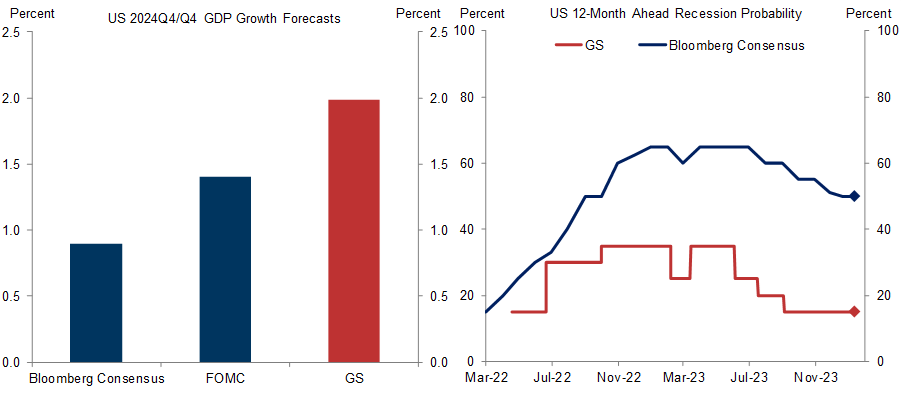

We expect much stronger GDP growth in 2024 than consensus and see a much lower risk of recession. What are other forecasters worried about that we aren’t? This Analyst looks at 10 risks for 2024 that are often highlighted by other forecasters and explains why we worry less.

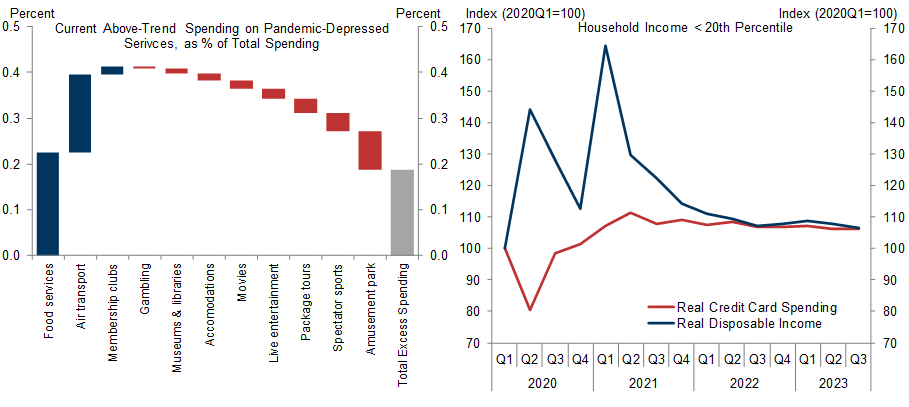

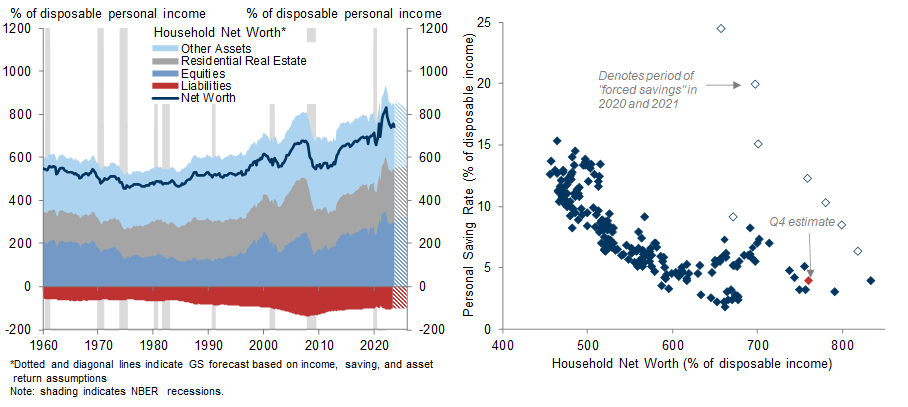

Risk 1: A consumer slowdown looks unlikely because real income should grow about 3% and household balance sheets are strong. Current spending patterns do not appear unsustainable and the saving rate does not look puzzlingly low at a time when household wealth is very high.

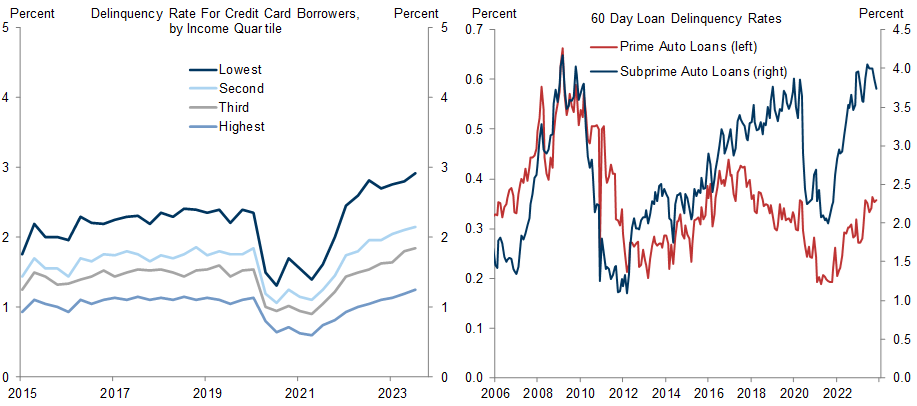

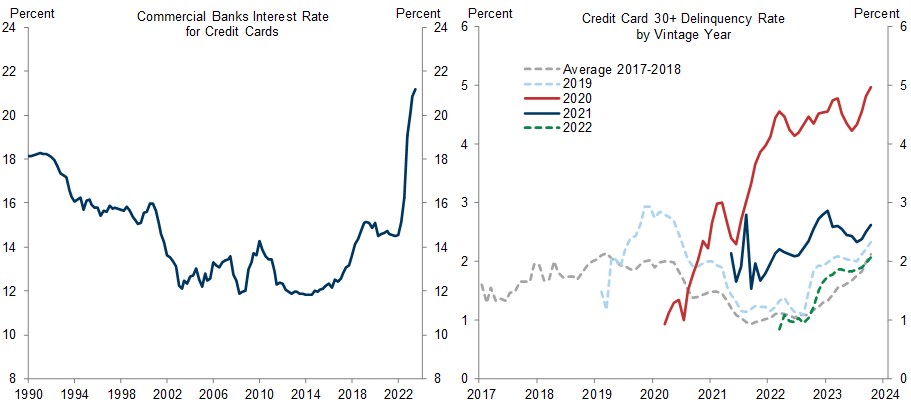

Risk 2: Rising consumer delinquency and default rates mostly reflect normalization from very low levels in recent years, higher interest rates, and riskier lending, not poor household finances.

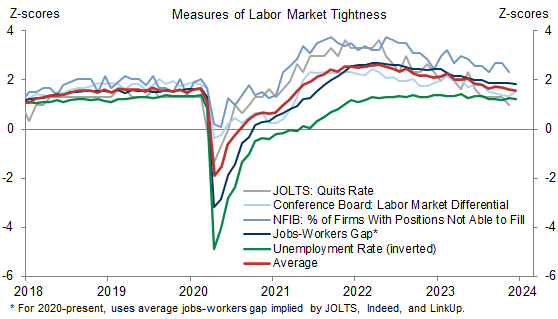

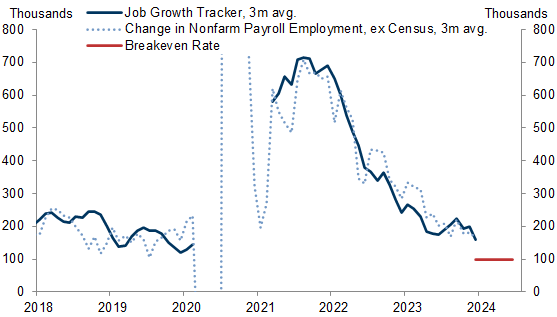

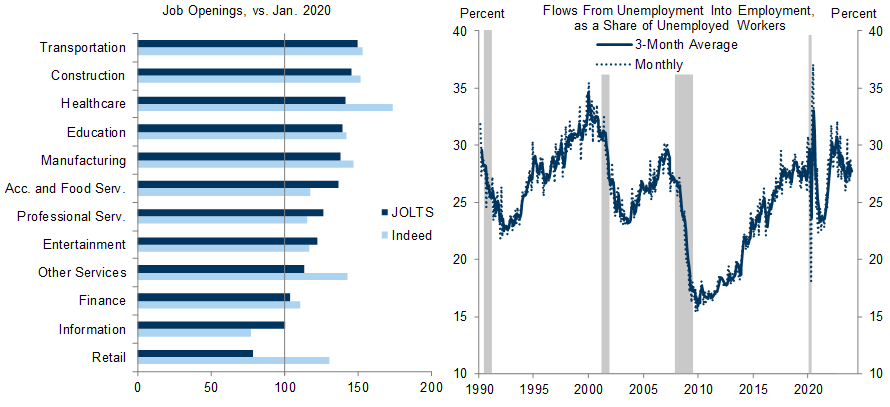

Risk 3: A sharper deterioration in the labor market is unlikely with job openings still high and the layoff rate still very low. While a few recent data points have been weaker, more statistically reliable signals such as trend payroll growth and our composite job growth tracker remain strong.

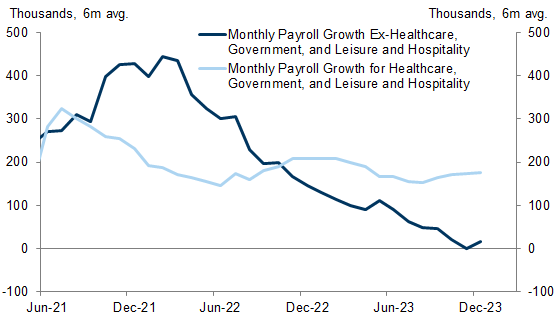

Risk 4: The narrow breadth of job growth is not indicative of either a mismatch problem or weak labor demand in most sectors—job openings are high in nearly all sectors—and it should normalize as hiring rebounds in industries that are particularly sensitive to financial conditions.

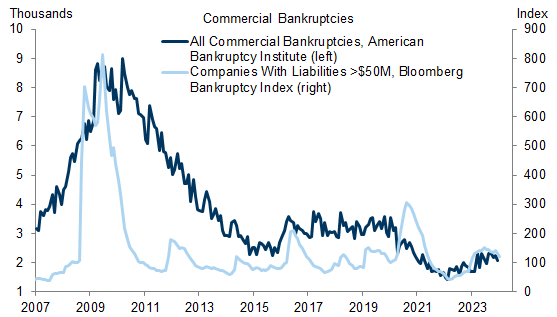

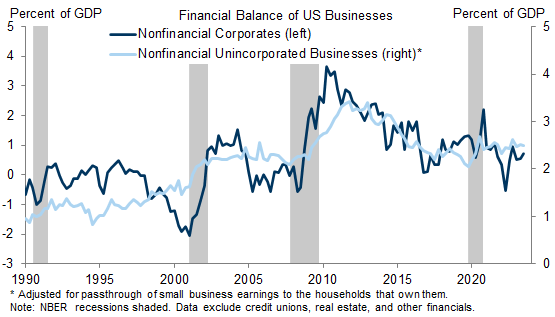

Risk 5: Rising corporate bankruptcies look less ominous and indeed quite low when compared to pre-pandemic levels. More broadly, the business sector remains on a solid financial footing.

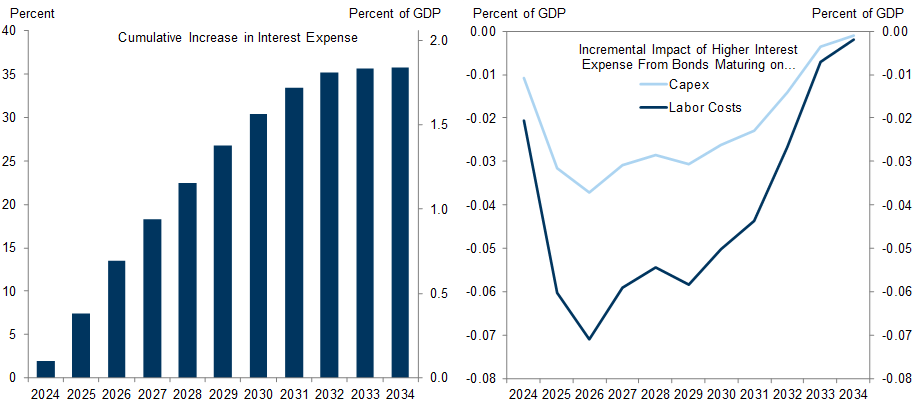

Risk 6: The corporate debt maturity wall will raise corporate interest expense with a longer delay than usual, but the resulting hit to capital spending and hiring is likely to be quite modest.

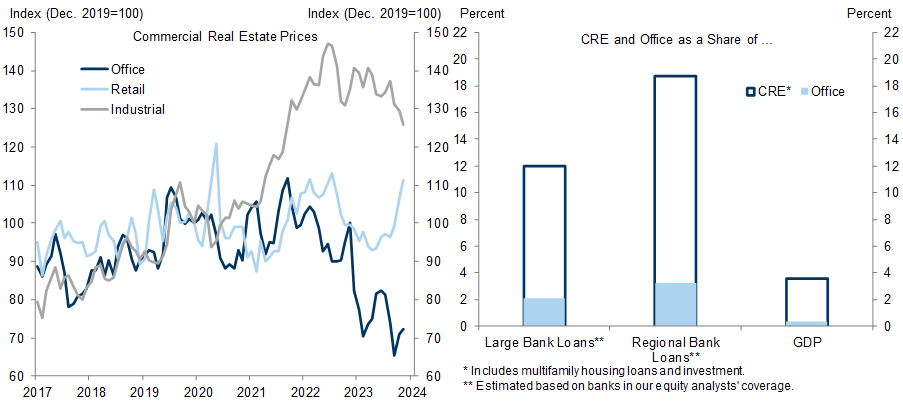

Risk 7: Commercial real estate broadly is not a problem, office specifically is. But office loans account for only 2-3% of banks’ loan portfolios, small enough for banks to manage the hit.

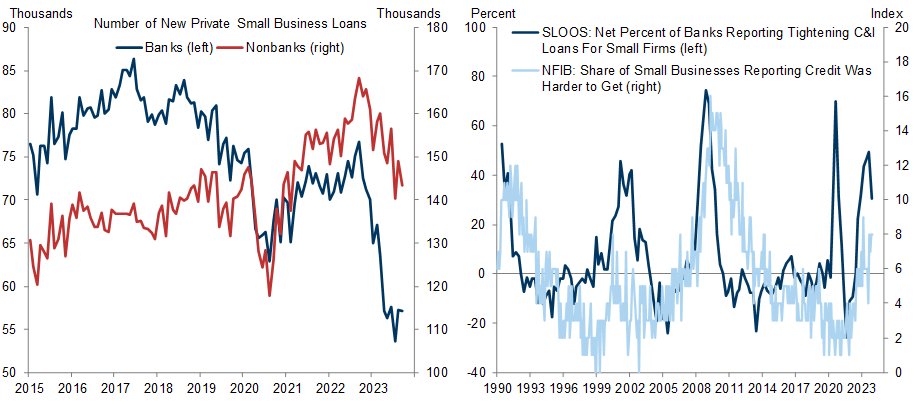

Risk 8: A bank credit crunch was a valid concern last spring, but the banking stress has not been as serious as feared, non-bank lenders cut back on lending by less, small businesses have not reported a severe lack of access to credit, and financial conditions have now eased meaningfully.

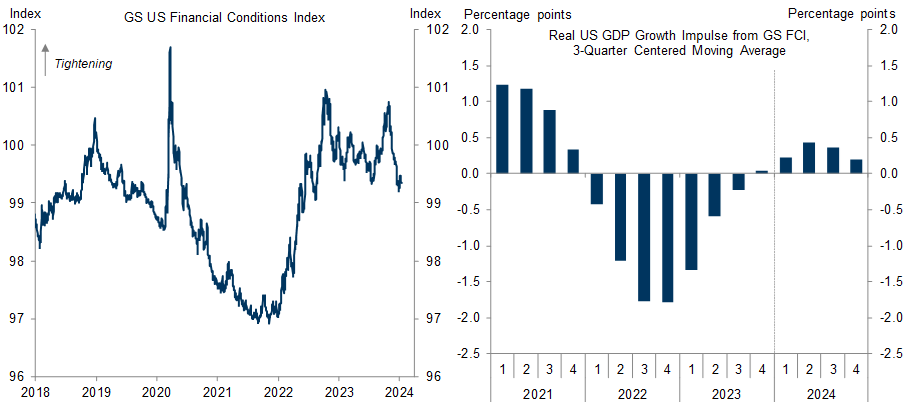

Risk 9: Something finally “breaking” due to higher interest rates is unlikely at this point because the peak growth hit from higher rates and tighter financial conditions is well behind us. Moreover, with inflation lower, the FOMC is at liberty to cut the funds rate more aggressively if necessary.

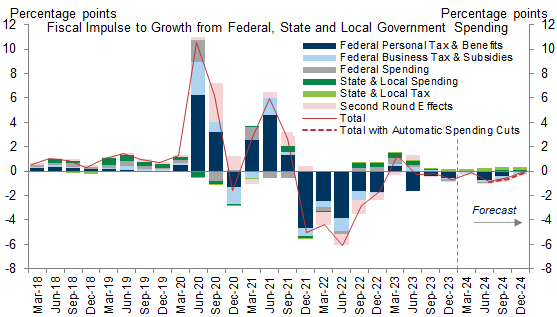

Risk 10: Fading fiscal support is less real than it appears—the federal deficit widened last year for reasons that were not very stimulative, and the fiscal impulse to GDP is likely to remain roughly steady this year, with a bit of downside risk from potential automatic spending cuts.

10 Growth Risks for 2024 and Why We Worry Less

Risk 1: A consumer slowdown if unsustainable spending ends, the saving rate rises from a low level, or households run out of excess savings

Risk 2: Rising consumer delinquency and default rates

Risk 3: A sharper deterioration in the labor market

Risk 4: The narrow breadth of job growth

Risk 5: Rising corporate bankruptcies

Risk 6: The corporate debt maturity wall

Risk 7: Commercial real estate

Risk 8: A bank credit crunch

Exhibit 14: Nonbanks Cut Back on Lending By Only Half As Much as Banks, Which Helps to Explain Why Small Businesses Have Not Reported a Lack of Access to Credit Despite Tighter Bank Lending Standards

Risk 9: Something finally “breaking” under higher interest rates if the Fed cuts too late

Risk 10: Fading fiscal support after a large widening of the federal deficit in 2023

David Mericle

Manuel Abecasis

Investors should consider this report as only a single factor in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html.