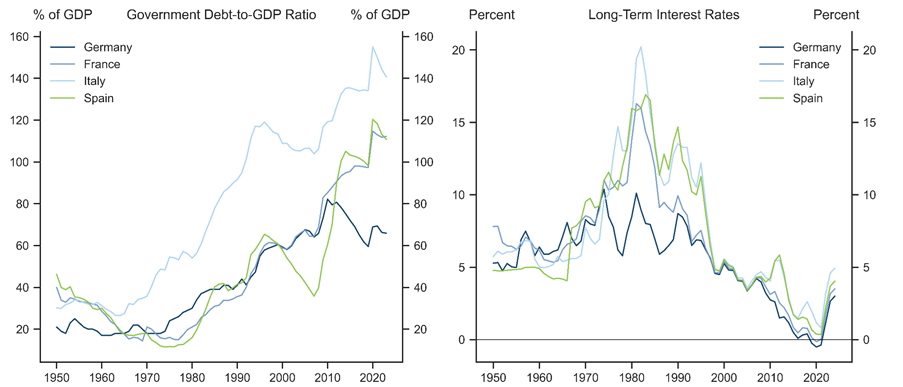

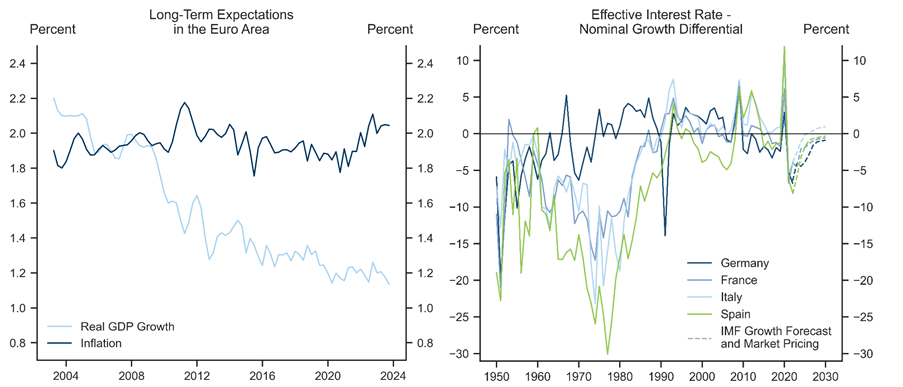

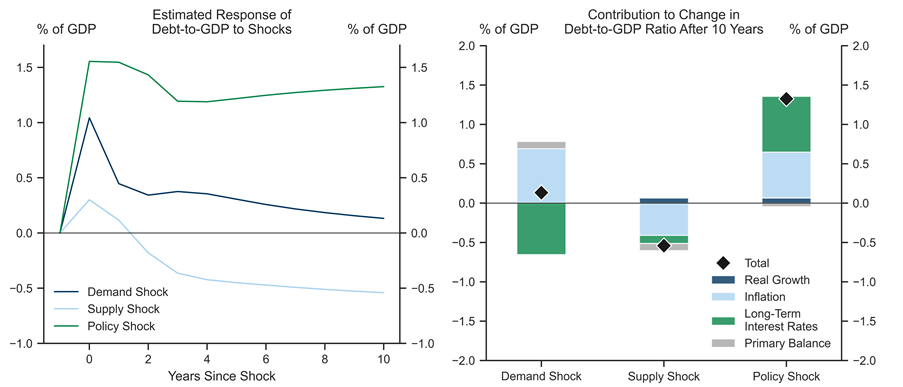

The increase in long-term interest rates has brought the longer-term outlook for debt sustainability back into focus. The limited changes in long-term real growth and inflation expectations imply that the differential between the effective interest rate on debt and nominal growth (i-g) is set to return close to its late-1990s average. The ratio of primary (ex interest) balances would therefore have to improve by 1pp to 3pp of GDP to prevent an increase in the debt ratio—the simplest criterion for debt sustainability.

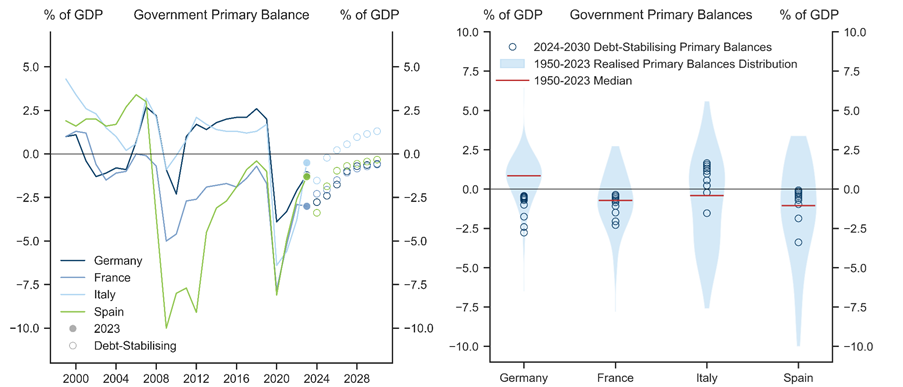

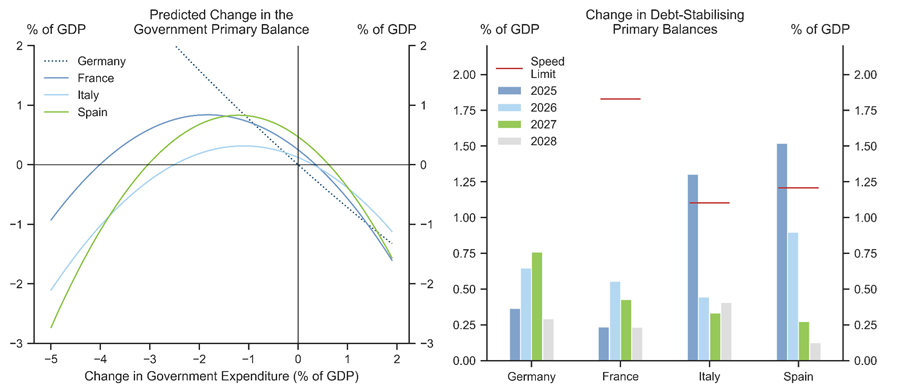

Our assessment suggests that the required consolidation paths look largely attainable. First, primary balances will need to reach terminal levels which remain well within the historical range for most countries, albeit at the upper end for Italy. Second, the pace at which primary balances will have to improve falls short of our estimates of so-called “speed limits” to consolidation. Lastly, we see reasons to look for consolidation efforts to be relatively less detrimental to growth than in the past.

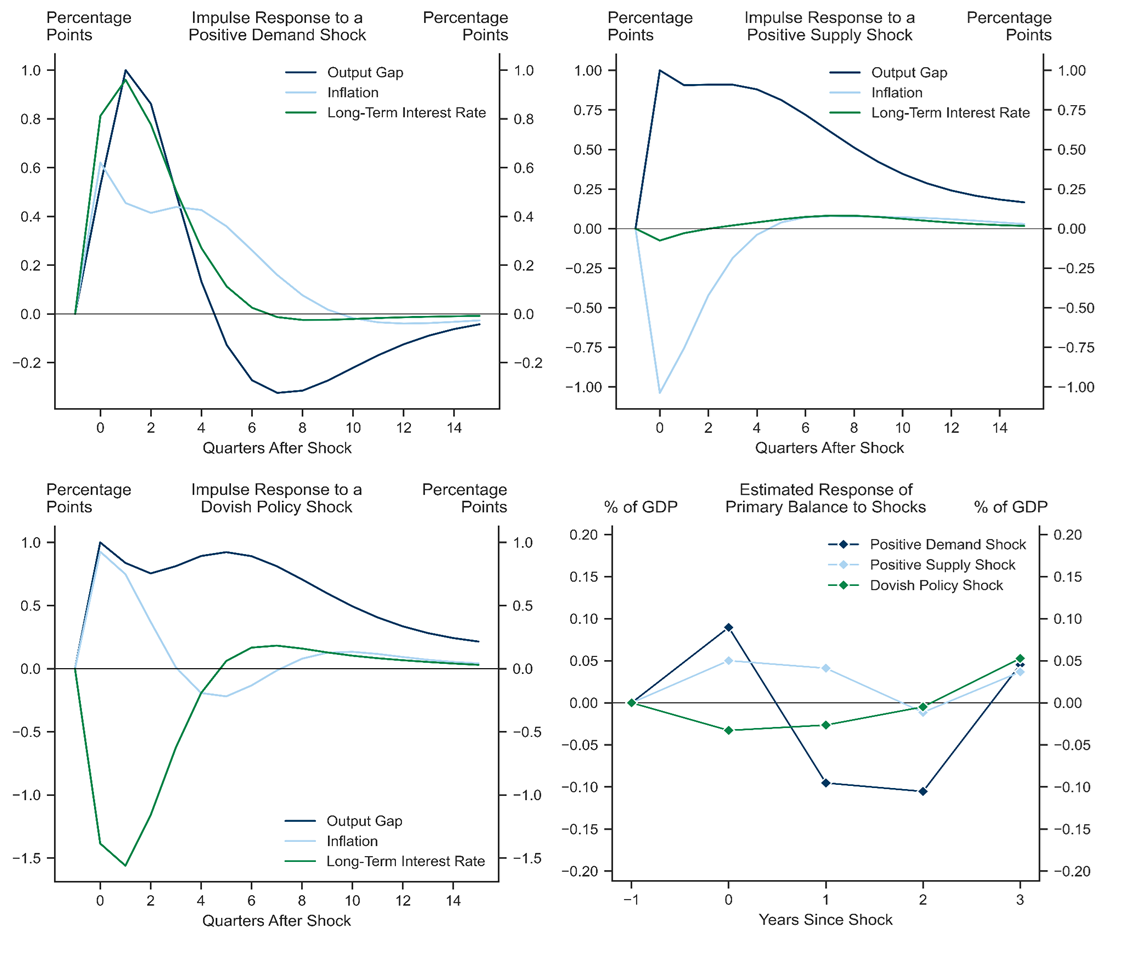

Our central case is, however, exposed to risks, and the past few years have shown that the sources of shocks hitting the economy can be very relevant to debt dynamics. The energy crisis, for instance, has been a significant drag on growth and triggered a forceful policy response, but is likely to leave the debt ratio broadly unchanged because of the diluting effects from inflation. Our analysis suggests that debt trajectories in the Euro area are most exposed to an unwarranted tightening in interest rates, where interest rates rise despite weaker growth and inflation.

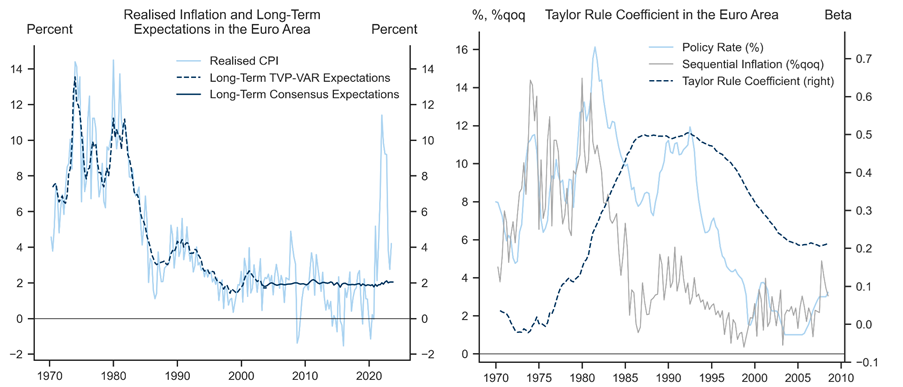

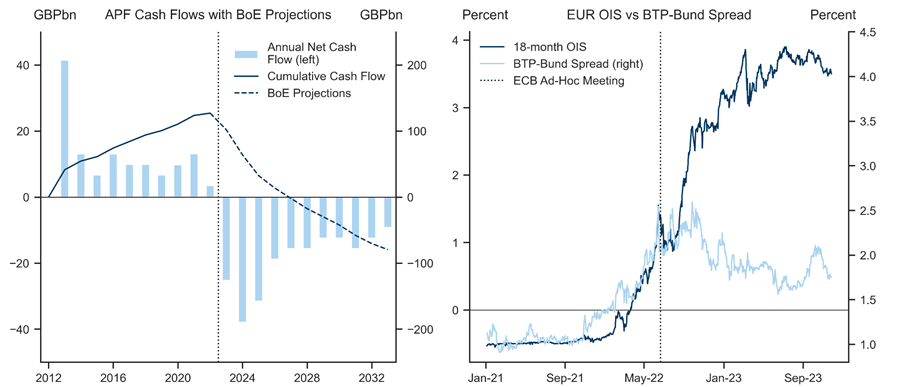

While central banks have historically helped achieve debt sustainability by, for instance, maintaining deeply negative real rates in the post-war era, the return of inflation in the Euro area has exposed two different trade-offs. A forceful response of policy rates to inflation anchors inflation expectations and helps contain the inflation premia embedded in government bonds, all else equal. And while the use of the central bank’s balance sheet is never a “free lunch,” the perceived credibility of the ECB’s commitment to guard against non-fundamental sovereign stress has so far proven to be relatively cheap and effective.

Euro Area—Debt Sustainability and Higher Rates

Sizing The Challenge

Exhibit 2: Interest Rate – Growth Differential Deterioration

Exhibit 3: Primary Balances Back Within their Historical Range

Exhibit 4: Consolidation Pace Unlikely to Bind

Sources of Risk

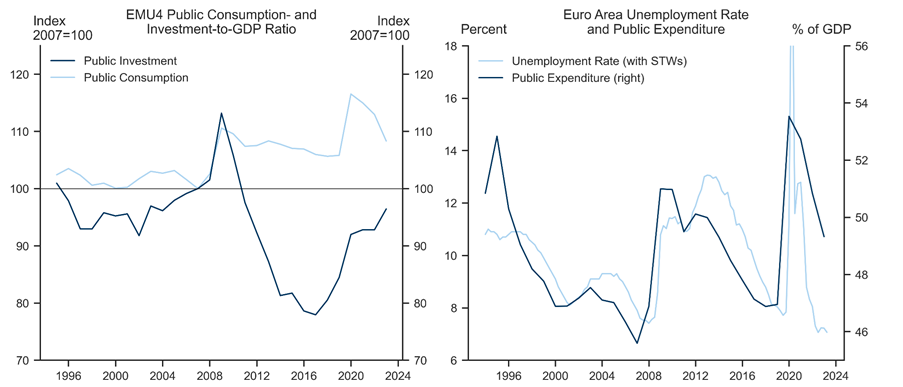

Exhibit 6: Fiscal Environment and Macro Shocks

The Central Bank’s Role

Exhibit 8: Policy Rates and Debt Sustainability

Exhibit 9: Balance Sheet Policy a "Cheap Lunch" Thus Far

- 1 ^ We regress the change in primary balances on the change in expenditure and the squared change in expenditure. The coefficient on the squared change in expenditure is negative and statistically significant for France, Italy, and Spain. This coefficient in Germany is not statistically different from zero.

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.