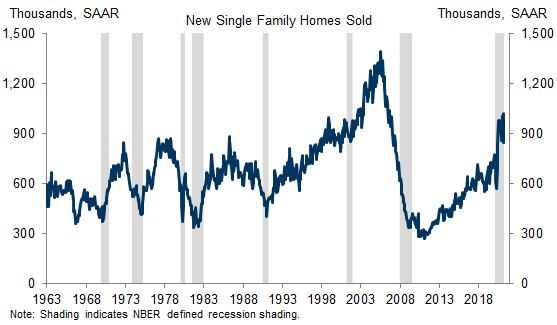

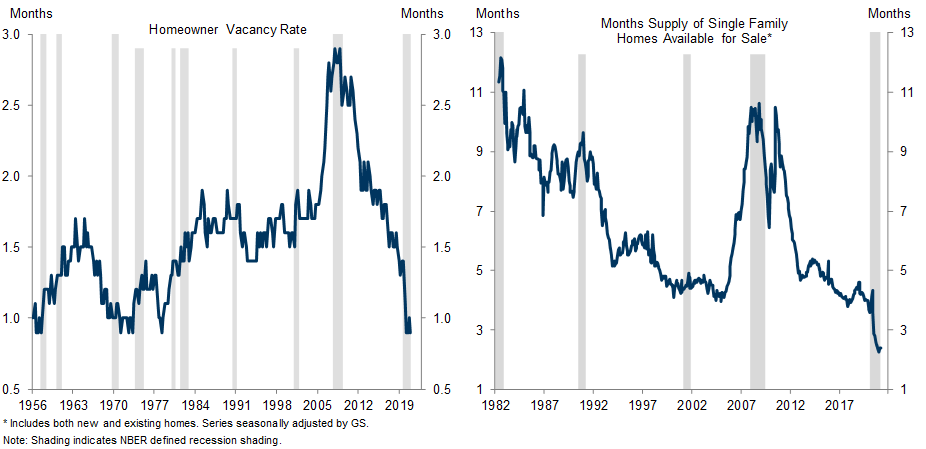

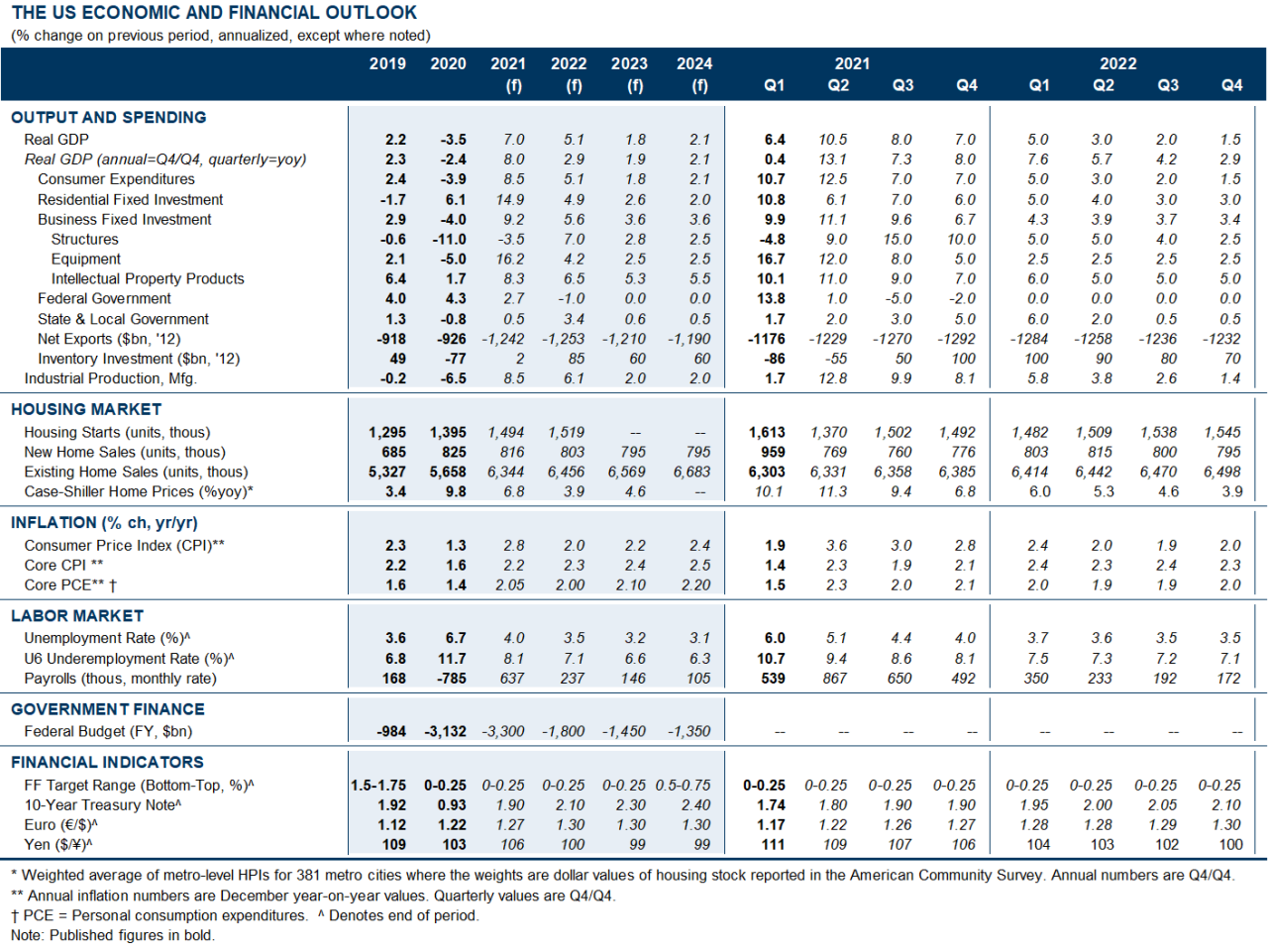

The US housing sector is on fire. New home sales and housing starts both reached their highest levels since 2006 in March, and red-hot demand has brought the supply of homes available for sale down to the lowest level since the 1970s. Competition among buyers for a dwindling national housing supply has sent prices 12% higher over the last year, but so far this has done little to reduce the severe imbalance between supply and demand in the housing market.

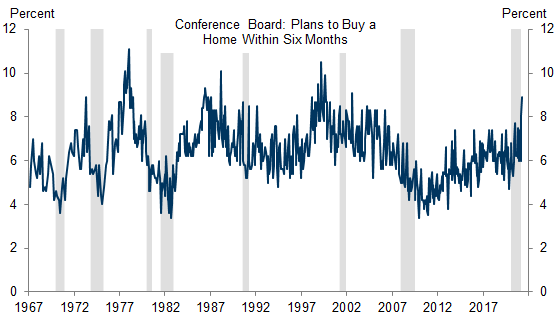

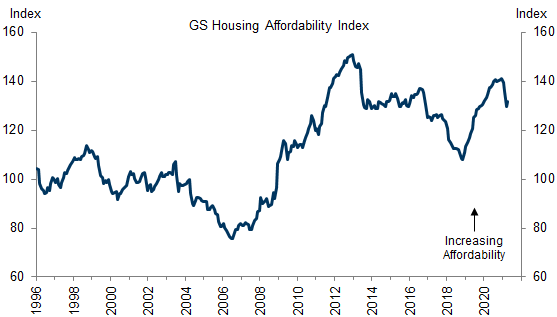

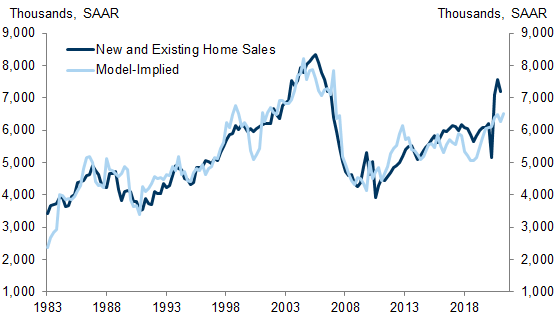

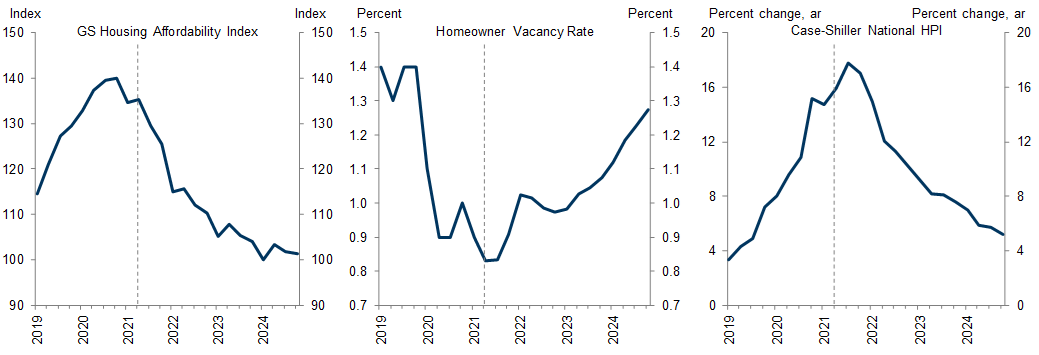

Strong demand for housing looks sustainable. Even before the pandemic, demographic tailwinds and historically-low mortgage rates had pushed demand to high levels. A shift in preferences during the pandemic caused demand to spike, and consumer surveys indicate that household buying intentions are now the highest in 20 years. This is especially impressive because unlike in the mid-2000s, mortgage lending standards have remained fairly tight. With demographic trends still strong, mortgage rates very low, housing affordability still high, and household wealth as a share of income at the highest level in US history, demand should remain strong.

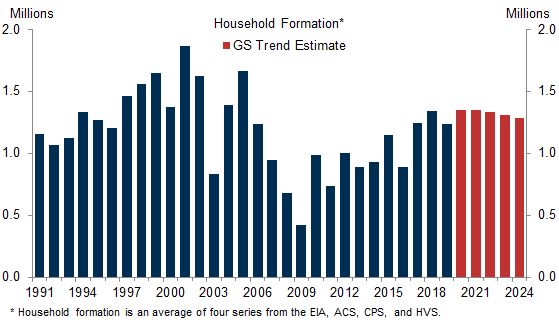

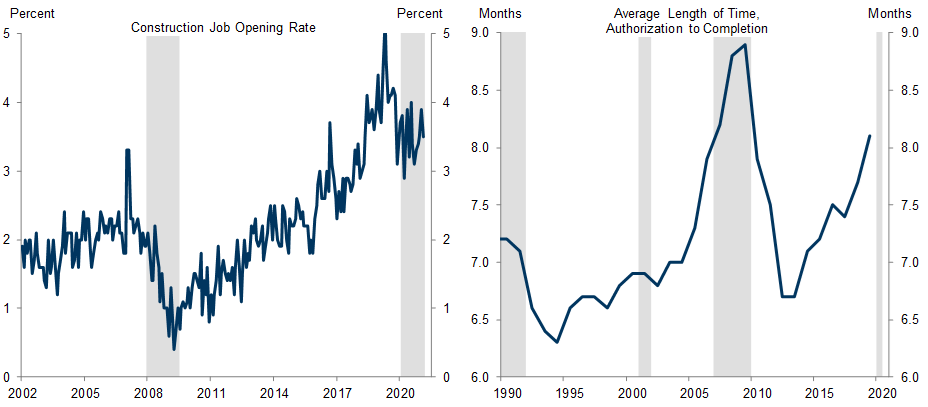

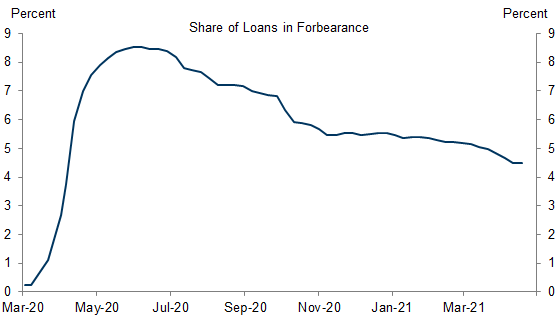

The supply picture offers no quick fixes to the shortage of available homes. Homebuilders are again facing headwinds that were already present before the pandemic, especially a lack of available plots to build on and a lack of construction workers. These constraints are likely to limit the pace of annual homebuilding to around 1.5mn in coming years. The expiration of pandemic-related forbearance provisions later this year should put some additional homes on the market, but this will only modestly alleviate the lack of supply.

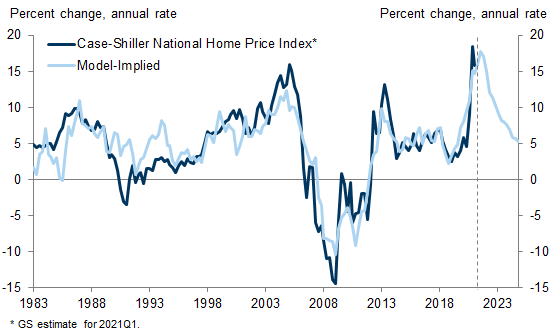

The resulting picture is one of a persistent supply-demand imbalance in the years ahead. To forecast what this means for home prices, we estimate a model that jointly considers supply, demand, affordability, and home prices. The model suggests that rising prices will only gradually reduce affordability enough to dampen demand and mitigate the supply-demand imbalance. As a result, the model projects double-digit price gains both this year and next.

House price growth does not directly enter the inflation statistics, but it does spill over to rent inflation, as economic intuition would suggest. This is one reason we expect an acceleration in the shelter category this year and next to provide a meaningful boost to core inflation.

Housing on Fire

The Demand Picture: Sustainable Strength

The Supply Picture: No Quick Fixes to the Housing Shortage

Home Prices: A Multi-Year Boom

Ronnie Walker

- 1 ^ Changes in surveying procedures and response rates during the pandemic appear to have distorted the Housing Vacancy Survey for most of 2020, but the impact appear to have been mostly unwound by 2021Q1 (see Census FAQ here).

- 2 ^ Because individual household formation series are noisy, we average data from the monthly Housing Vacancies and Homeownership (HVS) survey, the annual American Community Survey (ACS), the March Current Population Survey (CPS), and estimates based on residential electricity meter data from the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The household formation data for 2020 that is already released points to a wide range of values, in part because of pandemic-related distortions to survey procedures (see previous footnote). We assume that household formation for the year as a whole remained firm, in part because of the rapid pace of home sales (Exhibit 1) and surveys of homebuyers.

- 3 ^ Apurva Gundaria and Marty Young, “The Credit Line: US Housing Remains Relatively Affordable,” 2021.

- 4 ^ While the model is well below the actual level of 2021Q1 home sales of 7.2mn, the current pace likely reflects some pent-up demand from sales that didn’t occur early in the pandemic: the gap between the model and actual is cut in half on a 4QMA basis.

- 5 ^ For discussion on the impact of consumer expectations and credit availability on home prices, see Brian Chen and Marty Young, “US Daily: Will Home Price Growth Slow Further?” 2019.

- 6 ^ We assume that inflation expectations – an input to our home prices model – evolve in a manner consistent with our inflation forecasts, as outlined in Joseph Briggs, “US Daily: A Top-Down Checkup On Our Inflation Forecast,” 2021. We assume that credit availability and surveys of consumer demand remain roughly unchanged.

- 7 ^ David Mericle, “US Daily: Shelter Inflation Likely to Rise a Bit Further,” 2014.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.