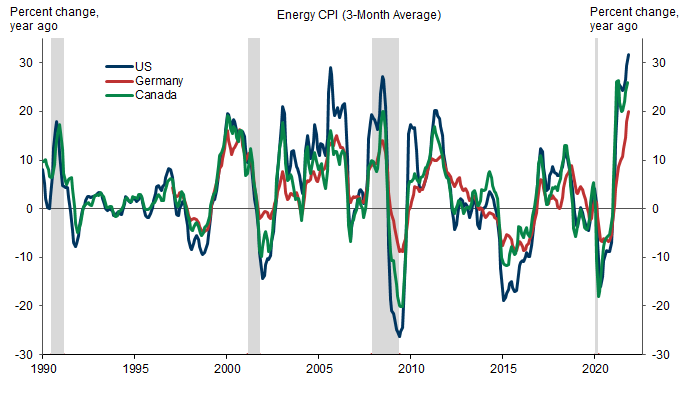

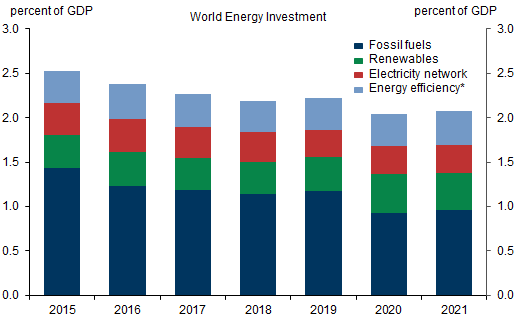

Surging energy prices have been an important driver of the jump in inflation. ECB President Lagarde pointed out recently that energy supply challenges related to climate change, alongside strong demand, have contributed to higher inflation. As energy investment keeps falling and policymakers have announced net zero targets, we estimate the inflation impact of this transition.

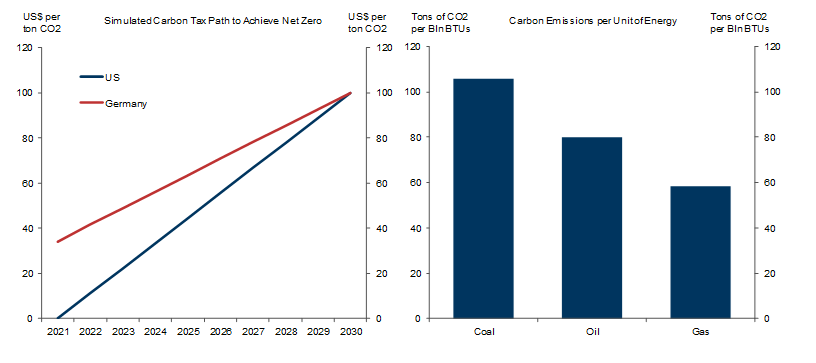

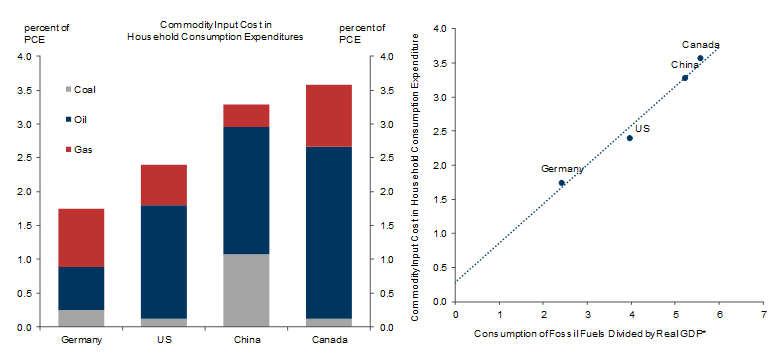

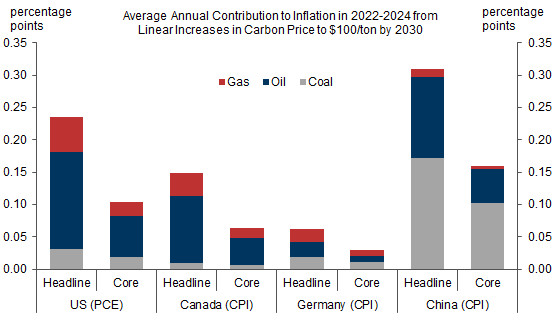

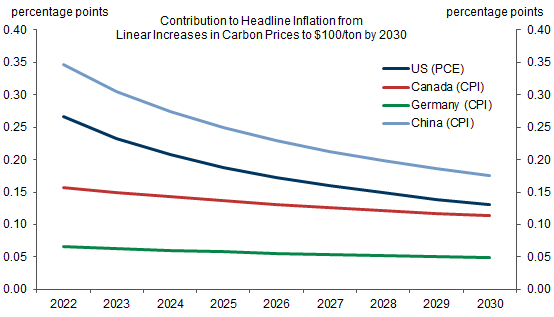

Based on expert estimates of what it will take to transition to carbon neutrality by 2050, we assume a carbon tax that rises linearly to $100 per ton—or roughly $1 per gallon of gasoline—by 2030. We then estimate the impact on consumer price inflation in four economies based on the carbon intensity of oil, natural gas, and coal and the contribution of these commodities to consumer prices.

We make three key findings. First, we estimate a boost from this transition path to the average US headline PCE inflation rate in the first three years of around 25bp annually. Second, the boost to core PCE inflation is smaller at 10bp. Third, the boost to headline inflation is larger in China at 30bp due to its greater reliance on coal. The boost is smaller in Canada (15bp) and especially Germany (just above 5bp) because both economies already have a carbon tax, Germany is relatively energy-efficient, and German gas prices are already very high.

The risks around our estimates are two-sided. Other mechanisms—including ESG-related market pressures to shun fossil fuel projects—could substitute for carbon pricing (which seems unlikely in the US for now), but at the cost of a somewhat larger inflation impact. The inflation boost may also be larger if the transition is delayed, if inflation expectations rise, or if fiscal stimulus boosts demand. The inflation boost may be smaller if higher policy rates cool the economy, or if producers and consumers rapidly switch to green alternatives, for instance in response to green subsidies.

Although the policy path is uncertain, we conclude that the eventual transition to net zero is likely to meaningfully boost inflation. This supports our view that inflation and nominal policy rates will settle above their pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, the estimated inflation effects appear modest relative to the importance and ambition of the net zero goal. A timely carbon pricing-driven transition thus appears manageable from an aggregate economic perspective.

Greenflation: The Impact of Net Zero on Inflation

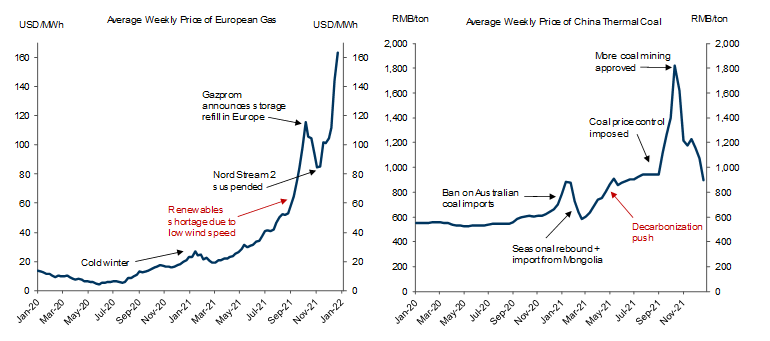

Exhibit 2: Decarbonization Efforts Have Contributed to Higher Prices of Gas in Europe and Coal in China

Modeling Net Zero

Exhibit 5: Commodity Inputs Costs Make Up More than 3% of Final Consumption Expenditures in Canada and China

Moderate Inflation Effects

Two-Sided Risks

Manageable Macro Costs

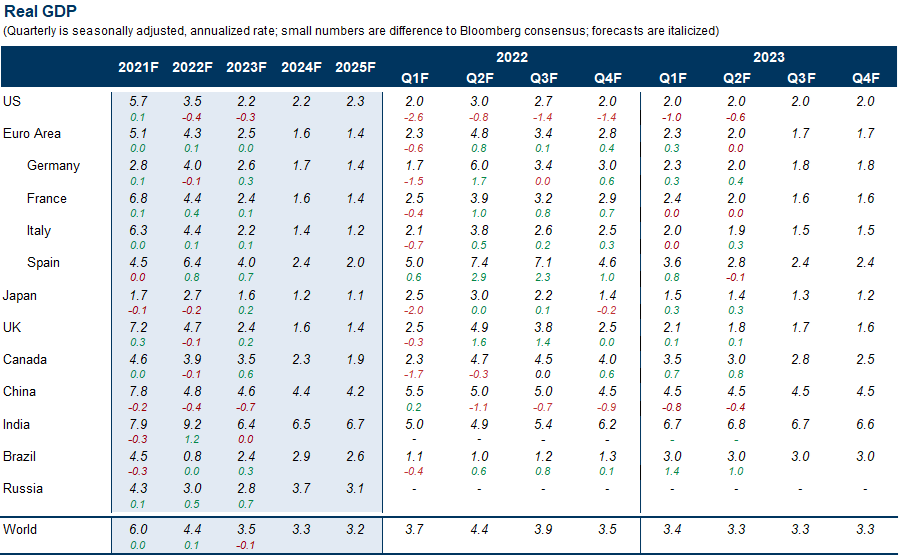

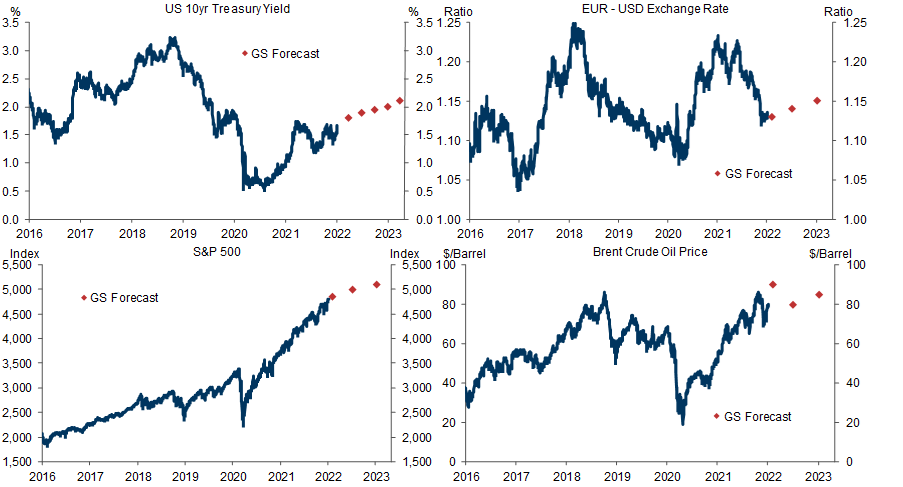

GS Global Macro Forecasts

Economic Forecasts

Market Forecasts

- 1 ^ For a discussion of carbon taxes as the most efficient solution, see Jeff Currie and Damien Courvalin, in “Investing in Climate Change 2.0”, Top of Mind, December 13, 2021.

- 2 ^ The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) is a network of central banks (including the Fed and the ECB) and financial supervisors that shares best practices for responding to climate change. See also Naohiko Baba, ‘Net Zero and Japan's Economy: Unpacking Standardized Simulation Results’, Japan Economics Analyst, 4 January 2022.

- 3 ^ Germany has two systems of effective carbon taxation: the European Emission Trading System and the new National Emission Trading System. We use the latter since the targeted heating and transport industries are more relevant for consumer prices.

- 4 ^ This pass through assumption is standard in the economics literature. It could reflect highly elastic long-run supply in competitive (commodity) markets.

- 5 ^ Our estimate of a 2½% share of oil, gas, and coal inputs in total US PCE expenditures is somewhat smaller than estimates for oil and gas of 2.85% in Hobijn (2008) and of 3.9% in Hale et al (2012) based on older input-output tables. See Bart Hobijn, “Commodity Price Movements and PCE Inflation.” FRB New York Current Issues in Economics and Finance 14-8, November 2008, and Galina Hale, Bart Hobijn, and Rachna Raina. 2012. “Commodity Prices and PCE Inflation”, Economic Letters, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 7 May 2012, and Ronnie Walker, “The Growth and Inflation Consequences of Higher Energy Prices”, US Daily, 19 October 2021.

- 6 ^ For more details on the “Net Zero 2050” and the “Delayed Transition” NGFS scenarios, see here.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.