History proves, some investors argue, that the inflation overshoot and overheated labor market have made a recession all but inevitable. Both inflation and wage growth have become much broader-based, and we agree that bringing them down will be very challenging. But such claims exaggerate the lessons of a handful of past episodes and understate the uniqueness of the current situation. We discuss what we know and don’t know about the inflation outlook, and what these nuances imply about the plausibility of the Fed taming inflation without a recession.

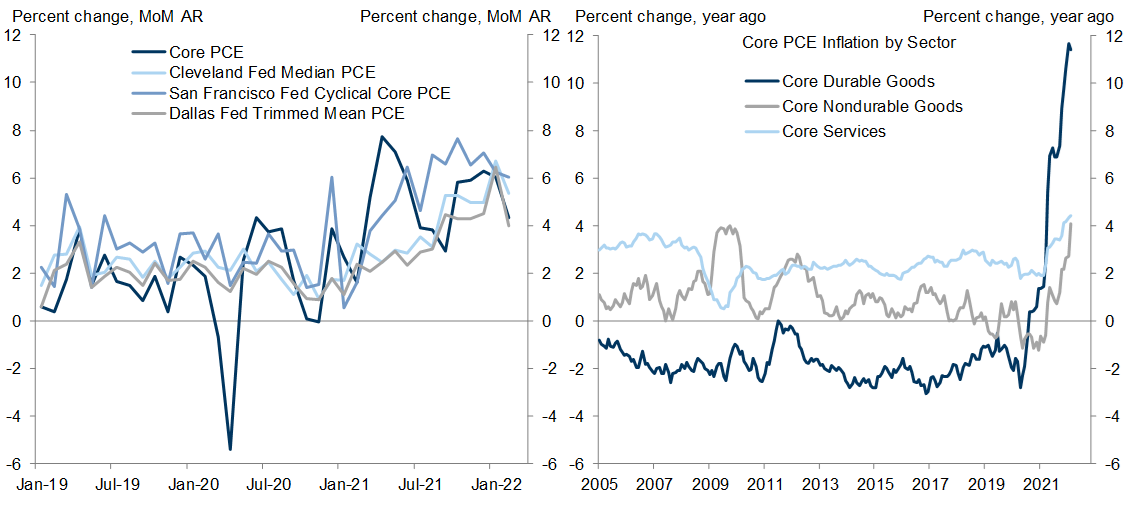

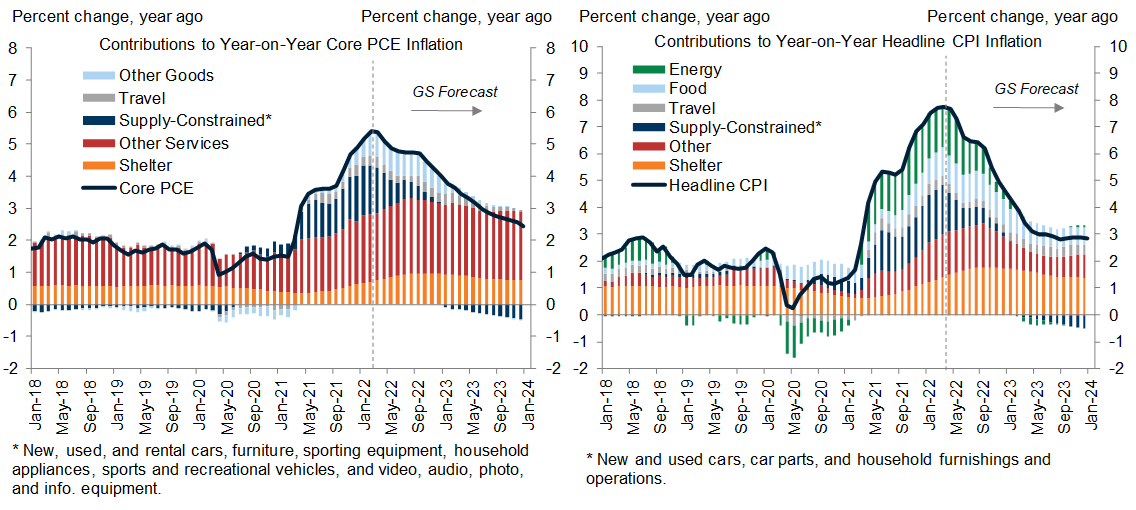

The most immediate unknown is how long supply-side problems will last. We are forecasting a large decline in core inflation this year and next driven largely by goods prices. The pandemic and the war in Ukraine pose obvious risks to this assumption, and more prolonged problems would make it harder to calm inflation. Ultimately though, for the inflation overshoot to be truly persistent, it will have to be driven mainly by high inflation expectations and wage growth.

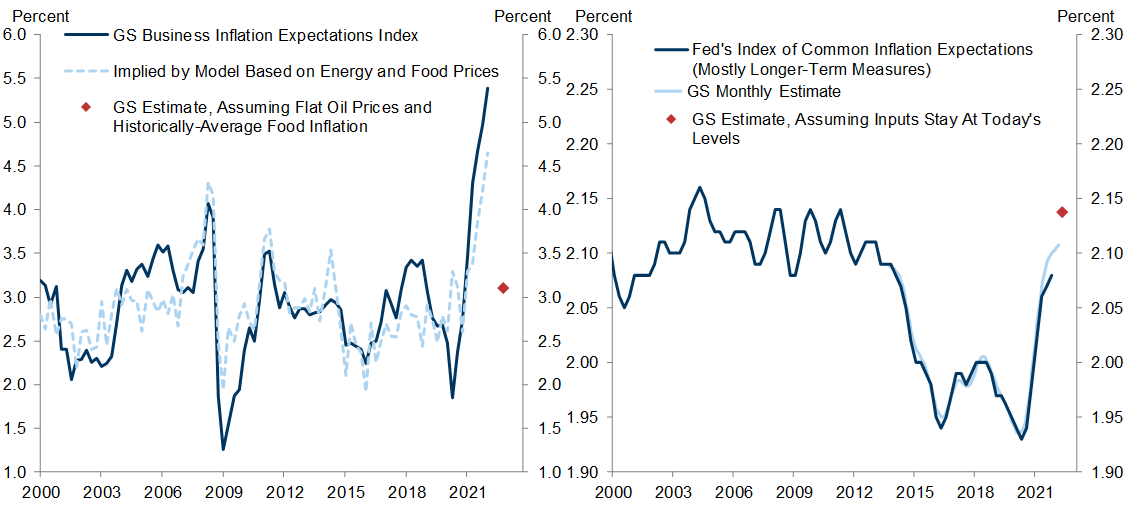

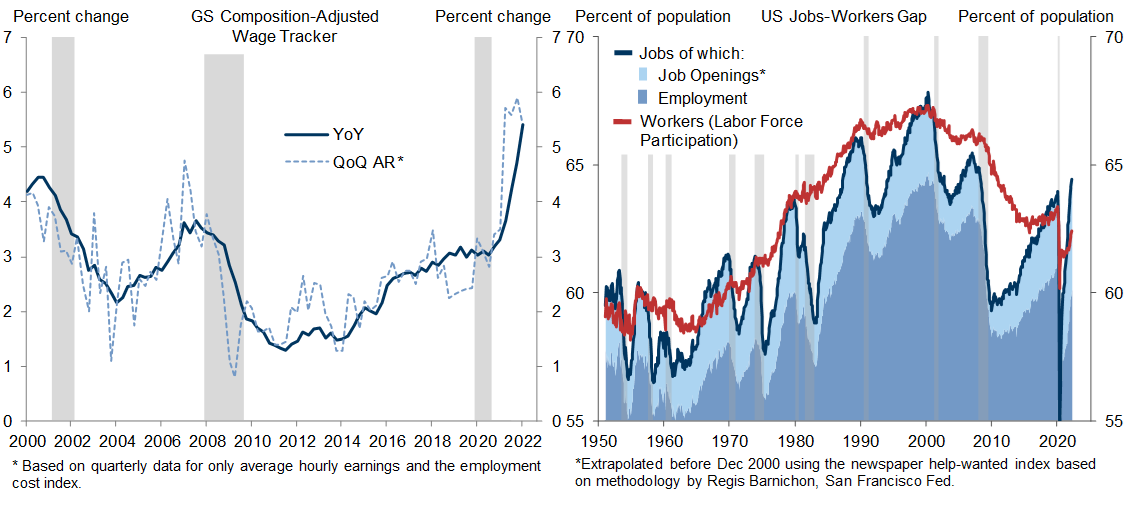

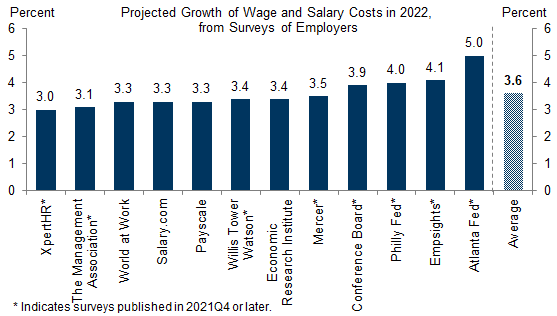

If the economy had definitively entered a wage-price spiral with inflation expectations and wage growth firmly entrenched well above target-consistent levels, then a recession might be the only solution. But reality is more complex and presents a mix of both concerning and reassuring signals. Short-term inflation expectations are much too high, but much of this appears attributable to energy price spikes, and long-term expectations remain well anchored. Wage growth has also run much too hot and the labor market is clearly imbalanced, but temporary factors have also contributed, and surveys show that companies expect to raise wages more slowly this year.

These nuances make it hard to fit the current situation into a single historical box. Comparisons with the soft landing in the mid-1990s, say, are too reassuring because reversing overheating is harder than just preventing it. But inflation expectations are not sufficiently unanchored to justify comparisons with the 1970s either. We see traces of both postwar inflation surges driven by supply-demand imbalances that faded and the wage-price spiral of the late 1960s. Historical comparison therefore offers reason for both comfort and concern, but not a definitive conclusion.

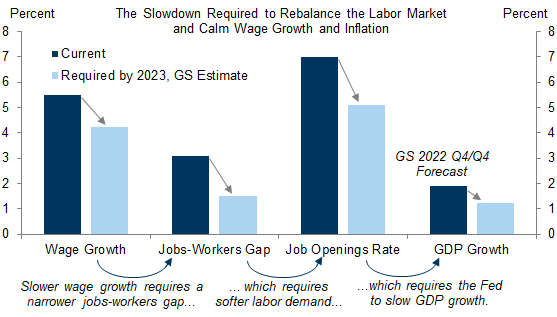

We recently introduced a framework for analyzing whether the Fed can tame inflation without a recession in a series of four steps. We first ask how much wage growth needs to slow, then how much the jobs-workers gap needs to shrink to achieve that, then how much of a decline in job openings that would take assuming some rebound in labor supply, and finally how much that requires GDP growth to slow. Our answer is that we do not need a recession but probably do need growth to slow to a somewhat below-potential pace, a path that raises recession risk.

A Recession Is Not Inevitable

David Mericle

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.