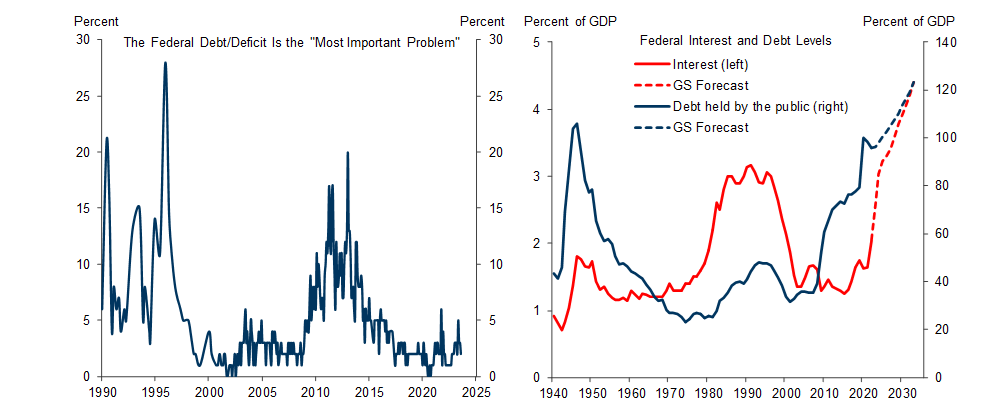

A sharp rise in long-term interest rates combined with widening deficits and heightened fiscal discord in Congress have renewed questions about the sustainability of rising government interest costs.

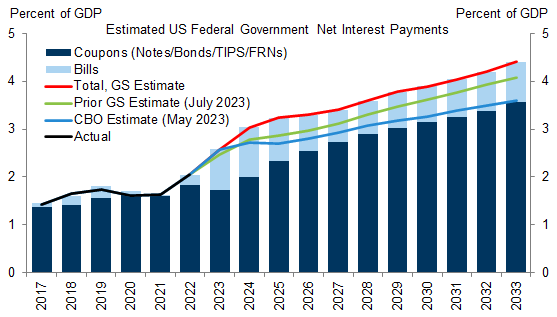

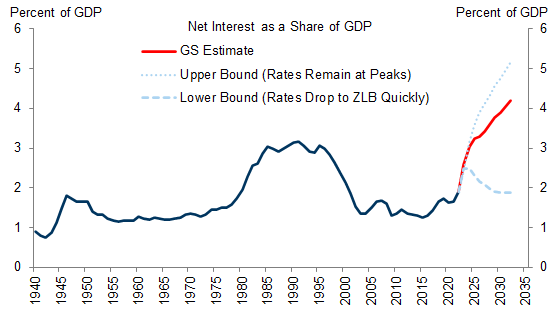

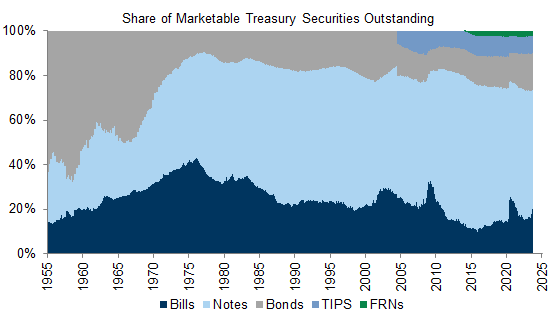

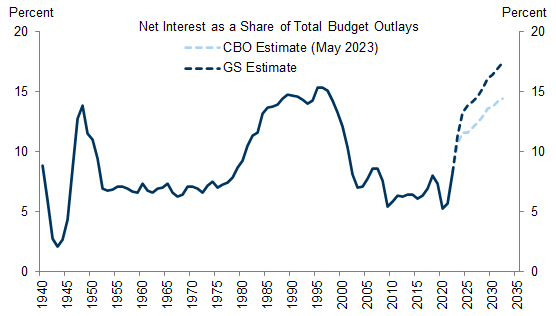

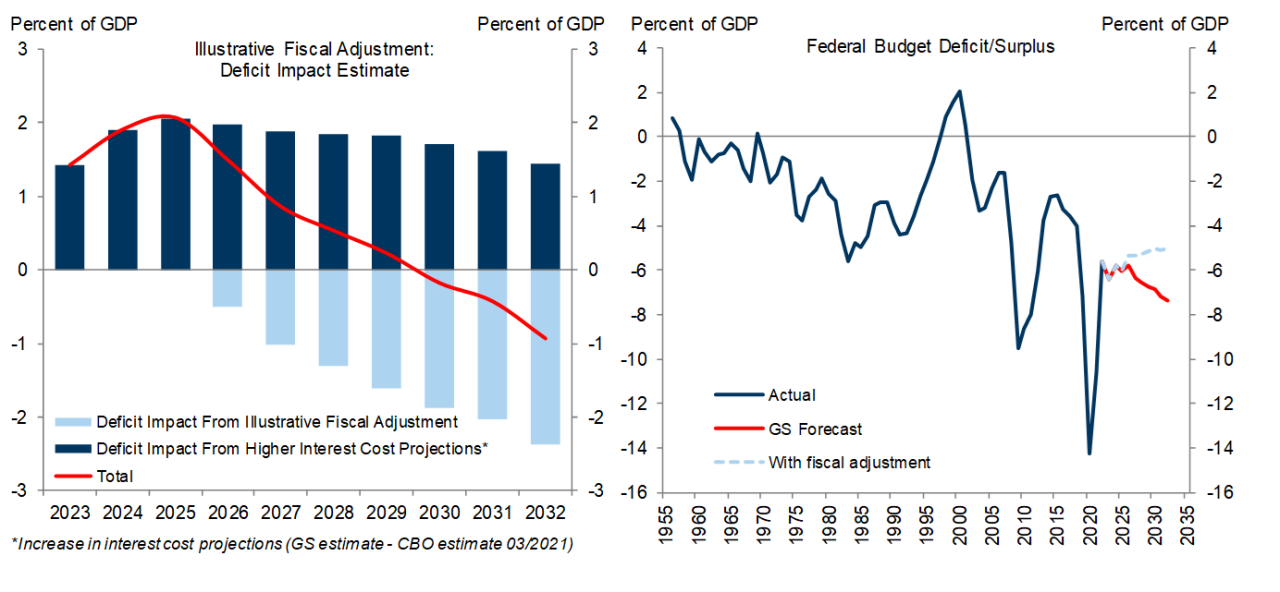

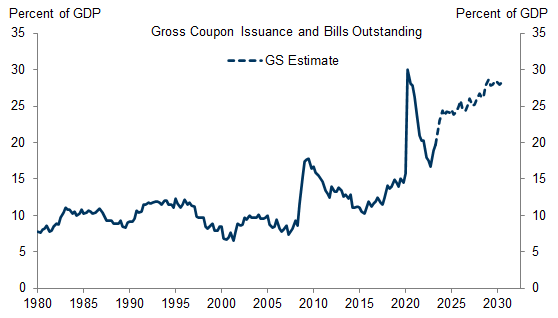

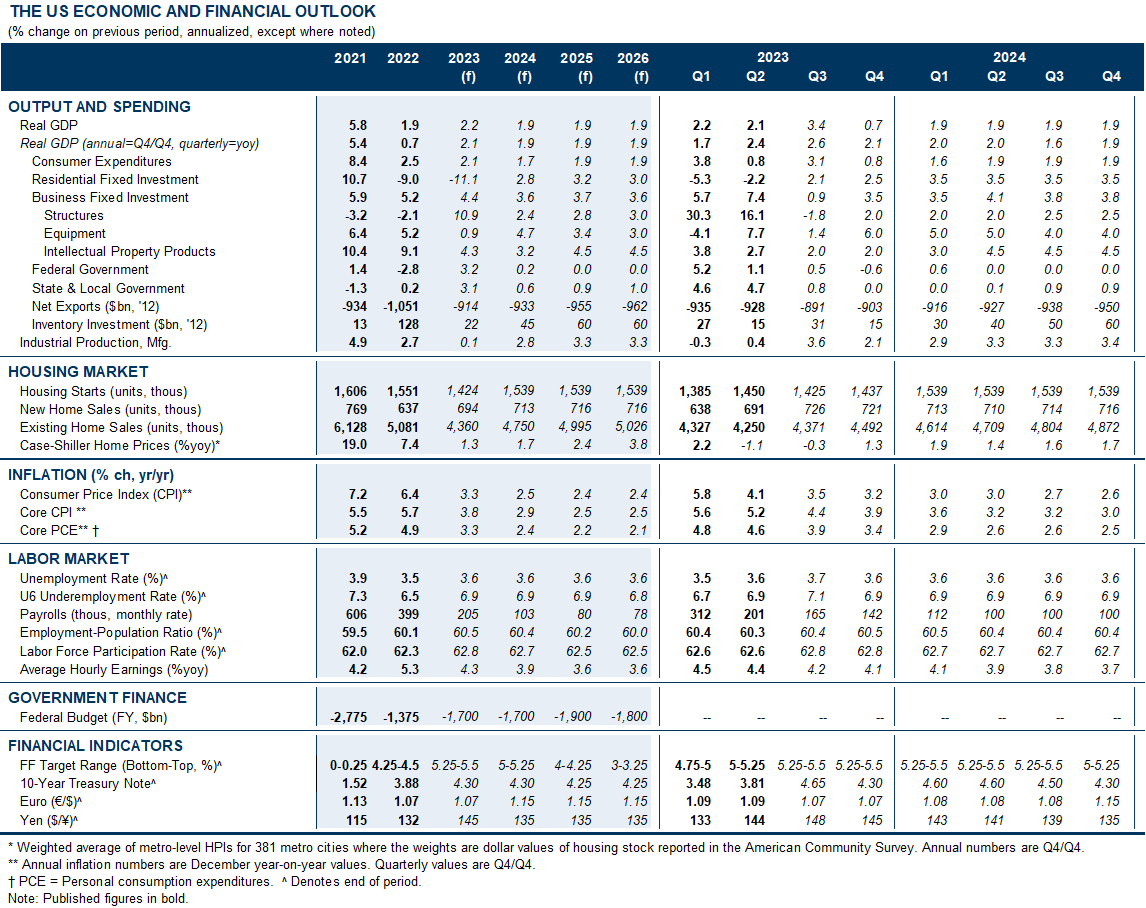

We project federal interest expense will rise from 2% of GDP in 2022 to 3% in 2024 and 4% by 2030, surpassing the early 1990s peak by 2025. On average over the next decade, higher interest expense is likely to add an additional 0.3% of GDP to the annual deficit compared to our July projections. In the near term, we have raised our deficit estimates for FY2024 by $50bn to $1.7tn (6.0% of GDP) and FY2025 by $100bn to $1.9tn (6.5% of GDP).

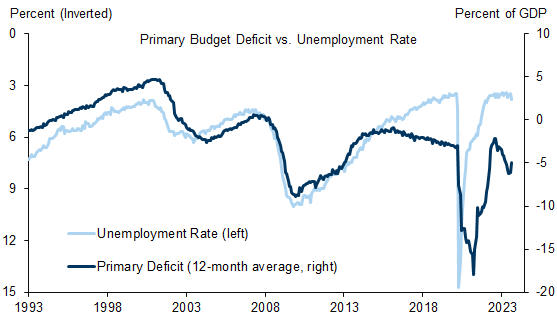

When interest expense rose sharply in the 1980s, fiscal policymakers reacted by shrinking the primary (ex-interest) deficit. The largest fiscal adjustment from that period, enacted in 1993, would be sufficient if enacted now to offset the additional interest expense we project (relative to 2021) after 5 years. However, this looks unlikely anytime soon given congressional gridlock, a lack of political attention to deficit reduction, and the upcoming 2024 election.

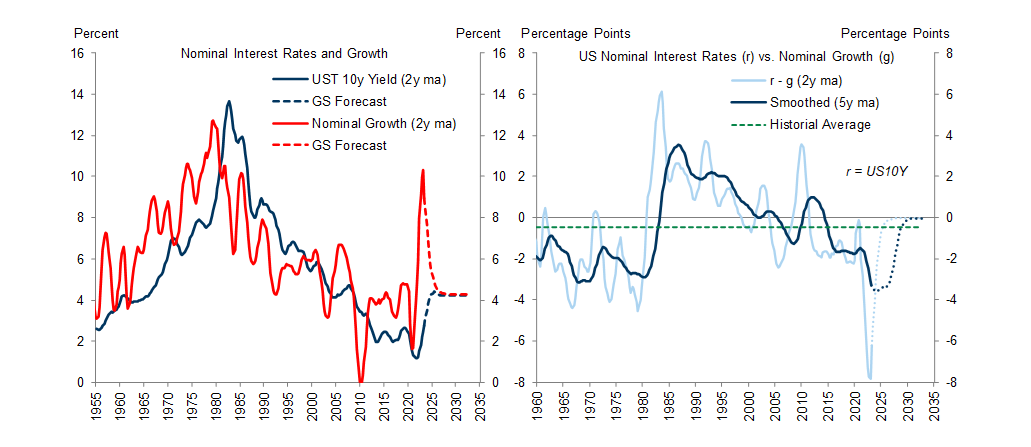

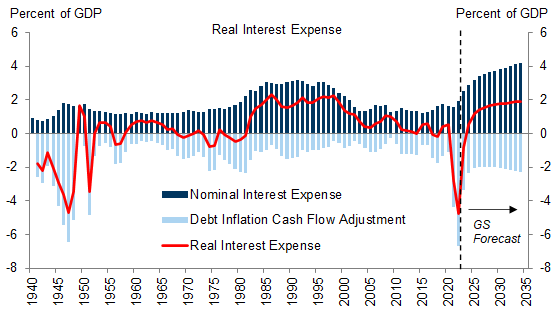

While higher interest expense will add to the deficit, the impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio should be much smaller. The average interest rate on federal debt is likely to remain at or below the rate of nominal GDP growth for the next decade, and this relationship is likely to be more benign than the historical average over the next five years. A larger debt stock but a lower interest rate-growth differential implies that real interest expense as a percent of GDP—the cost of stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio—will be comparable to the level in the late 1980s and 1990s.

Ultimately, the main challenge facing fiscal policy remains the large structural primary deficit, not interest expense. We estimate that debt as a share of GDP will rise from 96% to 123% over the next decade, driven primarily by a chronic primary deficit of around 3%. Although nominal GDP growth is likely to mostly offset the effect of higher interest costs on the debt-to-GDP ratio, the structural deficit will continue to add to public debt for the foreseeable future.

Interest Expense: A Bigger Impact on Deficits than Debt

Rising Interest Costs

Higher Interest Costs Could Eventually Lead to Fiscal Tightening

A Strong Nominal Growth Cushion

Exhibit 8: A Larger Debt Stock but a Lower r-g Implies That Real Interest Expense as a Percent of GDP—the Cost of Stabilizing the Debt-to-GDP Ratio—Will Be Comparable to the Level in the Late 1980s and 1990s

Tim Krupa

Alec Phillips

- 1 ^ For more details, see “Select Portfolio Metrics” of the Treasury Presentation to TBAC here.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.