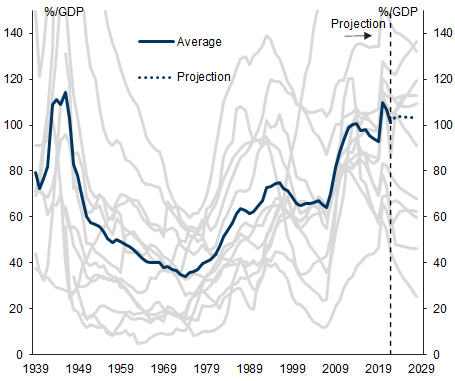

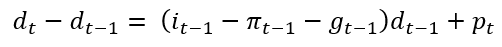

With public debt-to-GDP levels in developed markets at multi-decade highs, the recent rise in inflation and policy rates is refocusing attention on debt dynamics as interest costs increase and fiscal policy adjusts following the pandemic.

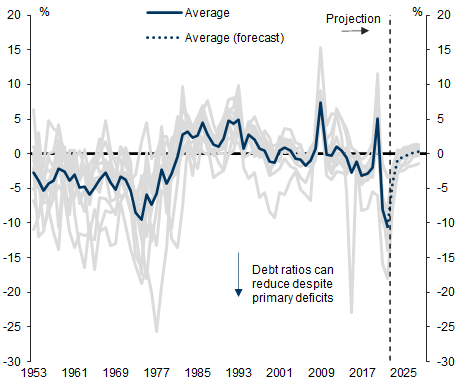

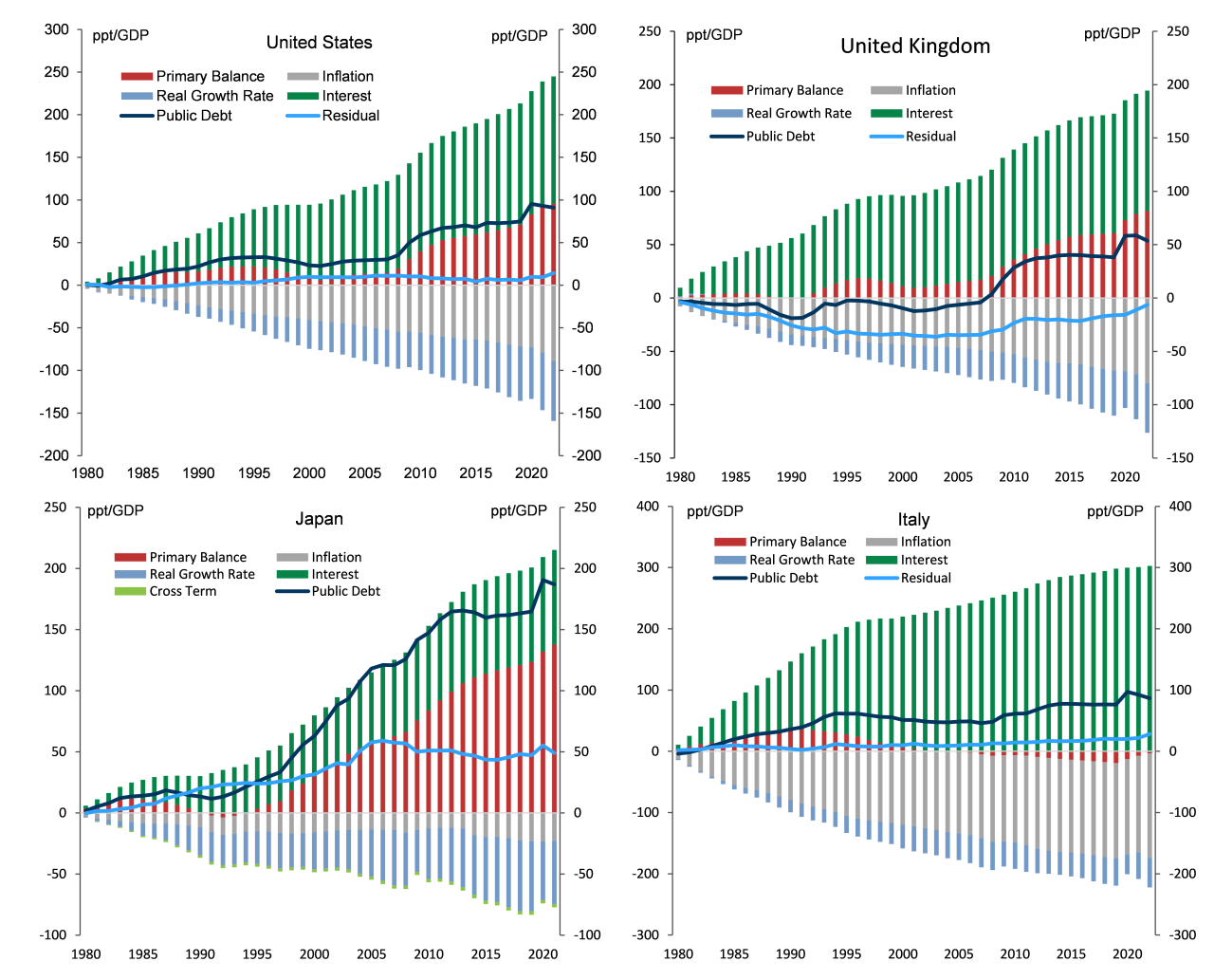

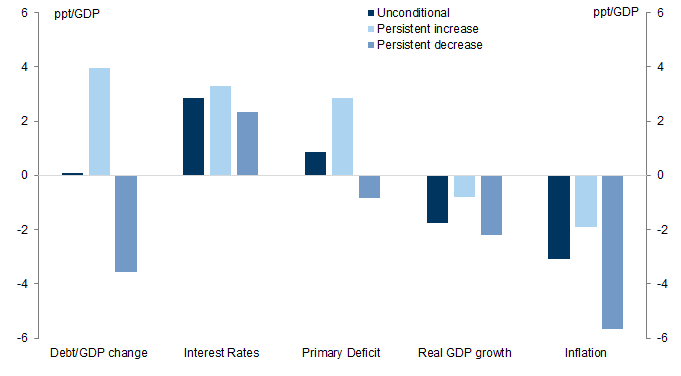

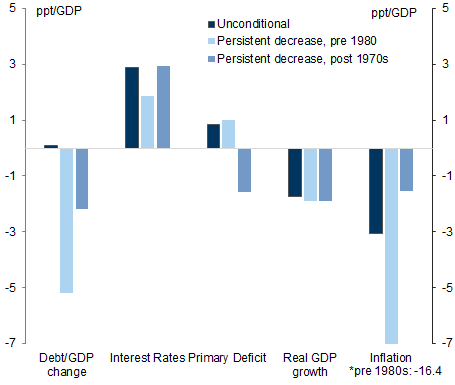

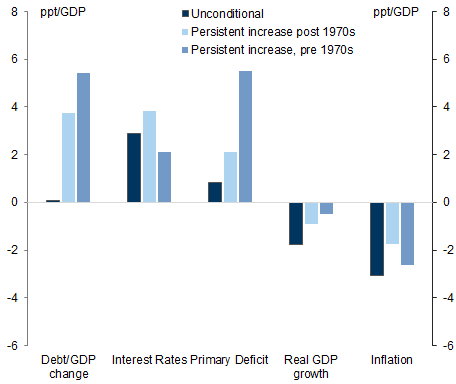

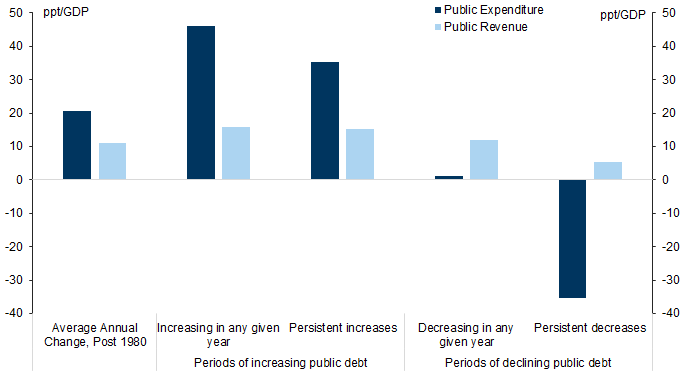

Using a debt accounting exercise, we show that periods of sustained debt reduction are typically driven by strong primary balances and above-average growth. Following 1980, inflation has played little role in debt reductions.

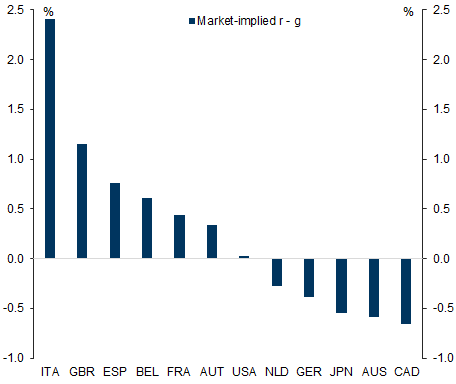

Current fiscal projections and current market interest rates on average do not point to declines in debt-to-GDP ratios across DMs. We estimate that market implied r - g, the difference between real interest rates and growth rates, is now positive for many countries.

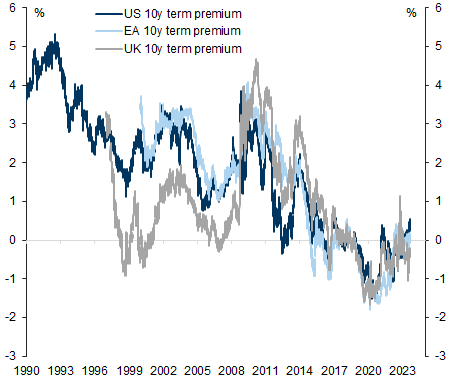

Japan provides an example of high debt peaceably coexisting with low interest rates. However, given current high inflation, wider deficits, and rising interest costs, we think it unlikely that we return to the era of structurally low interest rates in the US, UK or Europe. As a result, we see the risks to term premia skewed higher as fiscal risks simmer.

Exhibit 5: Debt reductions post-1980 primarily driven by stronger primary balances

Exhibit 6: Debt increases post-1980 also driven by primary deficits

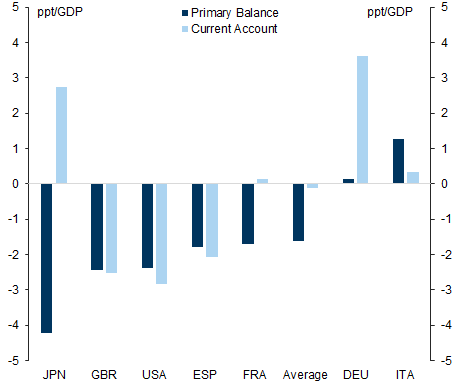

Exhibit 8: Market-implied r - g highest in European economies

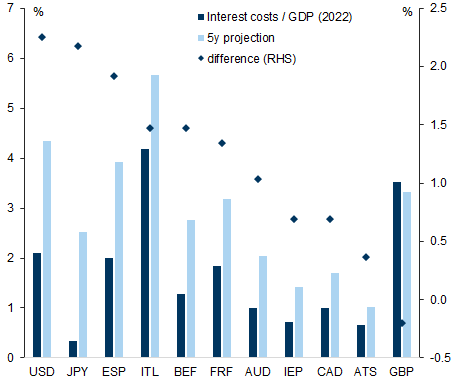

Exhibit 9: US will see largest rise in interest costs

Appendix

National sources and OECD collected via Haver Analytics

IMF data from Mauro, P., Romeu, R., Binder, A., & Zaman, A. (2016, December 31). A modern history of fiscal prudence and profligacy. IMF. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/A-Modern-History-of-Fiscal-Prudence-and-Profligacy-40222

International Monetary Fund. (2015). Public Finances in Modern History [Dataset]. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/FPP

Reinhard Rogoff Dataset from Reinhart, C., & Rogoff, K. (2011). From financial crash to debt crisis. The American Economic Review, 101(5), 1676–1706. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.5.1676

- 1 ^ Debt dynamics are also affected by stock adjustments, ranging from accounting classification to nominal debt restructuring; however, we set these aside in our analysis, and allow any such changes to be captured in the residual term.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.