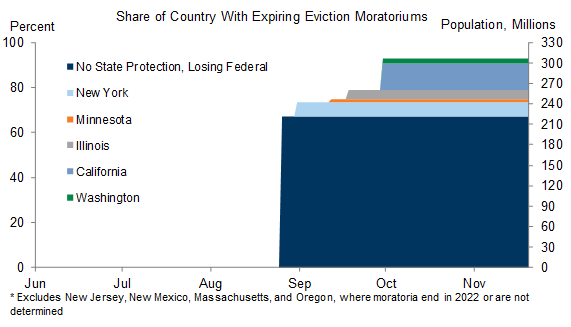

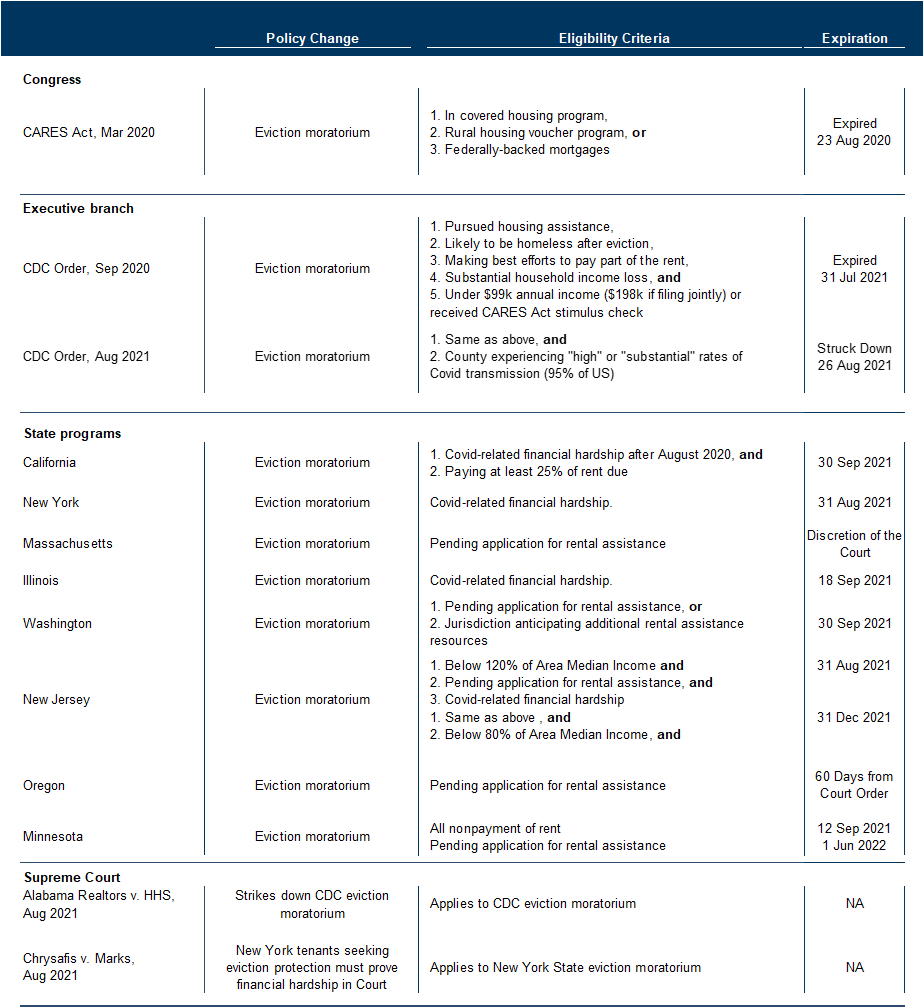

With the Supreme Court striking down the federal eviction moratorium and with most state-level restrictions set to expire over the next month, we explore how sharply evictions could rise under current policy, and we estimate the potential impact on the economy.

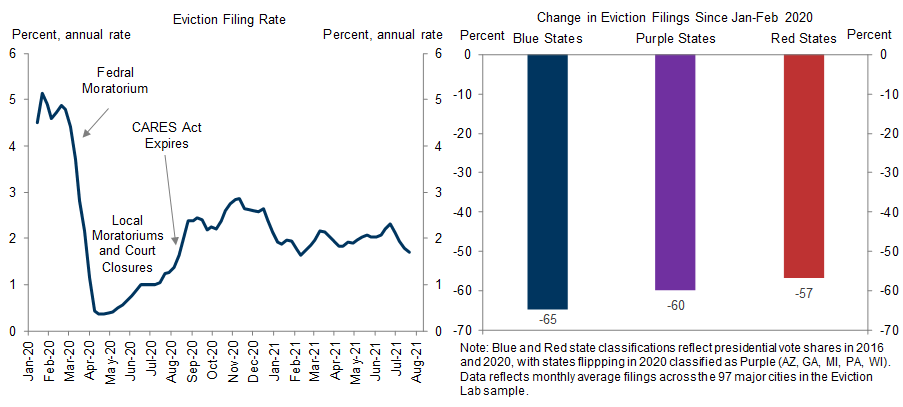

Despite a severe recession, evictions actually declined during the coronacrisis due to the national eviction moratorium, with eviction filings declining 65% in Blue states and 61% nationwide.

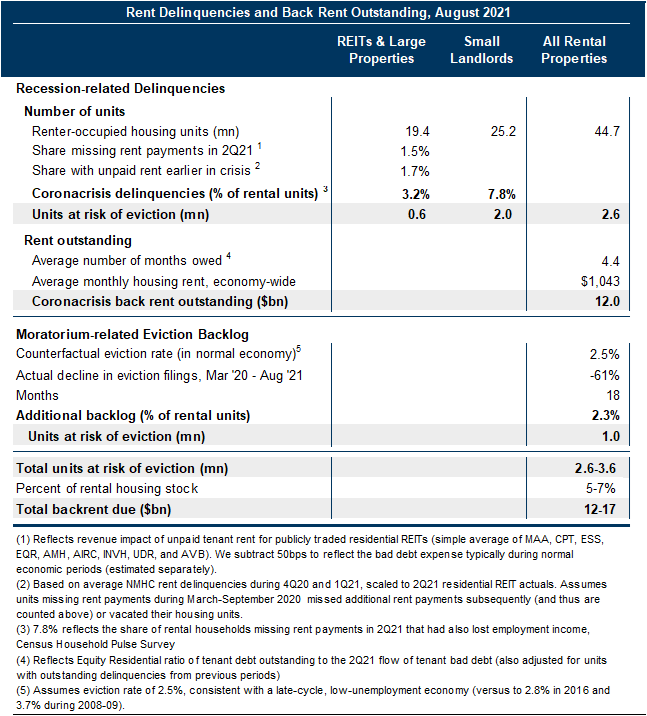

Using rent delinquency data from real estate companies, the National Multifamily Housing Council, and the Census Pulse survey, we estimate 2½-3½ million households are behind on rent, with $12-17bn owed to landlords.

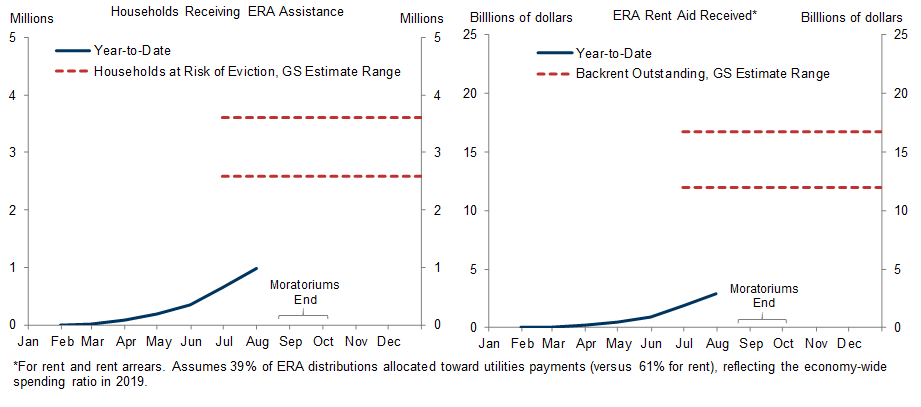

Despite the $25bn dispersed from the Treasury to state and local governments, the process of providing these funds to households and landlords has been slow. Only 350k households received assistance in July, and at this pace, we estimate 1-2 million households will remain without aid and at risk of eviction when the last 2021 eviction bans expire on September 30.

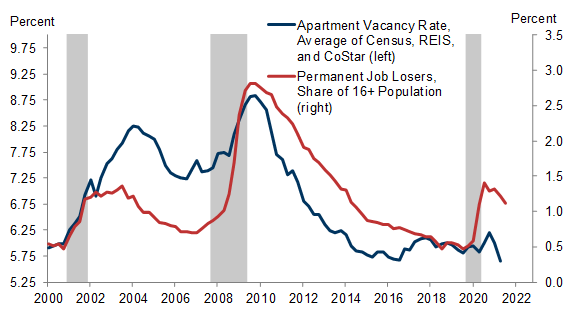

The strength of the housing and rental market suggests landlords will try to evict tenants who are delinquent on rent unless they obtain federal assistance. And evictions could be particularly pronounced in cities hardest hit by the coronacrisis, since apartment markets are actually tighter in those cities. Taken together, we believe roughly 750k households will ultimately be evicted later this year under current policy.

Our literature review indicates a small drag on consumption and job growth from an eviction episode of this magnitude, but the implications for covid infections and public health are probably more severe.

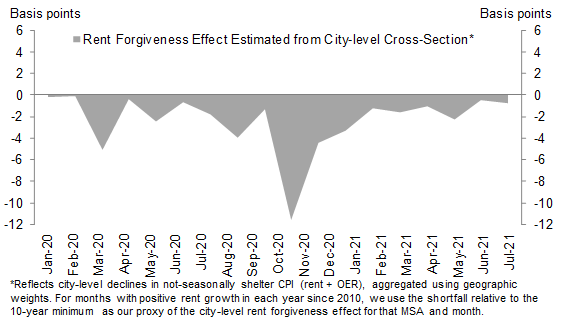

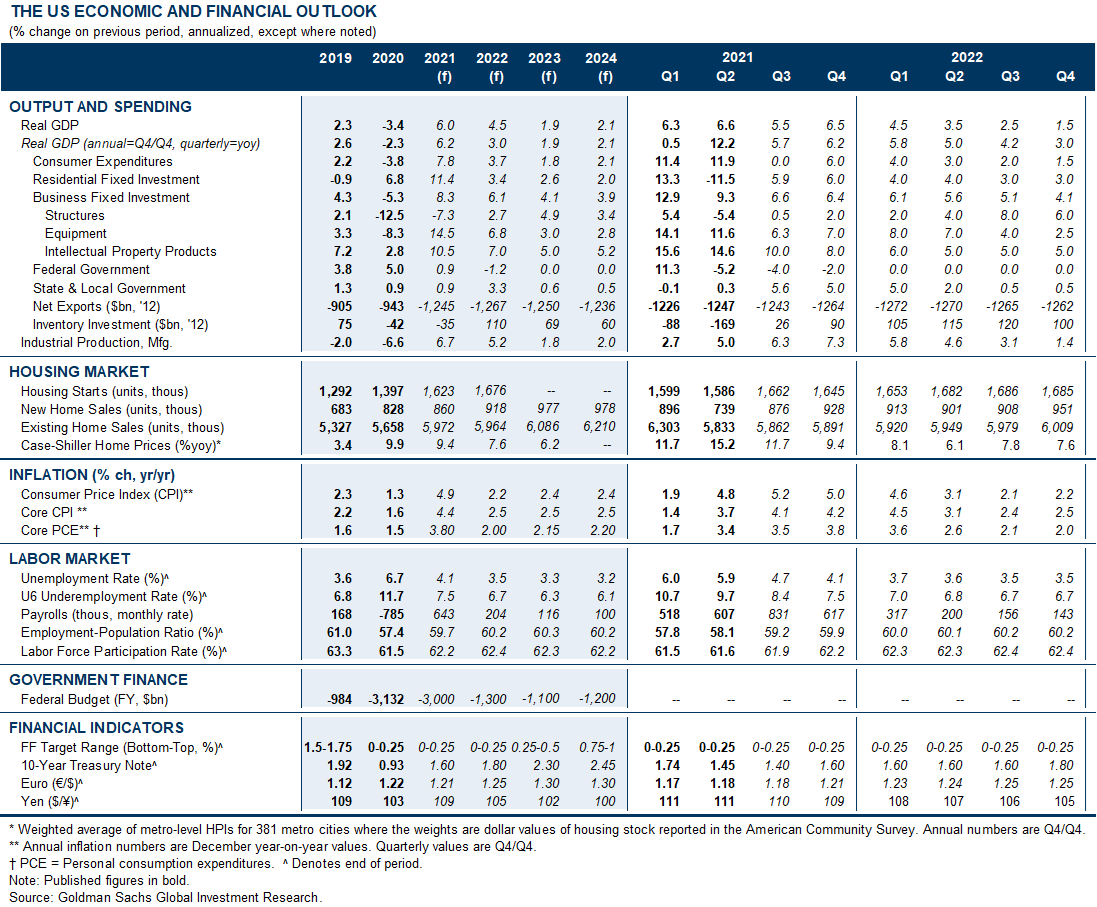

The end of the moratoriums would also exert downward pressure on shelter inflation as vacancy rates rise. Under our baseline estimates, post-moratorium evictions will raise the vacancy rate by about 1pp, which on its own would lower shelter inflation by 0.3pp in 2022, partially offsetting the intense upward pressure from the housing shortage.

Evictions and the Economy as the Moratoriums End (Hill)

A Rental Policy Shock

Economic Impact of the Moratoriums

Today’s Eviction Backlog

Yet Another Bottleneck

Economic Consequences

Spencer Hill

- 1 ^ The Biden administration and the CDC had issued a new eviction moratorium on August 3rd after the previous version expired on July 31. The Biden/CDC moratorium covered roughly 90% of housing areas as the prior federal ban.

- 2 ^ The direct impact of lockdowns and court closures also likely contributed.

- 3 ^ Another possible growth channel is the reduced consumption and investment activity of landlords, property managers, and residential REITs—for whom the moratoriums reduced rental income (due to longer average delinquency spells among tenants). However, with opportunities for consumption and investment already significantly depressed by the pandemic, we believe the incremental drag from property-owner cash flow constraints were small or insignificant for the economy as a whole.

- 4 ^ The Philly Fed estimated nearly 1 million units with back rent still owed in March 2021, the Census Household Pulse survey currently indicates roughly 6 million households behind on rent, and Stout estimates an even higher number (between 7-14 million households).

- 5 ^ For large property managers, we estimate the current pace of delinquencies based on the bad debt expense reported during Q2 earnings season. This line item represents the net share of quarterly rental revenues still uncollected ~3 weeks after the end of the quarter. At 2.0% on average across residential REITS, this would be consistent with 2 of every 100 units missing rent payments for April, May, and June 2021 (on a revenue-weighted basis). Because some rental units missed payments earlier in the crisis but nonetheless made all three rent payments in Q2, this 2.0% figure likely understates the total delinquencies. Accordingly, we add another 2.3pp based on 1Q21 and 4Q20 NMHC rent delinquency trend—which has the benefit of a longer history but the drawback of only tracking payments for the most recent month. Together, we estimate that 4.3% of housing units are delinquent and at risk of eviction among large property managers, or 0.8mn units.

- 6 ^ Lacking timely data from smaller “mom and pop” landlords, we analyze and adjust consumer survey data to estimate delinquencies in the remaining 25mn units of the rental market. Because some rent payments are delayed even in normal economic times and because landlords generally do not evict tenants whose debts are small or short-lived, we identify tenants in the survey data who are not current on rent payments AND lost employment income during the pandemic recession—7.8% of households based on the Census Pulse survey. On a weighted-average basis, this implies 2.6mn households at risk of eviction nationwide because of the pandemic.

- 7 ^ We assume a counterfactual eviction rate of 2.5%--based on the low-unemployment economy heading into the pandemic—and we calculate this backlog by applying the actual decline in eviction filings using the Eviction Lab dataset.

- 8 ^ $46bn of Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA) funding under the CARES and ARP Acts is available to keep eligible, lower-income tenants in their homes.

- 9 ^ Additionally, only lower-income households are eligible for federal aid, with the threshold set at 80% of median area income.

- 10 ^ The magnitude of these estimates span a wide range, from 1pp to 22pp; we favor the methodology of estimates towards the lower end of this spectrum that estimate the causal relationship.

- 11 ^ To estimate the impact of resuming rent payments on consumption, we first take our estimates of the number of units that skipped payments in Q2 and multiply them by the average monthly housing rent to get a dollar value of skipped rent payments. To get the annualized consumption effect, we apply marginal propensities to consume (MPCs) from previously-estimated ranges to the annualized dollar value of rent payments and scale it by Q2 annualized Personal Consumption Expenditures. We use relatively high MPCs to reflect our assumption that households who are behind on rent are at the lower end of the income distribution, and therefore consume a higher share of their income. Using this method, we estimate that the end of eviction moratoriums over the coming months will result in an annualized 26bps drag on consumption in Q4.

- 12 ^ Controlling for the unemployment rate to prevent omitted variable bias, we estimate a 1pp increase in the rental vacancy rate lowers year-on-year shelter inflation by 0.3pp (p-value = 0.00).

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.