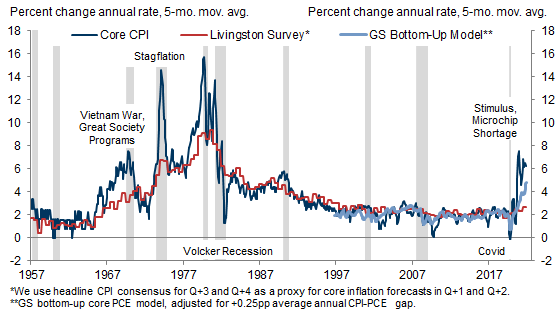

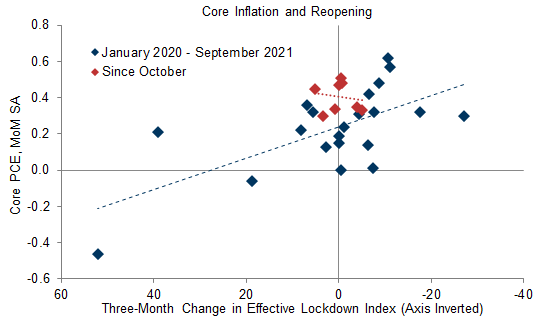

Core CPI inflation has continued to surprise to the upside on net, with core CPI beats in each of the last two months and four of the last six reports. Additionally, the magnitude of these upside surprises is beginning to rival those of the 1960s overheating and 1970s stagflation. This raises the question of whether forecasters have simply been surprised by a strikingly long chain of unforeseen supply-side problems, or whether consensus inflation forecasts are missing something important.

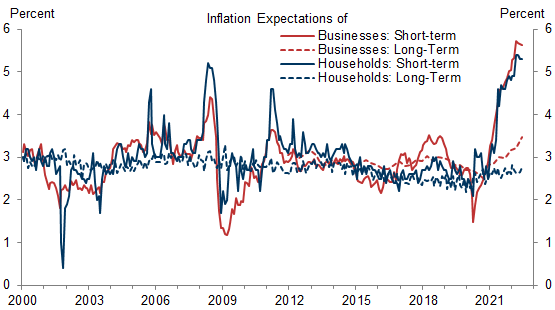

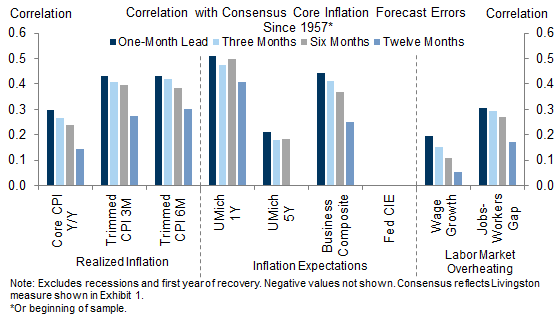

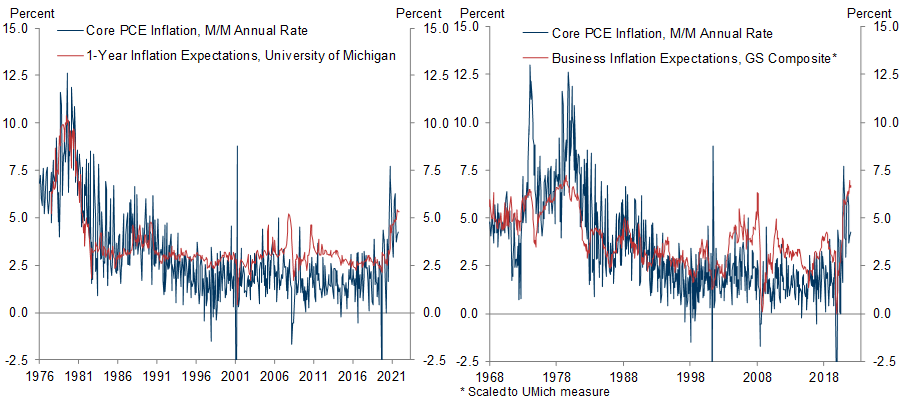

Analyzing consensus inflation surprises over the last 75 years using the Livingston survey, we find that forecasters on average failed to incorporate the signal from short-term consumer inflation expectations, business inflation expectations, and the jobs-workers gap. This suggests that today’s models might also be underestimating the significance of these factors.

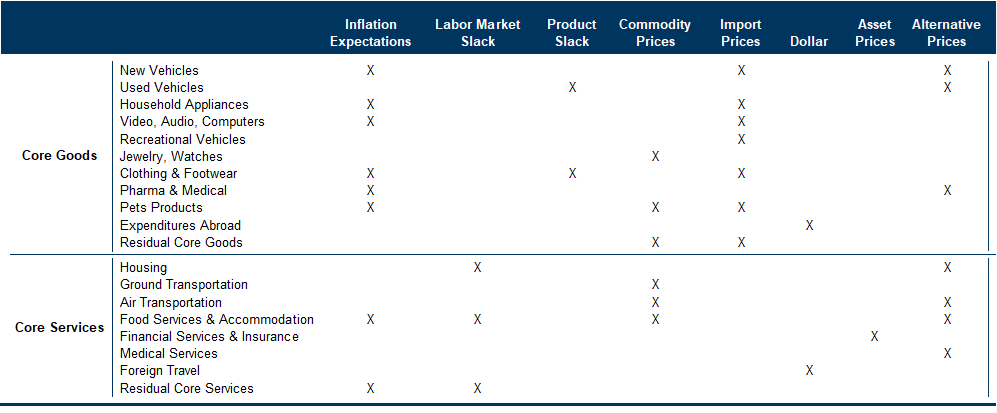

We test these variables in our component-level inflation models, finding significance in nearly half of the categories. Our models also continue to include (1) measures of labor and product market slack; (2) indicators related to pass-through from commodity, import, and asset prices; and (3) alternative price indices available from non-government sources.

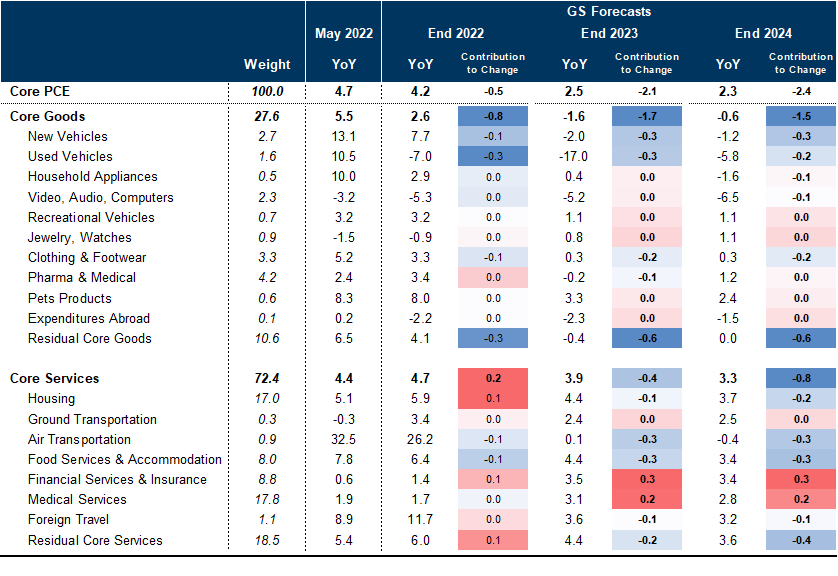

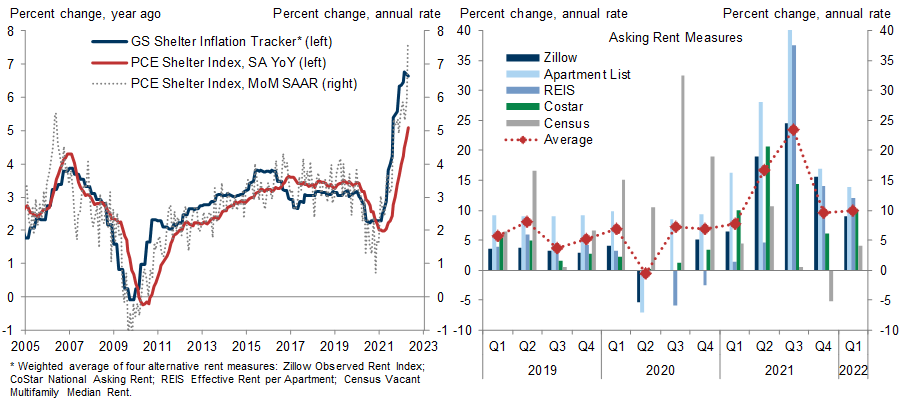

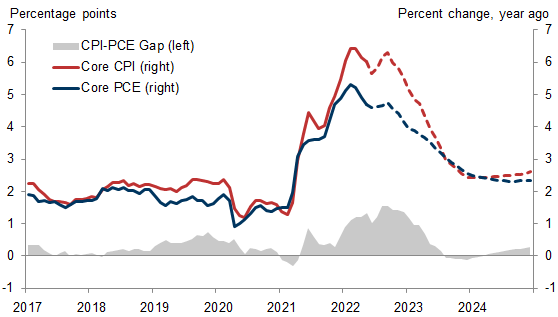

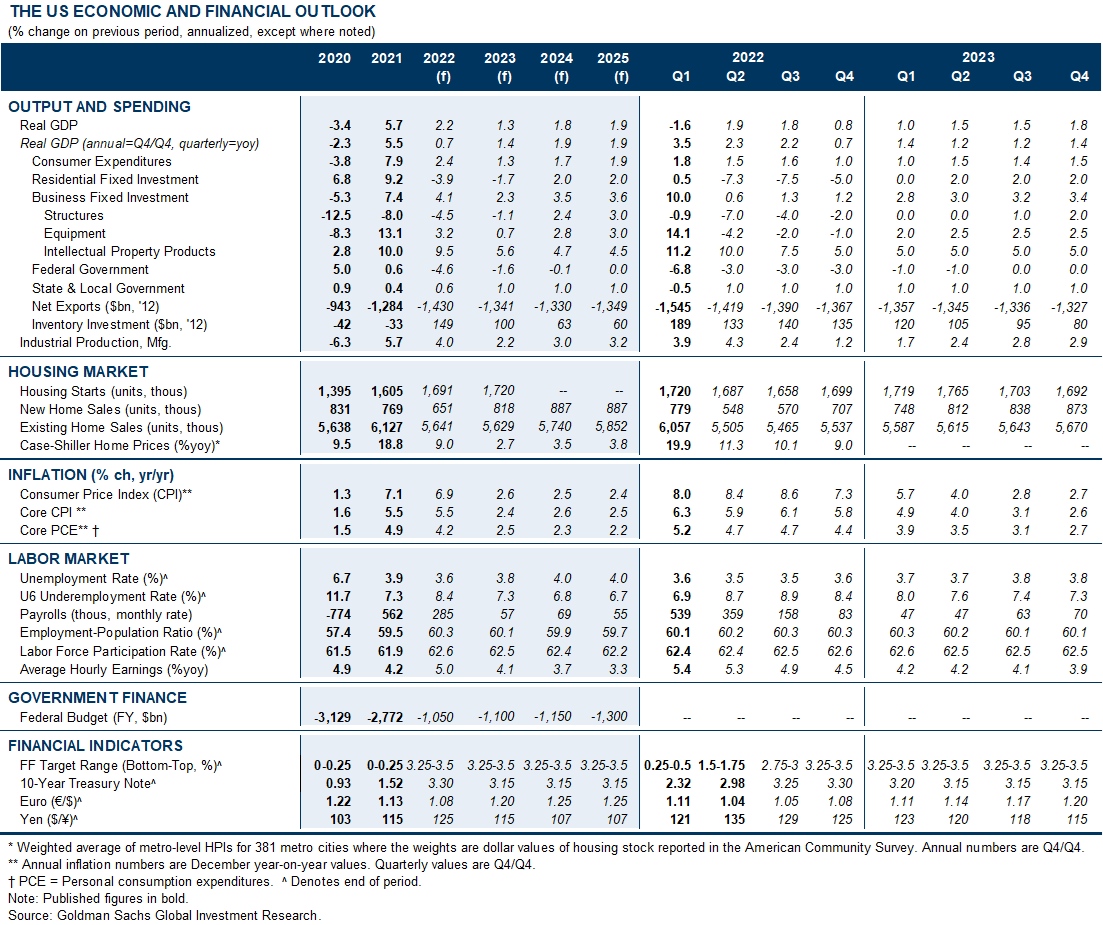

We are raising our year-end core PCE inflation forecasts for 2022-2024 to 4.2%, 2.5%, and 2.3% respectively (vs. 4.0%, 2.3%, and 2.2% previously, and compared to 4.7% in May). This reflects additional upward pressure in cyclical services categories like household maintenance, personal care, and food services and accommodation. However, we are leaving our 2023 and 2024 shelter inflation forecasts unchanged despite the May price spike because alternative rent measures are already slowing and the May geographic cross-section is consistent with a one-off boost from the reversal of pandemic discounts.

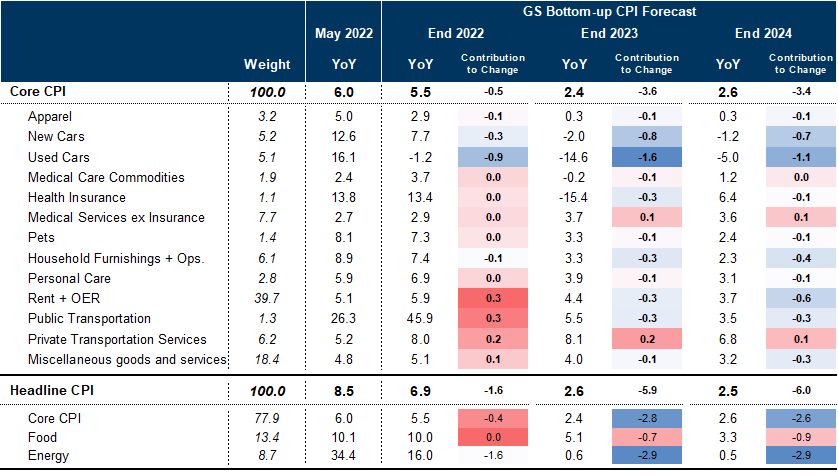

We also introduce a new bottom-up core CPI model, which we will update alongside our PCE forecasts in our Monthly Inflation Monitor. Unlike the PCE measure, we expect year-on-year core CPI inflation to reaccelerate in late summer—from 6.0% in May to 6.3% in September—before falling to 5.5% at year-end, 2.4% in December 2023, and 2.6% in December 2024 (vs. 5.1%, 2.6%, and 2.6% previously).

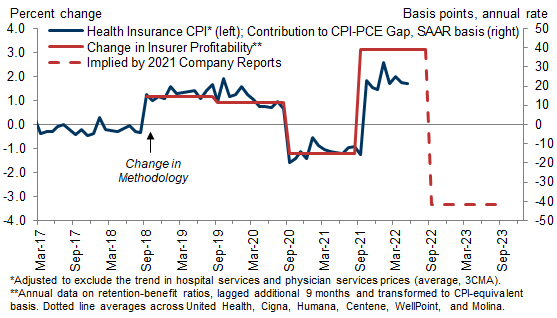

As we highlighted last fall, the CPI-PCE gap will be much larger than usual this year because of the larger weights on the shelter and durable goods categories and differences in the measurement of health care inflation. However, we continue to expect the gap to narrow beyond this fall, when durable goods prices should start to normalize and the CPI’s health insurance category should transition from very strong to very weak as new annual source data are incorporated.

Back to the Future: Forecasting Inflation When Expectations Are Evolving

What to Expect When You're Expecting High Inflation

Updating Our Bottom-Up Core PCE Model

A Hot Summer for Core Inflation and the CPI-PCE Gap

Spencer Hill

Ronnie Walker

Manuel Abecasis

- 1 ^ The survey collects data only on headline inflation, and respondents generally incorporate the recent path of oil and food prices into their forecasts of near-term inflation. Accordingly, we construct a proxy for core CPI consensus using the headline CPI forecast for quarters Q+3 and Q+4—for which the recent path of commodity prices is often a secondary or minor factor from a forecasting perspective. We find broadly similar results when replicating our analysis using headline CPI consensus, except generally lower correlations with realized inflation.

- 2 ^ We also cannot rule out the risk that elevated realized inflation leads short-and long-term inflation expectations even higher, particularly if the labor market continues to overheat.

- 3 ^ The lag structure for dependent variables differs by category based on statistical and economic significance.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.