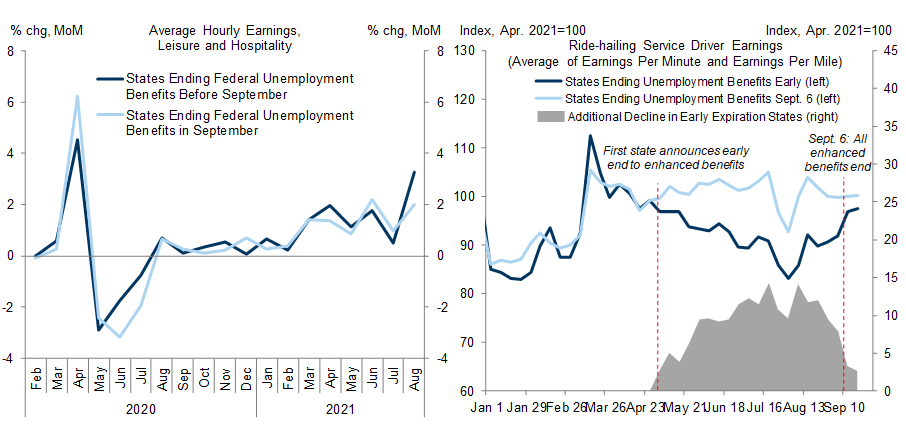

The two most important questions for the 2022 inflation outlook are whether global supply chains will recover enough for goods prices to normalize and whether wage growth will stop accelerating now that enhanced unemployment benefits have expired. We construct a scenario analysis for 2022 inflation based on alternative assumptions about these two key issues.

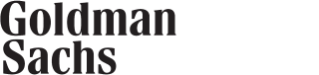

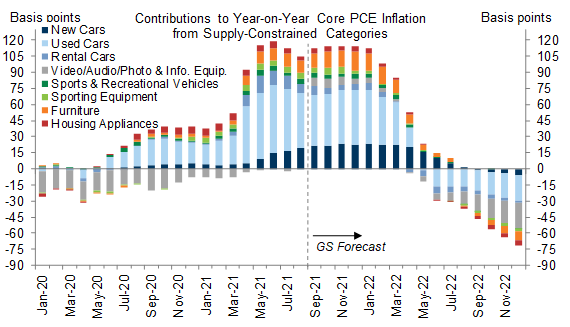

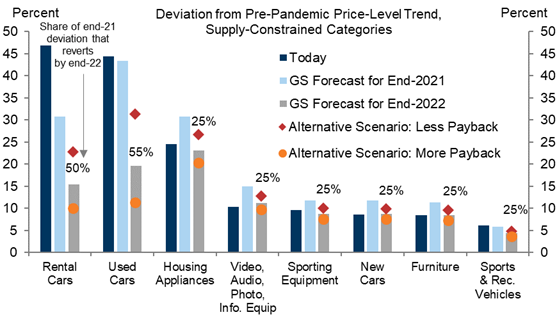

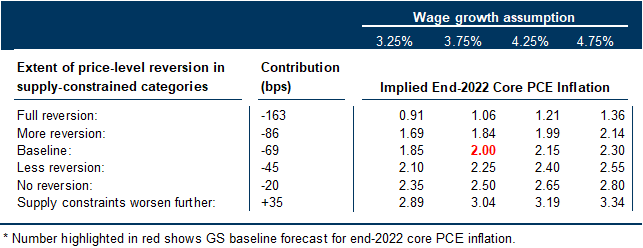

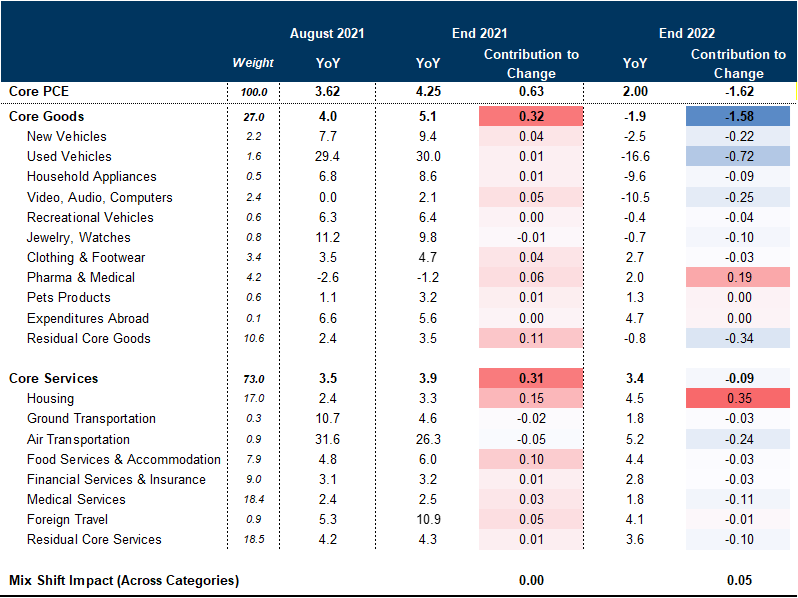

We expect ongoing supply chain disruptions to raise durable goods prices further above the pre-pandemic trend through end-2021, pushing core PCE inflation to 4.25% by December. But we expect the resolution of supply problems in 2022 to reverse about 30% of that deviation above trend on average by end-2022, worth a 185bp decline in the contribution to year-on-year core PCE inflation. We assume that wage growth for low-paid jobs will moderate, but labor market tightening will keep overall wage growth steady at 3¾% next year. These assumptions generate our baseline forecast that core PCE inflation will fall to 2.0% at end-2022.

Our scenario analysis suggests that a wide range of inflation outcomes is plausible. The extent of payback next year for unusually large durable goods price increases this year will have an especially large impact. Moderately more price level reversion in these categories coupled with somewhat softer wage growth could subtract another ¼pp from core PCE inflation at end-2022 relative to our baseline, while no reversion coupled with stronger wage growth could add ½pp or more, and further price increases in supply-constrained categories would add even more.

Supply Chain Disruptions, Wage Growth, and Inflation in 2022: A Scenario Analysis

David Mericle

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.