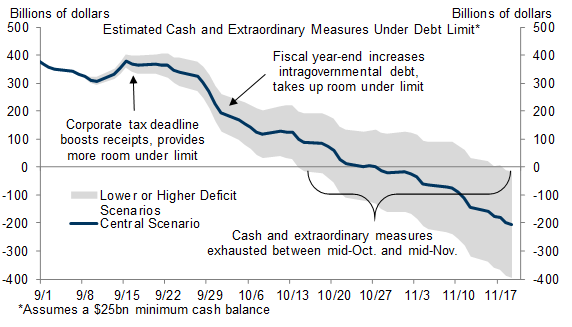

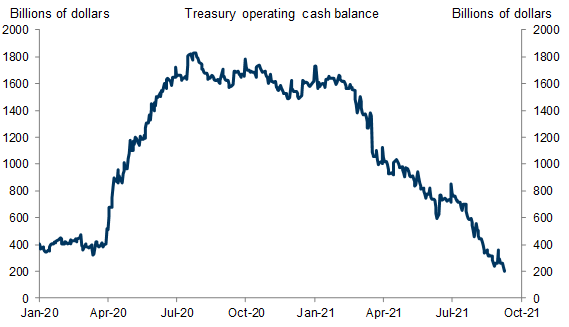

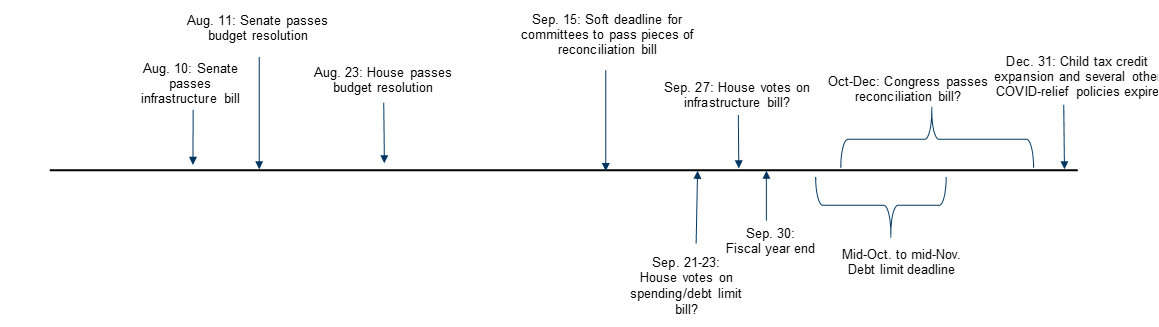

We estimate Congress will need to raise the debt limit by mid-October, though it is possible the Treasury might be able to operate under the current limit until late October. It is possible, though not likely, that the Treasury might be able to continue to make all scheduled payments until sometime in early November if the deficit is smaller than expected.

There are two procedural routes congressional Democratic leaders can take to raise the debt limit, but neither is easy. Democrats would not need Republican support if they use the reconciliation process, but they would face a number of other procedural and political disadvantages. Attaching a debt limit suspension to upcoming spending legislation looks more likely, but this might not succeed and could lead to a government shutdown.

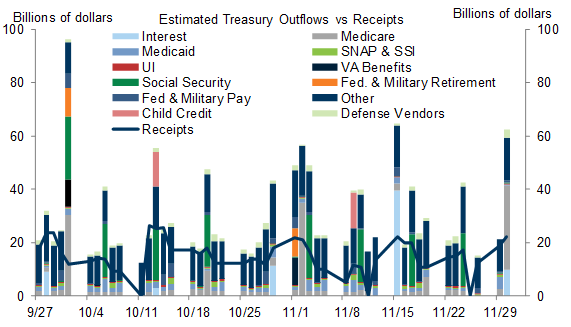

A failure to raise the debt limit would have serious negative consequences. While it seems likely that the Treasury would continue to redeem maturing Treasury securities and make coupon payments, if Congress does not raise the debt limit by the deadline the Treasury would need to halt more than 40% of expected payments, including some payments to households.

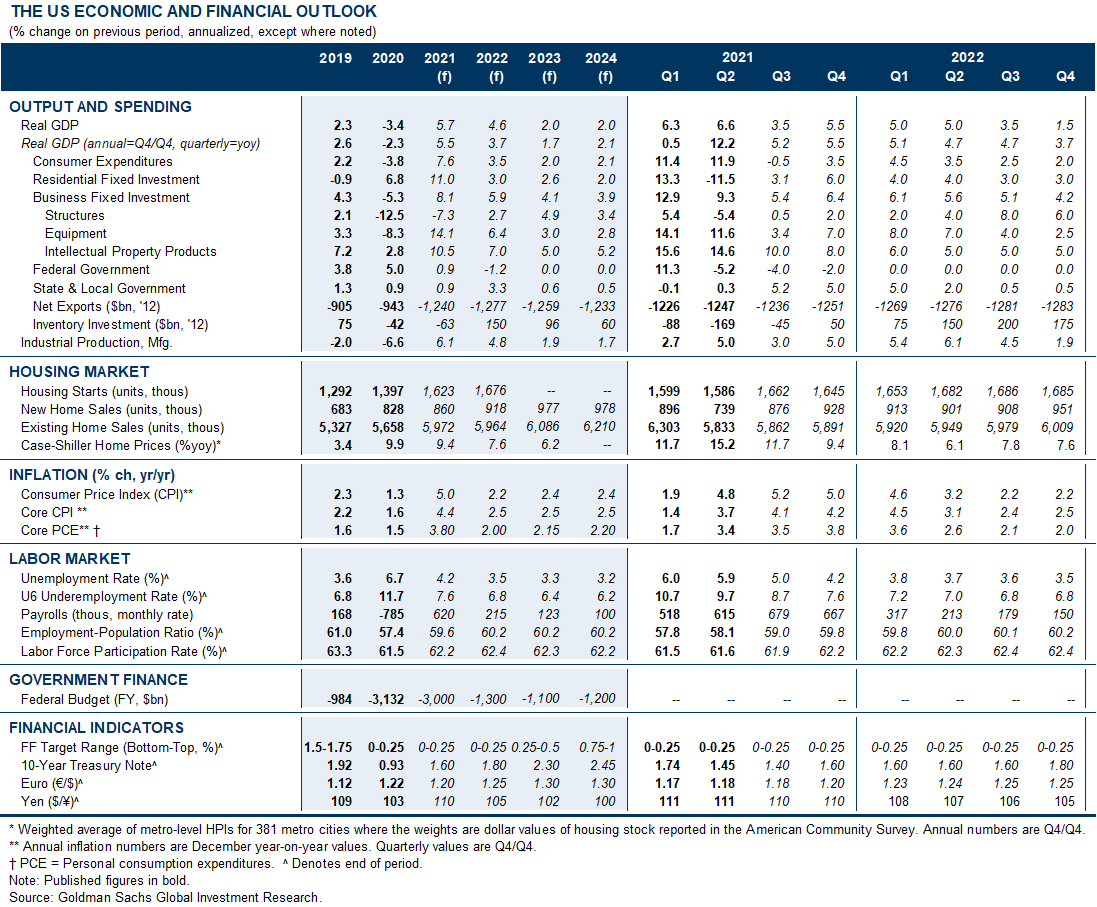

Beyond the direct impact, the debt limit could also affect the medium-term outlook for fiscal policy. We already expect the Democratic fiscal package to be scaled back from the proposed $3.5 trillion/10 years in new spending to $2.5 trillion, offset by around $1.5 trillion in new tax revenue. While there is not necessarily a direct linkage between the debt limit and the fiscal package, the more these issues become entangled the more pressure there may be from centrist Democrats to scale back the size of the fiscal package.

The Debt Limit Looks Riskier Than Usual

An October Debt Limit Deadline

There Is No Easy Way Out

A Government Shutdown Is a Very Real Possibility

The bill passes, resolving both issues. The simplest outcome would be for Republicans to allow the continuing resolution/debt limit bill to pass. This could technically happen without Republican support, if they voted against the bill but did not filibuster it—in that case, it could pass with 51 votes. The debt limit increase might also be structured to allow the President to raise or suspend the debt limit, subject to a resolution of disapproval that would block it. Congress could pass such a resolution, but the President could veto it, leaving the debt limit increase intact. Congress used a version of this in 2011 to end the debt limit standoff that year. While such a scenario is possible again this year, it does not look like the most likely outcome, in our view.

Republicans oppose the package, and Democratic leaders extend spending authority without the debt limit. As noted above, the exact date on which the Treasury will no longer be able to satisfy all its obligations is unclear, but it is probably not October 1. If Republicans are willing to support an extension of spending authority but not a debt limit increase, Democratic leaders could have a difficult time keeping the two issues joined if the debt limit is not seen as immediately pressing. Instead, a short-term extension of spending authority could push the issue until later in the month.

Republicans oppose the package but Democrats keep them tied together. In this scenario, a shutdown would become likely. This would be more likely if the debt limit deadline turns out to be earlier in October than expected.

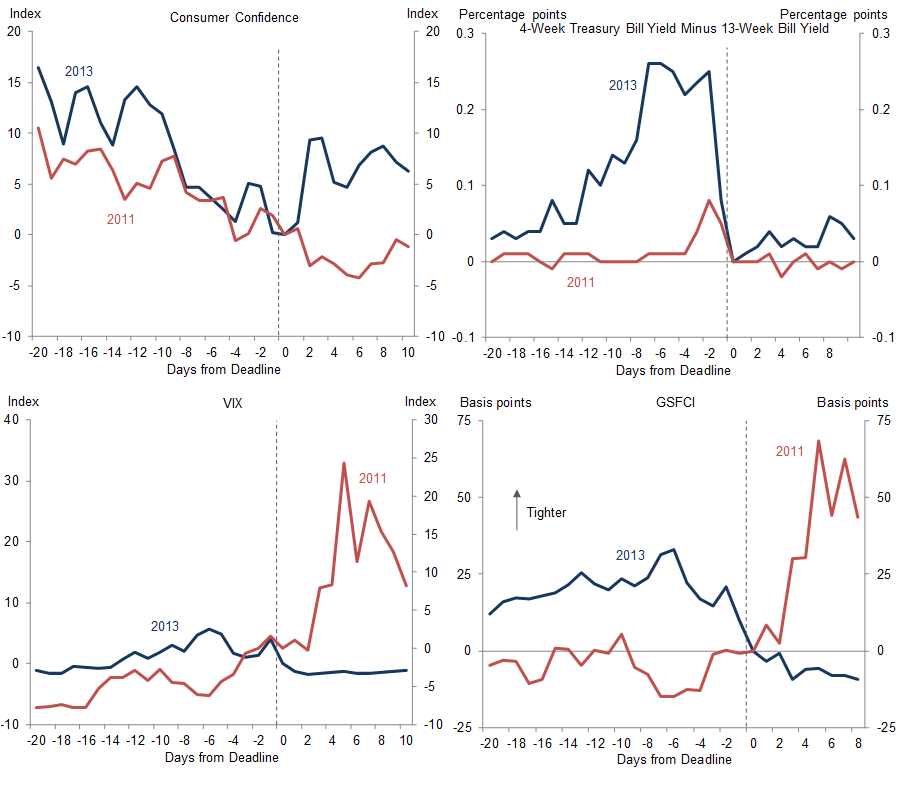

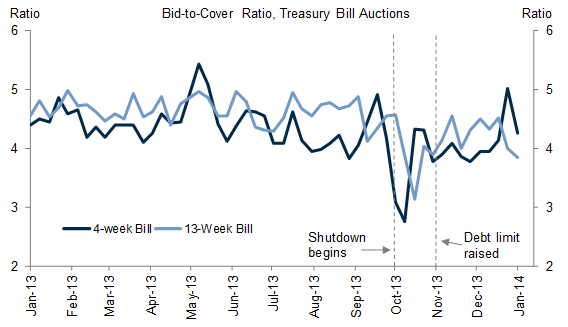

The Riskiest Debt Limit Deadline in a Decade

Missing the Deadline

In 1957, prioritization appears to have occurred following expiration of a temporary increase in the debt limit. As the federal government began to run a budget deficit following expiration, the Treasury was forced to delay payments to federal contractors.

In 1985, ahead of the debt limit increase that year, the General Accounting Office (GAO, now known as the Government Accountability Office) advised the Senate Finance Committee that the Treasury had the authority to choose the order in which to pay obligations.

In early 1996, the Treasury indicated that failure to raise the debt limit would result in failure to make Social Security payments, though Congress provided relief before any delay occurred.

In July 2011, the Treasury and Fed developed procedures to prioritize government payments in the event the debt limit was not increased in time. According to an FOMC transcript from that time, principal and interest on Treasury securities would continue to be made on time and other payments could have been delayed. Principal would have been paid by rolling maturing issues into new securities. To ensure the timely payment of interest, the Treasury would have held back other payments in order to accumulate sufficient cash balances to ensure sufficient cash on hand.

In 2013, FOMC transcripts described a similar procedure to prioritize payments on Treasury securities.

The Impact of Fiscal Policy Beyond the Near-Term

Alec Phillips

- 1 ^ Although the Budget Act of 1974 clearly allows revisions to the resolution, the Senate Parliamentarian has imposed some restrictions on the circumstances under which revisions can be made.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.