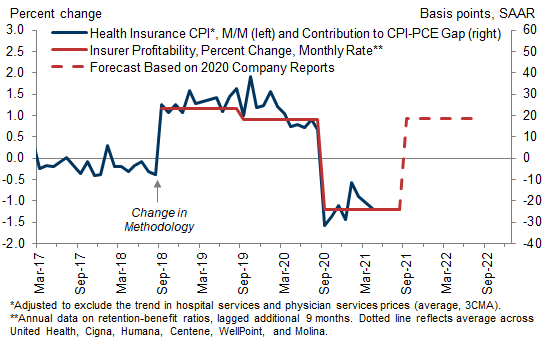

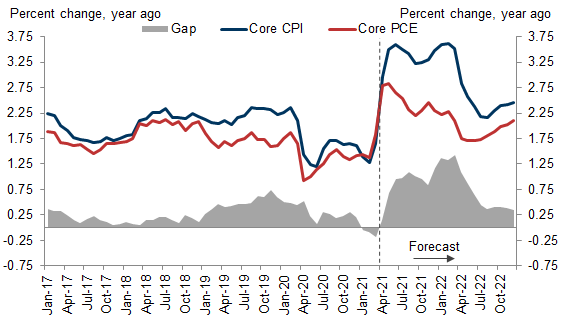

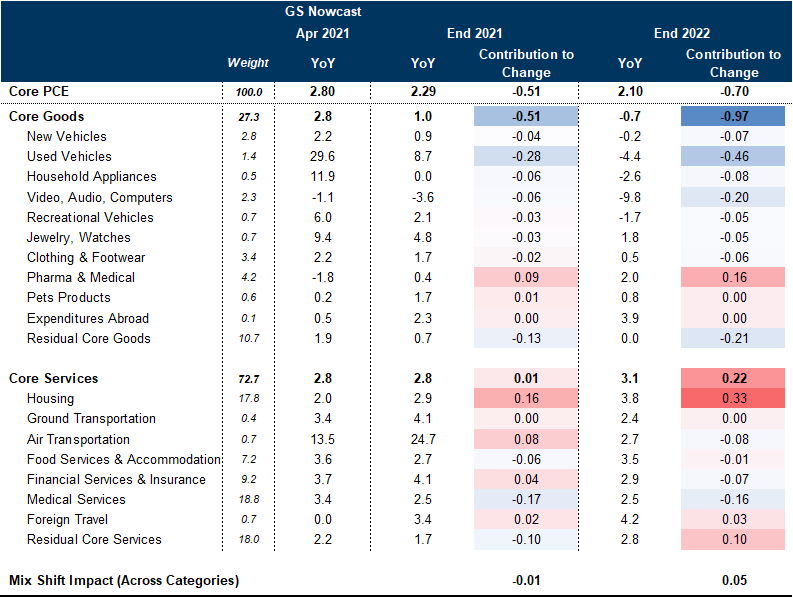

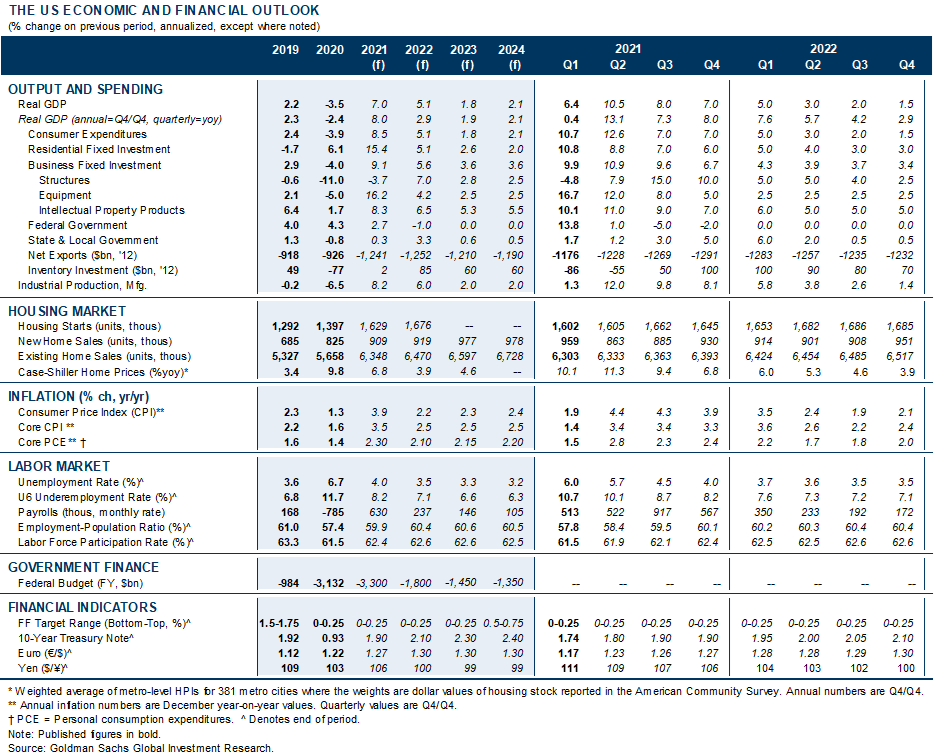

We are boosting our core CPI forecasts significantly further and now forecast a peak of 3.6% year-on-year in June, followed by 3.5% at end-2021 and an average of 2.7% in 2022. The latest revisions reflect a further increase in used car auction prices and downward revisions to auto production schedules, as well as signs that health insurance prices will rise sharply this fall.

Our core PCE inflation forecast remains at 2.8% in April/May, followed by 2.3% at end-2021 and an average of 2% in 2022. The CPI-PCE gap is so large because the weights of both used cars and shelter are much bigger in the core CPI than in the core PCE, and because health insurance prices are not included in the PCE (which instead focuses on economy-wide medical costs).

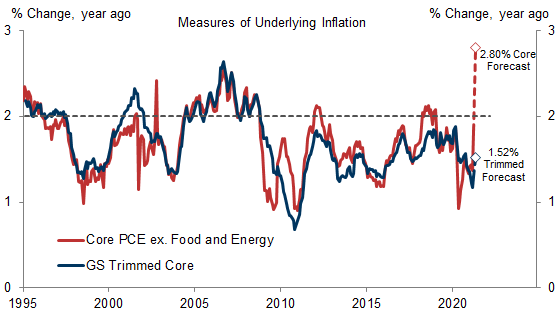

More broadly, the recent inflation news has not meaningfully altered our relatively relaxed medium-term view because much of it reflects such obviously temporary factors. The best illustration is that the GS trimmed core PCE index—which systematically excludes the most volatile core price changes—only rose an estimated 1.5% year-on-year in April, 1.3pp below the official core PCE rate.

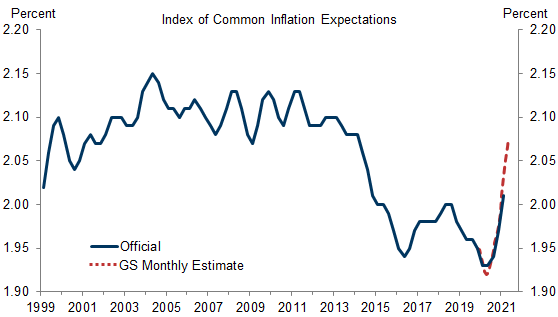

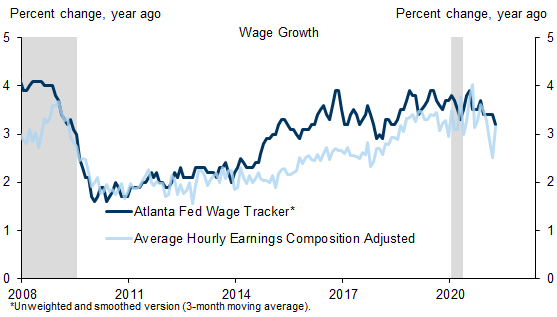

Our concern about second-round effects from the short-term price surge remains limited so far. Although inflation expectations have moved up, our replication of the Fed's reference measure is still below the levels seen in the 2001-2007 expansion. Meanwhile, the weakness in labor supply that is evident from April's large wage increase (and from the surge in vacancies) should end as the pandemic recedes further and the $300/week unemployment benefit top-up expires on September 6 (or earlier, at least in many Republican-controlled states).

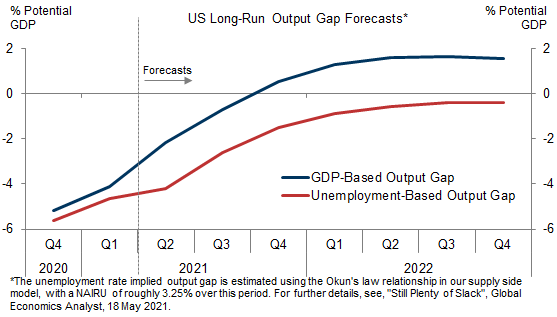

Ultimately, the biggest question is whether the economy will overheat, i.e. whether output and employment will rise substantially above potential. We don't expect this because the starting point is one of sizable slack—especially if we consider not just GDP-based but also employment-based measures of the output gap—and because growth is likely to slow from its current rapid pace as the fiscal impulse turns negative next year.

Mind the Gap: Core CPI Surges, But Core PCE Should Still Average 2% in 2022

Jan Hatzius

Spencer Hill

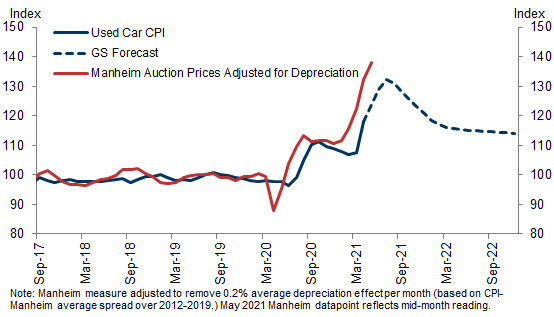

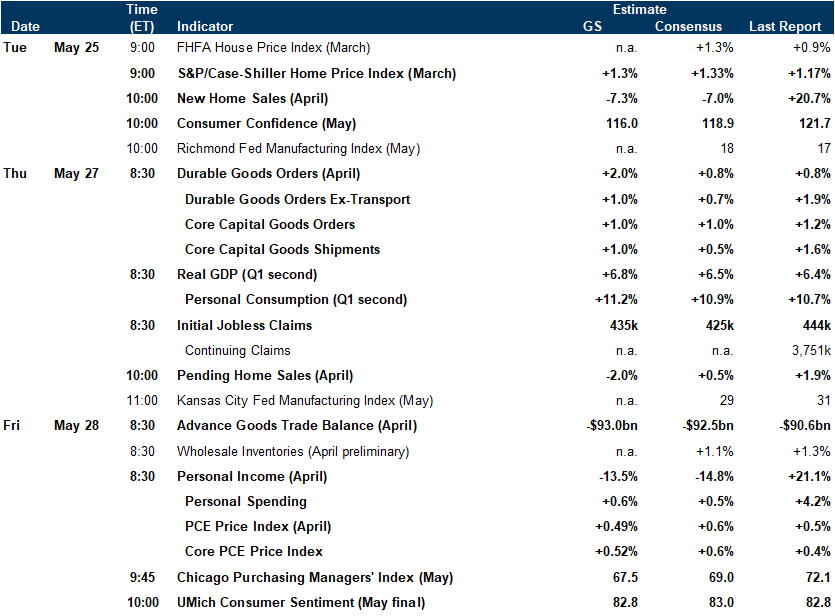

- 1 ^ While we await publication of full-month data, we are penciling in a nearly 5% increase in the May Used Car CPI (see Exhibit 1), and we expect a further 4-7% increase before prices peak in June or July, given the lags between auction prices and the inflation statistics. Many of the more dramatic swings in the Manheim measure historically, including the April 2020 collapse, were not fully reflected in the subsequent CPI data, which is based on different source data. The CPI measure also removes an upward bias from depreciation, in order to maintain constant vehicle quality over time.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.