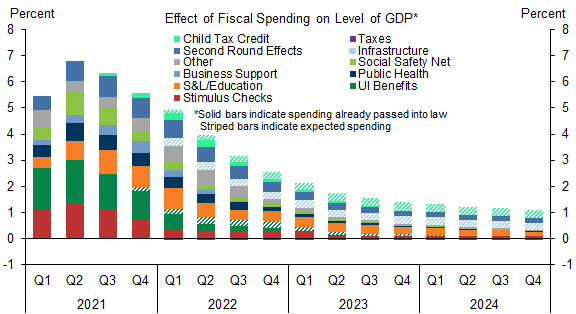

The American Rescue Plan (ARP) totaled $1.84 trillion (8.4% of GDP), somewhat larger than the $1.5 trillion (6.8%) we have been assuming in our economic forecast. Stimulus payments and child tax credits account for $120bn of the gap. The rest of the difference reflects items that should have less of a near-term economic impact, such as fiscal transfers to state and local governments, transit agencies, and pension funds.

We have made some changes to our longer-term fiscal assumptions in light of the new law. Specifically, we now assume that Congress will extend the larger child tax credit past its year-end expiration and that expanded unemployment insurance eligibility and benefit duration will last through 2022.

Details on the next fiscal package are scarce. At this point we expect the White House to propose at least $2 trillion for infrastructure, though this could reach as much as $4 trillion if the proposal extends to other areas (e.g., child care, health care, or education). Increases in the corporate and capital gains tax rates look likely to finance a portion of this, though we believe it will be difficult for Congress to agree on more than around $1 trillion in such offsets.

While the next major fiscal proposal might come with a large headline number, it is likely to have a much smaller impact on growth in 2021 and 2022, as the spending will be more evenly distributed over several years and some of it will likely reflect spending that would have happened in any case. Offsetting tax increases could also incrementally dampen the effects.

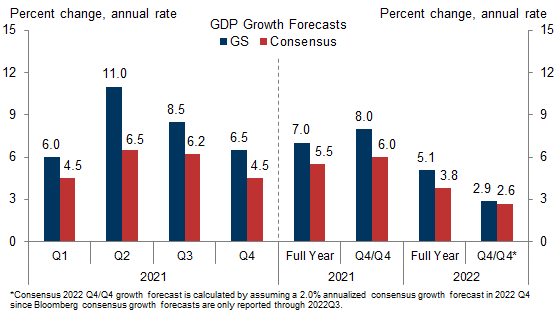

In light of the larger fiscal package just enacted, we now expect slightly higher GDP growth of +6% / +11% / +8.5% / +6.5% in 2021Q1-Q4 which implies +7.0% in 2021 on a full-year basis (vs. +5.5% consensus) and +8.0% on a Q4/Q4 basis (vs. +6.0% consensus).

As we now expect a somewhat slower drop-off in fiscal support in subsequent years, we have also raised our GDP growth forecast in 2022 by 0.6pp to +5.1% on a full-year basis (vs. +3.8% consensus) and by 0.5pp to +2.9% on a Q4/Q4 basis (vs. +2.6% consensus).

We have also nudged down our unemployment rate forecast and nudged up our core PCE forecast. After these changes, we view the first hike in the funds rate as a close call between the second half of 2023 and the first half of 2024, and the timing will depend critically on where FOMC participants at that time put the core PCE liftoff threshold. The summary of economic projections provided at the March FOMC meeting next week will provide insight into the FOMC’s reaction function, and we will update our Fed call in our March FOMC recap.

More Spending, More Growth

Alec Phillips

Joseph Briggs

David Mericle

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.